Local Lawyers Think 'Gross Negligence' Explains an Unlawful Murder Charge Based on a 'Self-Induced Abortion'

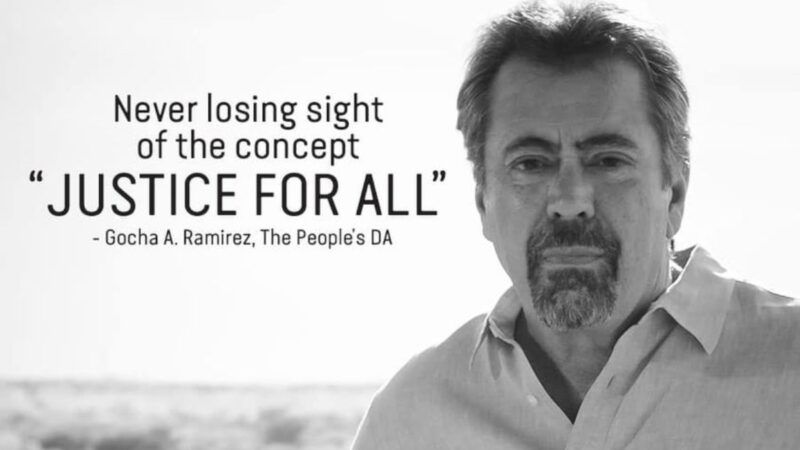

Starr County District Attorney Gocha Allen Ramirez has yet to explain how this egregious error escaped his notice.

Ignorance and incompetence, as opposed to pro-life convictions, seem to be the most likely explanations for why Starr County, Texas, prosecutors pursued a legally invalid murder charge against a woman for "a self-induced abortion." A local lawyer interviewed by The Washington Post said the consensus in the legal community is that the decision was the result of "gross negligence."

Ross Barrera, a former chairman of the Starr County Republican Party, described District Attorney Gocha Allen Ramirez as "a hardcore Democrat" who simply misunderstood the law. "I think his office just failed in doing their work," Barrera said. "I would put my hand on the Bible and say this was not a political statement."

Willfully ignoring the law to indict, arrest, and jail a young woman who clearly had committed no crime would be an outrageous abuse of power. But not knowing the law and not bothering to look it up before putting her through that ordeal amount to an egregious failure that should disqualify Ramirez from continuing to serve in an office that gives him broad authority to bring charges that can send people to prison—in this case, potentially for life.

Lizelle Herrera, the 26-year-old victim of Ramirez's astonishing carelessness, was treated at a hospital during a miscarriage in January. Rockie Gonzalez, founder of the abortion rights group La Frontera Fund, said Herrera "allegedly confided to hospital staff that she had attempted to induce her own abortion, and she was reported to the authorities by hospital administration or staff."

Even though it should have been clear from the outset that the allegation against Herrera was not a crime under Texas law, the Starr County Sheriff's Office referred the matter to Ramirez's office, which obtained a March 30 indictment that said Herrera "intentionally and knowingly cause[d] the death of an individual" on or about January 7 "by a self-induced abortion." Herrera was arrested last Thursday and spent two nights in jail before she was released after posting a $500,000 bond.

All of this was completely unlawful, as Ramirez conceded in a press release on Sunday. After "reviewing applicable Texas law," he decided to "immediately dismiss the indictment against Ms. Herrera," because "it is clear that Ms. Herrera cannot and should not be prosecuted for the allegation against her." The Texas Penal Code explicitly says a murder charge "does not apply to the death of an unborn child if the conduct charged is…conduct committed by the mother of the unborn child."

It remains unclear who in Ramirez's office sought the indictment against Herrera. The Post says "court officials referred questions about which prosecutor presented Herrera's case to the grand jury to Ramirez," who "could not be reached Wednesday morning." I emailed Ramirez and left a message for him, and I will update this post if I hear back from him.

The Post notes that one of the five prosecutors in Ramirez's office, Judith Solis, is the same lawyer who filed a divorce petition for Herrera's estranged husband on April 7, the day Herrera was arrested. "Melisandra Mendoza, a lawyer who used to work in the district attorney's office, said if Solis does not make Herrera's arrest an issue in the divorce, there may not be a conflict of interests," the Post says. But while local prosecutors are allowed to handle private civil cases, "she said she would not have taken the divorce case."

Herrera and her husband, who were married in 2015 and have two children, separated less than a week before her hospital visit, which suggests her decision regarding her pregnancy may have had something to do with it. "Listen, right now, I have no words," he told a local TV reporter. "It was a son. A boy."

Whether it was Solis or a different prosecutor who sought the indictment, that person clearly failed to meet the most basic requirement of such a decision: verifying that a suspect's alleged conduct satisfies the elements of the contemplated charge. Ramirez likewise displayed either a shocking indifference to the law (assuming that he approved the decision in advance) or lax supervision (assuming that he heard about the seemingly groundbreaking charge only afterward). The fact that it took a week and a half for Ramirez to discover his office's "gross negligence," and then only in response to the storm of criticism that Herrera's arrest provoked, does not reflect well on his attentiveness or his legal acumen.

In an interview with Nexstar Media Group, Southern Methodist University law professor Joanna Grossman "hypothesized" that the decision to charge Herrera with murder "could have been an error" based on "a misunderstanding" of S.B. 8, a.k.a. the Texas Heartbeat Act, which authorizes "any person" (except for government officials) to sue "any person" who performs or facilitates an abortion after fetal cardiac activity can be detected (typically around six weeks into a pregnancy). If Grossman is right, Ramirez (or an unsupervised underling) was remarkably ignorant.

S.B. 8, which took effect last September, explicitly says it does not authorize lawsuits against women who obtain prohibited abortions. Furthermore, the law does not authorize criminal prosecution of anyone, and it certainly does not amend the state's definition of criminal homicide. Both of those points were emphasized again and again in seven months of debate and litigation over S.B. 8. Nexstar reports that Ramirez's office "said it would not be providing any more commentary about the situation"—presumably to avoid further embarrassment.

As the Post notes, "even staunch antiabortion activists" condemned Herrera's arrest. "The Texas Heartbeat Act and other pro-life policies in the state clearly prohibit criminal charges for pregnant women," said John Seago, Texas Right to Life's legislative director. "Texas Right to Life opposes public prosecutors going outside of the bounds of Texas' prudent and carefully crafted policies."

The Post reports that Ramirez called Herrera's lawyer on Saturday, two days after her arrest and 10 days after the indictment, to admit that the murder charge had been a grave error. "I'm so sorry," Ramirez wrote in a text message to "an acquaintance" the next day. "I assure you I never meant to hurt this young lady."

That apology is open to interpretation: Did Ramirez mean that he did not approve the baseless murder charge or that he did not realize it would "hurt this young lady"? The latter possibility seems utterly implausible, but so does the series of unconscionable actions or inactions that put Herrera in jail: by the hospital, by the sheriff's office, by the prosecutor who presented the charge, by the grand jurors, and, most of all, by Ramirez himself.

Show Comments (24)