The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

How Narrow is the Pathway the Supreme Court Left for Suits Challenging SB 8 and Other Similar State Laws?

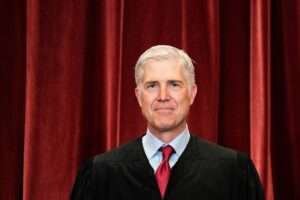

Things are far from completely clear. But Justice Gorsuch's opinion may give preenforcement challenges to SB 8 and other similar laws a good deal more wiggle room than many think.

As noted in my last post about today's Supreme Court ruling in in Whole Woman's Health v. Jackson, the key question for the future is how close a connection state officials must have to enforcement of the law in question before plaintiffs can potentially bring preenforcement challenges against those officials.

The Supreme Court allowed the anti-SB 8 lawsuits to go forward against Texas medical licensing board officials, but barred them from proceeding against state judges and the state Attorney General. Jonathan Adler describes this as a "slim pathway." Josh Blackman suggests it may be even more narrow than that, and concludes that abortion clinics in Texas probably could not reopen, even if they prevail.

I think Justice Gorsuch's opinion may well create more leeway for anti-SB 8 plaintiffs than these commentators suggest. As Gorsuch explains, the medical-licensing officials are subject to preenforcement lawsuits because "[e]ach of these individuals is an executive licensing official who may or must take enforcement actions against the petitioners if they violate the terms of Texas's Health and Safety Code, including S. B. 8."

Specifically, he points out that they can enforce SB 8 as follows:

Texas Occupational Code §164.055, titled "Prohibited Acts Regarding Abortion." That provision states that the Texas Medical Board "shall take an appropriate disciplinary action against a physician who violates . . . Chapter 171, Health and Safety Code," a part of Texas statutory law that includes S. B. 8. Accordingly, it appears Texas law imposes on the licensing-official defendants a duty to enforce a law that "regulate[s] or prohibit[s] abortion…"

Section 164.055 does not actually impose any criminal or civil liability against violators. Instead, it merely instructs the Texas Medical Board to "take an appropriate disciplinary action against a physician who violates Section 170.002 (Prohibited Acts; Exemption) or Chapter 171 (Abortion), Health and Safety Code. The board shall refuse to admit to examination or refuse to issue a license or renewal license to a person who violates that section or chapter."

The only harm the medical providers are likely to suffer is loss of an opportunity to apply for a license or license renewal. While Section 164.055 appears to require the Board take disciplinary action, Justice Gorsuch's opinion suggests that such a mandate isn't necessary to allow preenforcement lawsuits. It is enough that the defendants be officials who "may or must" take enforcement action (emphasis added).

As discussed in my earlier post, in the modern regulatory state there is a vast array of state and local officials and regulatory bodies who can potentially deny permits, licenses, or regulatory approvals to people and organizations based on all sorts of possible violations of law. Think of examples like zoning boards, licensing boards, land-use regulators, and many, many others. To be sure, Justice Gorsuch notes that would-be plaintiffs must face a "credible threat" of enforcement action. But that doesn't necessarily mean there must be a high likelihood of such enforcement. Even, say, a 5% chance might be a credible threat, especially in a context where the consequences of such an action might be severe (as in the loss or suspension of a valuable license).

It is also possible that Gorsuch's reasoning permits preenforcement lawsuits against officials against officials charged with enforcing state-court judgments after the fact. Examples include sheriffs and other similar law-enforcement officials. Recall that Gorsuch's reason for rejecting the idea of suing state court clerks is that clerks "serve to file cases as they arrive, not to participate as adversaries in those disputes." Like judges, they are supposed to impartially deal with cases, not help one side or the other.

But that obviously isn't true of sheriffs and other officials who enforcement judgments after a case is over. Their duty is to enforce rulings in favor of the winning side. And doing so is necessarily "adverse" to the interests of the losers. There are no sheriff or other similar defendants in the current SB 8 case. But abortion providers might be able to bring lawsuits against them in the future. And the same goes for lawsuits against law-enforcement officials tasked with enforcing judgements under future laws imitating SB 8.

Admittedly, it's possible to set out a more limited interpretation of Gorsuch's opinion than the one set out above. The range of officials subject to preenforcement lawsuits under his logic is far from completely clear. These issues are likely to be litigated in future cases - both additional challenges to SB 8 and (potentially) challenges to imitation statutes enacted in the future.

