The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

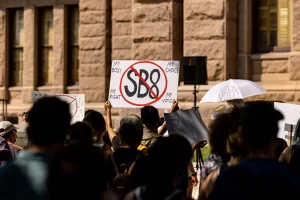

A (Belated) Final Word on Principles and Texas SB 8

A delayed, but hopefully still helpful final rejoinder to Stephen Sachs.

Last week, co-blogger Stephen Sachs posted a thoughtful response to my most recent critique of his position on the Texas SB 8 litigation. For earlier phases in this debate see my post arguing that a Supreme Court ruling in favor of Texas' SB 8 anti-abortion law creates greater slippery-slope risks than a ruling against it, and Steve's earlier post on the same topic, to which I was responding. In this post, I will make a brief final rejoinder. Steve is, of course, welcome to respond further, if he wishes to do so. I am sorry I took so long to respond, which occurred because I had other pressing commitments.

Throughout my commentary on SB 8, I have emphasized the danger that, if Texas' ploy works, it will create a blueprint for other states to undermine a variety of constitutional rights, including gun rights, property rights, free speech rights, and many others. For me and others with similar concerns, the SB 8 case is not primarily about abortion rights or the future of Roe v. Wade. The Supreme Court will soon enough have the opportunity to weigh in on those issues in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, a case where the state government did not attempt to evade judicial review. Rather, the main stake in the SB 8 case is whether Texas and other states - both red and blue - will be able to gut judicial review for a wide range of constitutional rights. In my previous posts, I outlined reasons why protecting judicial review should take priority over other considerations that might be at issue in the SB 8 litigation, and how this can be accomplished while minimizing disruption of existing precedent on sovereign immunity and limitations on federal court injunctions against state court judges (though I myself would be happy to see those precedents simply overruled).

In his latest post Steve, makes two additional points, which I will address in turn. First, this one:

I want to be clear that I'm not accusing Ilya of being unprincipled! In his view, the "silly and artificial" distinctions barring such suits aren't really part of the law, and a more general rights-protective principle is. I see this position as perfectly coherent, albeit mistaken. My argument is addressed to those who don't see such distinctions as silly and artificial, who don't see a general rights-protective principle as trumping ordinary procedural doctrines, etc. If one accepts that fed-courts doctrines routinely (and often for good reason) get in the way of plaintiffs who want to make constitutional arguments, and if one accepts that governments routinely structure their conduct with this in mind, then one shouldn't endorse a good-for-this-train-only exception here.

I appreciate Steve's comment on my commitment to principles! But my argument is not solely addressed to those whose views on these doctrines are the same as mine. It is also addressed to people who value existing precedent on sovereign immunity and federal injunctions against state courts, but also value the preservation of judicial review of state government policies targeting constitutional rights. In my previous contributions to our exchange, I explain why the latter commitment should take precedence over the former when the two conflict, and also why this need not lead to the complete reversal of previous precedent (though it would likely impose some limitations on it).

When two principles conflict, choosing the more important over the less important isn't unprincipled. Much the contrary. And it isn't "a good-for-this-train-only exception." The same prioritization applies in every other instance where similar conflicts between principles arise. Prioritizing greater principles over lesser ones is itself a a principled commitment; maybe even a meta-principle.

Steve's second point is the following:

We should distinguish between the source of a legal right and the source of the legal means for its enforcement. For example, we all have a legal right not to be kidnapped. If we bring an ordinary tort suit against our kidnappers, or if we raise this right as a defense in any custody suit the kidnappers bring, we ought to win. That's judicial review for you. But judicial review is a hopelessly ineffective means of enforcing this right; that's why we need legislatures to create police forces to track down kidnappers and arrest them. Likewise, the Fourteenth Amendment distinguishes our constitutional rights from the "appropriate legislation" we might need to "enforce" them, such as the cause of action in 42 U.S.C. § 1983 or the criminal prohibition in 18 U.S.C. § 242—which the courts couldn't have made up on their own, despite the extraordinary chilling effects the freedmen faced…

I agree courts can't always effectively enforce every legal right. As Steve's examples show, they must often rely on the aid of other branches of government to enforce rights against private parties. But the main purpose of judicial review is to protect constitutional rights against the depredations of government. And, here, judicial review is an extremely effective tool, particularly in cases where effective enforcement simply requires striking down a law or regulation and barring state officials from enforcing those policies. In the case of SB 8, that means preventing state courts from hearing SB 8 cases that violate the Constitution and enforcing judgments that plaintiffs might win in such cases. States must not be allowed to forestall effective judicial review in such cases by exploiting loopholes in procedural doctrines. If the only way to prevent that is to close those loopholes by limiting the scope of some procedural precedents, then that is a small price to pay for vindicating much more important constitutional principles.

I close for now. But I expect we will return to these matters once the Supreme Court issues a decision in the SB 8 cases, which could be soon.

Show Comments (128)