The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

How Narrow is the Pathway the Supreme Court Left for Suits Challenging SB 8 and Other Similar State Laws?

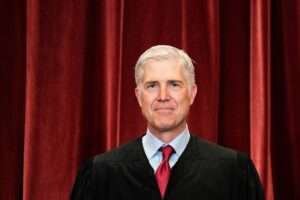

Things are far from completely clear. But Justice Gorsuch's opinion may give preenforcement challenges to SB 8 and other similar laws a good deal more wiggle room than many think.

As noted in my last post about today's Supreme Court ruling in in Whole Woman's Health v. Jackson, the key question for the future is how close a connection state officials must have to enforcement of the law in question before plaintiffs can potentially bring preenforcement challenges against those officials.

The Supreme Court allowed the anti-SB 8 lawsuits to go forward against Texas medical licensing board officials, but barred them from proceeding against state judges and the state Attorney General. Jonathan Adler describes this as a "slim pathway." Josh Blackman suggests it may be even more narrow than that, and concludes that abortion clinics in Texas probably could not reopen, even if they prevail.

I think Justice Gorsuch's opinion may well create more leeway for anti-SB 8 plaintiffs than these commentators suggest. As Gorsuch explains, the medical-licensing officials are subject to preenforcement lawsuits because "[e]ach of these individuals is an executive licensing official who may or must take enforcement actions against the petitioners if they violate the terms of Texas's Health and Safety Code, including S. B. 8."

Specifically, he points out that they can enforce SB 8 as follows:

Texas Occupational Code §164.055, titled "Prohibited Acts Regarding Abortion." That provision states that the Texas Medical Board "shall take an appropriate disciplinary action against a physician who violates . . . Chapter 171, Health and Safety Code," a part of Texas statutory law that includes S. B. 8. Accordingly, it appears Texas law imposes on the licensing-official defendants a duty to enforce a law that "regulate[s] or prohibit[s] abortion…"

Section 164.055 does not actually impose any criminal or civil liability against violators. Instead, it merely instructs the Texas Medical Board to "take an appropriate disciplinary action against a physician who violates Section 170.002 (Prohibited Acts; Exemption) or Chapter 171 (Abortion), Health and Safety Code. The board shall refuse to admit to examination or refuse to issue a license or renewal license to a person who violates that section or chapter."

The only harm the medical providers are likely to suffer is loss of an opportunity to apply for a license or license renewal. While Section 164.055 appears to require the Board take disciplinary action, Justice Gorsuch's opinion suggests that such a mandate isn't necessary to allow preenforcement lawsuits. It is enough that the defendants be officials who "may or must" take enforcement action (emphasis added).

As discussed in my earlier post, in the modern regulatory state there is a vast array of state and local officials and regulatory bodies who can potentially deny permits, licenses, or regulatory approvals to people and organizations based on all sorts of possible violations of law. Think of examples like zoning boards, licensing boards, land-use regulators, and many, many others. To be sure, Justice Gorsuch notes that would-be plaintiffs must face a "credible threat" of enforcement action. But that doesn't necessarily mean there must be a high likelihood of such enforcement. Even, say, a 5% chance might be a credible threat, especially in a context where the consequences of such an action might be severe (as in the loss or suspension of a valuable license).

It is also possible that Gorsuch's reasoning permits preenforcement lawsuits against officials against officials charged with enforcing state-court judgments after the fact. Examples include sheriffs and other similar law-enforcement officials. Recall that Gorsuch's reason for rejecting the idea of suing state court clerks is that clerks "serve to file cases as they arrive, not to participate as adversaries in those disputes." Like judges, they are supposed to impartially deal with cases, not help one side or the other.

But that obviously isn't true of sheriffs and other officials who enforcement judgments after a case is over. Their duty is to enforce rulings in favor of the winning side. And doing so is necessarily "adverse" to the interests of the losers. There are no sheriff or other similar defendants in the current SB 8 case. But abortion providers might be able to bring lawsuits against them in the future. And the same goes for lawsuits against law-enforcement officials tasked with enforcing judgements under future laws imitating SB 8.

Admittedly, it's possible to set out a more limited interpretation of Gorsuch's opinion than the one set out above. The range of officials subject to preenforcement lawsuits under his logic is far from completely clear. These issues are likely to be litigated in future cases - both additional challenges to SB 8 and (potentially) challenges to imitation statutes enacted in the future.

One possible reason why Gorsuch's opinion is so frustratingly unclear about the scope of potential lawsuits that it authorizes against government officials is that it may be a compromise between the four justices who signed on to it: Alito, Barrett, Kavanaugh, and Gorsuch himself. The oral argument revealed that Barrett and - especially - Kavanaugh have strong concerns about the dangerous precedent SB 8 could set for laws targeting other constitutional rights. Alito and Gorsuch may be less worried. In a future case raising similar issues, the four-justice bloc might splinter. If so, it would only take one "defector" to form a five-person majority in favor of broad preenforcement litigation rights, along with the four dissenting justices in Whole Woman's Health.

Even if targets of SB 8-style laws can bring cases against a variety of government officials, the resulting rulings might lead only to injunctions against those officials, not the private "bounty hunter" litigants authorized to sue people under SB 8 and its potential imitations. But successful lawsuits against government officials can create federal-court precedents that are binding on private litigants, as well. Federal district court decisions are not binding precedents (though they can serve as "persuasive" authority). But those of the courts of appeals are. They bind not only lower federal courts, but also state courts within their areas of jurisdiction [but see update on this below]. And cases addressing important constitutional issues are highly likely to lead to appellate rulings.

In sum, depending on how it is interpreted, Justice Gorsuch's opinion in today's SB 8 case could potentially allow broad opportunities for preenforcement actions against both SB 8 itself, and potential future imitations. But we can't know for sure until a good deal of additional litigation has occurred - perhaps even another Supreme Court case.

One of the main functions of Supreme Court decisions is to set down clear rules for lower courts to follow in future cases. By that standard, today's decision falls short. It creates far more uncertainty than it resolves. But that uncertainty could yet be resolved in ways that preclude further SB 8-style subversions of judicial review.

UPDATE: I should note that there is much more doubt about the binding nature of federal appellate court precedents on state courts than I initially suggested. While some state courts routinely follow them, others - including those of Texas - do not, and treat them only as persuasive authority. To my mind, the latter practice is at odds with longstanding Supreme Court precedent on the supremacy of federal courts in interpreting federal law, such as Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816). But the issue is much more contestable than I had previously assumed. For more detail, see this 2015 article on the subject by Amanda Frost.

Show Comments (37)