One possible reason why Gorsuch's opinion is so frustratingly unclear about the scope of potential lawsuits that it authorizes against government officials is that it may be a compromise between the four justices who signed on to it: Alito, Barrett, Kavanaugh, and Gorsuch himself. The oral argument revealed that Barrett and - especially - Kavanaugh have strong concerns about the dangerous precedent SB 8 could set for laws targeting other constitutional rights. Alito and Gorsuch may be less worried. In a future case raising similar issues, the four-justice bloc might splinter. If so, it would only take one "defector" to form a five-person majority in favor of broad preenforcement litigation rights, along with the four dissenting justices in Whole Woman's Health.

Even if targets of SB 8-style laws can bring cases against a variety of government officials, the resulting rulings might lead only to injunctions against those officials, not the private "bounty hunter" litigants authorized to sue people under SB 8 and its potential imitations. But successful lawsuits against government officials can create federal-court precedents that are binding on private litigants, as well. Federal district court decisions are not binding precedents (though they can serve as "persuasive" authority). But those of the courts of appeals are. They bind not only lower federal courts, but also state courts within their areas of jurisdiction [but see update on this below]. And cases addressing important constitutional issues are highly likely to lead to appellate rulings.

In sum, depending on how it is interpreted, Justice Gorsuch's opinion in today's SB 8 case could potentially allow broad opportunities for preenforcement actions against both SB 8 itself, and potential future imitations. But we can't know for sure until a good deal of additional litigation has occurred - perhaps even another Supreme Court case.

One of the main functions of Supreme Court decisions is to set down clear rules for lower courts to follow in future cases. By that standard, today's decision falls short. It creates far more uncertainty than it resolves. But that uncertainty could yet be resolved in ways that preclude further SB 8-style subversions of judicial review.

UPDATE: I should note that there is much more doubt about the binding nature of federal appellate court precedents on state courts than I initially suggested. While some state courts routinely follow them, others - including those of Texas - do not, and treat them only as persuasive authority. To my mind, the latter practice is at odds with longstanding Supreme Court precedent on the supremacy of federal courts in interpreting federal law, such as Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816). But the issue is much more contestable than I had previously assumed. For more detail, see this 2015 article on the subject by Amanda Frost.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

This is why the Supreme Court does not like to issue opinions before judgement.

Gorsuch's opinion is not clear because Texas law regarding the medical licensing board was not clear, at least to 5 Justices. They left it up the Texas courts first to decide what the law was-whether licensing board officials could enforce SB8.

But his opinion was very clear that the unconstitutionality of the law could be raised as a defense once providers were sued.

Providers have already been sued, but until an abortion made illegal by SB8 but declared a constitutional right by Casey takes place the plaintiffs ought not prevail. I'm not seeing how you get such a case.

The Fifth Circuit could certify to the high court of Texas the question of whether the named officials have any authority. That would preserve the status quo for a few months, which I assume to be a mostly acceptable outcome in the court.

Another meek SC decision to avoid the hard work of making a wise decision.

The justices are so afraid to clearly delineate an opinion, it’s really pathetic.

They may perceive themselves to be in a tough spot, attempting to appease old-timey right-wingers without provoking better Americans to enlarge the Supreme Court and relegate the Republicans to careers of writing seething, bitter, inconsequential dissents. Perhaps at least some of these educated, experienced conservatives have had enough of getting stomped by the liberal-libertarian mainstream and want to try to avoid more ideological pain.

I look forward to the Rev pontificating about how there is twenty years of tradition behind the 15 member SCOTUS and these bomb throwing Republicans are just trying to overturn the Constitution with their proposals to add judges.

In 20 years, better Americans will have stomped movement conservatives into thorough irrelevance in modern politics. Republicans scheduling the Federalist Society annual convention will be searching for a ballroom that doesn't impose a minimum charge.

Racism, childish superstition, attempted voter suppression, belligerent ignorance, can't-keep-up backwaters, and obsolete thinking will have severe consequences. As they should.

All this learned analysis, by Somin and others, misses the forest fro the trees.

A majority of the Justices are anti-abortion, and will make any remotely plausible ruling that helps restrict the right. That's what's going on - no more, no less - regardless of what a lot of law professors say about it.

Should it matter if you are anti-abortion or pro-abortion if Roe vs Wade is bad law and not supported by the text or history of the Constitution?

In theory it shouldn't. I think some people are actually pretty good at clearly separating their preferred outcome from their objective legal analysis. At least a couple of the bloggers on this site seem to do it quite well. Maybe that's at least in part because they have less at stake with their analysis than SC judges.

I really try not to be cynical but I think it's difficult to dismiss as mere coincidence the fact that the judges who think Roe was a bad decision are also personally pro life, while those who feel like Roe was the most reasonable of constitutional interpretations happen to be pro choice. Their respective positions on Roe also don't totally square with some of their other decisions that deal with potentially implied constitutional liberties.

Perhaps some judges more than others are less shy about how IMPORTANT they feel a certain right is. I can't say that passes for objective constitutional interpretation, but at least it's honest.

All that said, I tend to be less cynical than bernard on this one. I don't think any of the justices are big fans of clever constitutional workarounds, especially the conservative judges. They already know how Dobbs is going to go. If they want to overturn Roe it's a done deal. They don't need to mince about with SB 8 to prevent abortions. I have to assume they aren't all going full Sotomayor on this case due at least somewhat principled, rather than preferred outcome reasons.

This is exactly what is going on. SCOTUS has gone off the tracks with the Trump appointees. I used to have some respect for the conservatives other than Thomas, he's always been a loser. Roberts is a decent guy. The 3 Trump appointments are all theofascist hacks.

“[Federal courts-of-appeals opinions] bind not only lower federal courts, but also state courts within their areas of jurisdiction.”

That’s not true. The 5th Circuit itself—in which Texas is located—has recognized that state courts and federal courts of appeals can reach contrary conclusions about federal law (including federal constitutional law), which would create a split of authority for SCOTUS to review and reconcile (if it chose to). See, e.g., Magouirk v. Phillips, 144 F.3d 348, 361 (5th Cir. 1998) (state courts located in the Fifth Circuit “are not bound by Fifth Circuit precedent when making a determination of federal law”); see also Penrod Drilling Corp. v. Williams, 868 S.W.2d 294, 296 (Tex. 1993) (“While Texas courts may certainly draw upon the precedents of the Fifth Circuit, or any other federal or state court, in determining the appropriate federal rule of decision, they are obligated to follow only higher Texas courts and the United States Supreme Court.”).

Just to be clear, is Ilya saying that this decision implies that a pre-judgement decision to prevent law enforcement from forcing the loser of an SB-8 lawsuit to actually pay would fly?

Did the plaintiffs in this case just totally drop the ball in not listing such cops as defendants? Do they get another crack at it with this new useful information? Or could it only apply to future similar laws?

Since when are the police in the business of debt collecting on private civil judgements?

No Ilya's not saying that and no, the plaintiffs didn't drop the ball on that.

Perhaps I totally misinterpreted this:

"But that obviously isn't true of sheriffs and other officials who enforcement judgments after a case is over. Their duty is to enforce rulings in favor of the winning side. And doing so is necessarily "adverse" to the interests of the losers. There are no sheriff or other similar defendants in the current SB 8 case. But abortion providers might be able to bring lawsuits against them in the future. And the same goes for lawsuits against law-enforcement officials tasked with enforcing judgements under future laws imitating SB 8."

He does seem to be saying that law enforcement officials are tasked with enforcing judgements under SB 8 type laws. If this duty doesn't fall to some kind of law enforcement official, who does enforce it? I assume someone has to do something to enforce the judgment if the loser of a lawsuit refuses to pay.

Some abortions are not protected by Casey, and therefor some plaintiffs will be entitled to collect judgments against some abortionists. But if the abortion is protected by Casey the courts ought not, under SB8, decide in favor of the plaintiff, so there ought be no such judgments to collect. This has utterly failed to register in the rotten walnut Somin uses for a brain.

Doesn't SB 8 defy Casey by moving the deadline to the detection of a fetal heartbeat? I agree that if the abortion is protected by Casey then the courts ought not to decide in favor of the plaintiff. But why wouldn't they if SB 8, as currently written, is allowed to stand?

But that really has little to do with my question. I did a quick google search about how civil judgements are enforced in Texas, and it seems that there are multiple ways. But ultimately there is a path where property is physically seized by a Sheriff or Marshal. Perhaps a pre-judgement decision could be made against them.

What Gandydancer doesn't understand and has never understood is that SB8 does two separate things: (1) it makes an abortion illegal after roughly six weeks; and (2) it authorizes these bounty-hunting lawsuits against anyone (other than the pregnant woman) who facilitates an abortion after roughly six weeks. While the former is clearly not enforceable as long as Casey is still good law, the same cannot be said for the latter.

A woman in Texas who has been pregnant for 15 weeks asks you to help her pay for an abortion. You do. Someone decides to sue you under SB8. You cannot assert Casey as a defense under SB8; you lose.

A receptionist at an abortion clinic gets sued after a woman has an abortion at 15 weeks. Someone decides to sue the receptionist. The receptionist cannot assert Casey as a defense under SB8. The receptionist loses.

A doctor at an abortion clinic gets sued after a woman has an abortion at 15 weeks. Someone decides to sue the doctor. The doctor might be able to assert Casey as a defense, but maybe not. A state judge could easily rule otherwise, given the constraints SB8 imposes on the judge's discretion.

But that obviously isn't true of sheriffs and other officials who enforcement judgments after a case is over. Their duty is to enforce rulings in favor of the winning side. And doing so is necessarily "adverse" to the interests of the losers. There are no sheriff or other similar defendants in the current SB 8 case. But abortion providers might be able to bring lawsuits against them in the future. And the same goes for lawsuits against law-enforcement officials tasked with enforcing judgements under future laws imitating SB 8.

Yes, a defendant who loses an SB 8 case in state court could attempt all these novel approaches to civil procedure and run to the federal courthouse to seek injunctions against sheriffs and constables and anyone else who might enforce the state judgment.... OR - here's a crazy idea - he could appeal to the state's intermediate court. And, if necessary, to the state supreme court. And, ultimately to SCOTUS.

Our clerisy seems to believe that review in state courts is not "real" judicial review, which can only be found in the Solomonesque wisdom inherent in all federal judges, while state judges are all semi-literate hayseeds holding court in their saloons.

Not all judges are semi-literate hayseeds. Only the judges in states controlled by Republicans are bigoted, gape-jawed, superstitious hayseeds.

Yes, but you're talking about a defendant who actually loses an SB 8 case, I assume because the defendant did in fact violate that law. There are certainly paths open to potential victory, but it's obviously more of a risk than getting a pre-judgement against enforcement, which is all that section of the article is about.

TO DO OR NOT TO DO & DISAVOWAL OF INTENT TO DO

RE: "Josh Blackman suggests it may be even more narrow than that, and concludes that abortion clinics in Texas probably could not reopen."

Since this is a learned blog and semantics count, I would object the interchangeable use of "can" and "may". You can do a lot of things, and the same goes for abortion clinics, whether lawful or otherwise. The question is not whether it's possible for them kto do abortions as a factual matter (can), but what the legal consequences might be (liability risk assessment) or will be (prediction). And whether to do or not to do is ultimately a question of choice. Also note that SB8 does not proscribe all abortions, but whether legal or not, it's still a choice. And it's also a choice (business decision for those in the abortion industry) to continue to perform no-heartbeat abortions, or cease doing so.

And since it is a question of choice, it can't really be predicted with certainty for specific actors, whether individuals or organizations. After all, the person or collective decisionmaking body in the position to do the chosing may chose contrary to the prediction, and circumstance may change affecting their risk/benefit calculus.

This is relevant to the SB8 litigation in multple ways, including the requests for injunctive relief against persons who are entitled to bring SB8 suit, but may chose not to do so, such as Mr. Dickson in the federal litigation and Mr. Seago in the 14 state preenforcement challenges that are currently subject to MDL treatment and therefore under the control of a single state judge.

I was suprised that the SCOTUS let Mr. Dickson in WWH v. Jackson off based on his disavowel of present intent to bring SB8 suits. How do they know he hasn't changed his mind about suing the abortionists in the interim? This would seem to be a fact issue for the trial court to take up at the preliminary injunction hearing that has never taken place because the defendants appealed the denial of their jurisdictional challenge (provided that there aren't other defenses that preclude injunctive relief against Dickson in federal court).

The same goes for the request for a permanent injunction against Texas Right to Life in the MDL cases in state court. Judge Peeples didn't resolve that on the conclusion that the matter involved contested facts and would therefore have to be taken up at trial (summary judgment not being available when material facts are disputed). But since SCOTUS has agreed to dismiss Dickson as a defendant, it would seem that the position of Texas Right to Life and Mr. Seago in favor of a similar dismissal in state court has been strenghtened. But there is a twist: An agreed temporary injunction is currently in place, pending final trial (or other type of disposition) and that is arguably enforceable under contract principles (Tex. R. Civ. P. 11) that don't depend on the trial court having jurisdiction to impose it on Texas Right to Life. So, even though Judge Peeples has denied TRTL's motion to dismiss asserting the absence of jurisdiction (called plea to the jurisdiction), it might yet turn out on appeal that the case against TRTL is not viable, at least not with respect to relief in the form of an anti-suit injunction. That would then leave only the declaratory judgments claims (already resolved by partial summary judgment). Regardless of the outcome regarding SB8 constitutionality, TRTL's right to access the courts and engage in other first amendment activity (association, sharing of abortion law information, fund raising, recruitment of sidewalk pro life counseling, etc.) would be preserved, but it would no longer make any sense for TRTL to bring SB8 lawsuits that are bound to fail under the declaratory judgment as to invalidity, if it is upheld on appeal (though that is iffy on at least some of the constitutional arguments raised in the summary judgment proceeding). Unless, of course, the purpose of a future lawsuit is to further develop the caselaw, or modify existing precedent, through a test case. Since a declaratory judgment by the Texas Supreme Court (on appeal from the MDL cases) could settle the law, requests for injunctive relief against enforcement may become moot because there would no basis to invoke the specter of a serious litigation threat and "massive" potential liablity.

"UPDATE: I should note that there is much more doubt about the binding nature of federal appellate court precedents on state courts than I initially suggested. While some state courts routinely follow them, others - including those of Texas - do not, and treat them only as persuasive authority."

Might this have to do with the fact that state supreme court decisions can be appealed directly to SCOTUS, but not to the federal circuit courts?

Given that, I can see a case for circuit court decisions being no more binding on state courts than they are on the other circuits.

As for Texas:

See In re Morgan Stanley & Co., 293 S.W.3d 182, 189-90 (Tex. 2009); Penrod Drilling Corp. v. Williams, 868 S.W.2d 294, 296 (Tex. 1993) ("While Texas courts may certainly draw upon the precedents of the Fifth Circuit, or any other federal or state court, in determining the appropriate federal rule of decision, they are obligated to follow only higher Texas courts and the United States Supreme Court.").

In other words, the SCOTX gets to decide what they find persuasive.

If so, it would only take one "defector" to form a five-person majority in favor of broad preenforcement litigation rights, along with the four dissenting justices in Whole Woman's Health.

I think this is right, but I have a more cynical take on it. I think the point of the Gorsuch opinion was to ensure that no constitutional challenge actually stops SB8 from operating, while ensuring that there are sufficient levers that any SB8 on a liberal issue, such as gun control, could be stopped.

And by the way, this shows you how for all the crap he gets, CJ Roberts is actually more principled than the supposed originalists and textualists. Because he's actually willing to make rulings that further a constitutional right he doesn't like- abortion- in order to ensure the law doesn't go in a bad direction.

One of the biggest lies in all of legal theory is the claim of originalists and textualists that they are governed by principle. No, actually, the people they stand against are far more likely to be governed by principle.

Professor Somin may be right in surmising that the opinion of the court represents a compromise between Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett on the one hand, and Alito and Gorsuch on the other, and that although the opinion as written focuses on peculiarities of Texas law creating loopholes in the no-state-enforcement provisions, Kavanaugh and Barrett might take a more expansive view if Texas or another state were to pass a tighter law with these sorts of loopholes closed.

I am not so sure. I would personally prefer it if this were the case. I think that a state cannot create a law that simultaneously violates well-established precedent on constitutional rights, insulates enforcement from federal courts, and stacks state court procedings against defendants in a way that makes the process of litigation as onorous as possible even if defendants ultimately prevail. I think the findamentaal position underlying Cooper v. Aaron was correct - states cannot create a structure specifically designed to take away established constitutional rights and expect to get away with it. Its opposite, United States v. Cruikshank, essentially gave states free license to create a near slave system notwithstanding the Civil War amendments by privatizing the enforcement system. Under Cruikshank, if the sherriff and posse simply took off their badges before conducting the lynching, the state was not responsible, everything done was private, and hence no federal civil rights were violated. That cannot be allowed to happen again.

I agree it was a completely reasonable strategy to first look for loopholes in the law and exploit them if available before considering more drastic strategies. I also agree it was correct not to make more drastic strategies available if less drastic ones would so the job. However, I would not have foreclosed more drastic strategies as the opinion appeared to have done. I agree the state’s judiciary is inconsistent with Ex Parte Young and also not a genuinely adversary party. But I would simply not haave decided on the Attorney General and left that question for another day.

Perhaps Professor Somin is right that state regulatory strategies inevitably leave these sorts of loopholes open. And perhaps he is also right that it is not as easy as it might seem for a really determined legislature to find a way to close them.

But I am not so sure.

The opinion seemed to focus on a very specific loophole in Texas law, that a differenct section gave the Trcas Medical Board authority to enforce “this chapter,” a chapter that included SB8, thereby creating a back door into enforcement of SB8. It’s a back door that would seem rather easy to close, simply by amending “this chapter” to add “except…” That’s why I had characterized omitting closure of this back door as a mere screwup on the Texas Legislature’s part, something they could fix with a simple amendment.

Professor Somin may be right that a wider variety of state officials have at least an indirect role in enforcing state laws and could potentially be found liable. I hesitate at the consequences of casting the net really low. If letter-carriers can be found liable for delivering mail containing prohibited process, wouldnt they at least be permitted, if not required, to open everybody’s mail to see if it contains something that imposes liability on them if delivered? That mighht be a net loss to people’s liberties. And of course states could develop electronic process (and take advantage of private internet providers and Section 230) to cover this.

If one has to create a new expanision of or exception to Ex Parte Young, it might do less collateral damage to do it at the top rather than at the bottom. That is why I saw the Court’s apparent foreclosing of this option as a problem.

And to clarify, the top of the Executive Branch. I think there is a certain fundamental unfairness in making low level officials like letter-carriers involved in court functions personally responsible for the contents of the dispute they are peripherally involved in. This fundamental unfairness wouldn’t exist for people like the Governor, who come to think of it wasn’t named and hence wasn’t passed on in this suit.

This judgement is a joke. The entirety of Texas SB8 makes a mockery of the constitution and the scotus. Thus by extension it also is a mockery of Gorsuch's opinion. Lol what a bunch of losers we have in the SCOTUS

It is also possible that Gorsuch's reasoning permits preenforcement lawsuits against officials against officials charged with enforcing state-court judgments after the fact. Examples include sheriffs and other similar law-enforcement officials. Recall that Gorsuch's reason for rejecting the idea of suing state court clerks is that clerks "serve to file cases as they arrive, not to participate as adversaries in those disputes." Like judges, they are supposed to impartially deal with cases, not help one side or the other.

But that obviously isn't true of sheriffs and other officials who enforcement judgments after a case is over.

Bzzt. Thank you for playing, but no. The sheriff isn't party to the case. The sheriff is impartial to the people. the sheriff is simply enforcing an order from an impratial judge.

For the sheriff to be "partial", then the judge who rules against a party is equally "partial"

This one was stupid, even for you.

In a future case raising similar issues, the four-justice bloc might splinter. If so, it would only take one "defector" to form a five-person majority in favor of broad preenforcement litigation rights, along with the four dissenting justices in Whole Woman's Health.

Oh, please. There's not the slightest chance that Kagan, Breyer, or Sotomayor would provide the 5th vote for a preenforcement challenge against a CA version of SB 8 that was aimed at gun owners.

Exactly how stupid do you think we are?

I bet you a hundred dollars to ylur nickel that at least Breyer or Kagan would gladly allow pre-enforcement challenges to similarly structured gun laws if it would allow similar pre-enforcment challenges to similarly structured abortion laws. It’s a mistake to characterize those who dissagree with you on the substantive issue as completely lacking in logical consistency on evefy procedural issue.

I am quite sure that Breyer and Kagan would be happy to offer to pay us Tuesday for a hamburger given to them today

I am equally positive that they'd never pay up.

Compare their votes blocking Trump from terminating DACA, to their votes in favor of letting Biden nuke MPP

Observe the "Justices" unwilling to uphold Heller, yet who demand that Roe and Casey be upheld.

The Left in America is fundamentally dishonest, and utterly lacking in good faith.

Left wing judges and justices in America are entirely results oriented, which is to say they have no principles, and no respect for anything but their personal political desires.

Disagree? Great. List the cases where left wing "justices" provided the deciding vote for a SCOTUS decision where the political Left lost. Since that's what you claim they'd be willing to do in this case

I don't think Greg really wants to hear the answer to that question.

Since you're the chump who fell for the CD KY study hoax press release headline, you're far too stupid for your opinions to matter

Are libel laws subject to pre-enforcement challenges in federal court?