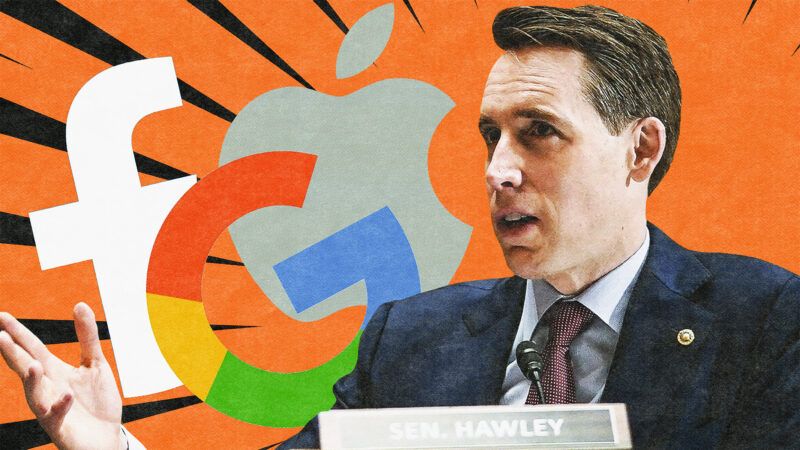

Josh Hawley's Dangerous 'Trust-Busting' Bill

Hawley’s legislation would give officials more room to unilaterally punish business behaviors they personally don’t like.

Sen. Josh Hawley's recently unveiled "Trust-Busting for the Twenty-First Century Act" would ban most mergers and acquisitions between companies worth over $100 billion, stop tech companies like Amazon and Google from promoting their own products, and subject vertical mergers to antitrust laws.

The Missouri Republican says these steps are necessary to counter the power of "woke mega-corporations," which he believes "control the products Americans can buy, the information Americans can receive, and the speech Americans can engage in." In Hawley's estimation, unregulated companies have "gobbled up our freedom and competition."

Hawley's comments aren't surprising. He has previously called for banning such social media features as infinite scroll and autoplay videos, declaring them "exploitative and addictive." He has also claimed that when Amazon uses third-party data to understand how better to market its own brands, it is violating antitrust law.

Hawley's new legislation takes aim at "dominant digital firms," defined as a website or service offered online with "dominant market power in any market related to that website or service." It views many actions taken by such companies as inherently "unfair and deceptive," and it would give the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission the power to regulate those behaviors.

For example, dominant digital firms would be banned from promoting their search results without informing consumers they were doing so, and mergers and acquisitions made by companies with a market cap over $100 billion would be prohibited.

But that's not Hawley's most radical proposition. His bill stipulates that "no acquisition shall be presumed not to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly only because the parties to the acquisition do not compete directly against one another at the time of the acquisition." This means vertical mergers (which occur between companies within the same supply chain that don't necessarily compete directly) would be subject to the same level of review as horizontal mergers (which occur between companies in direct competition).

The government currently views vertical mergers fairly positively and has not subjected them to antitrust scrutiny. Since they tend to reduce production costs and to pass savings along to consumers, they create an efficiency that benefits markets.

Hawley's bill would break with that tradition. This wouldn't just drastically increase the number of corporate actions the government will be able to review; it would increase the potential for this power to be abused by officials with political rather than legal complaints. Former President Donald Trump reportedly attempted to pressure the Department of Justice into banning a vertical merger between Time Warner and AT&T because of his personal dislike for the way CNN (owned by Time Warner) covered him.

By increasing the number of actions the government can review and stop, Hawley's bill not only increases the opportunities for future officials to derail perfectly harmless business activities; it runs the risk of bogging down commerce in regulatory processes. As the senator has noted, his bill would bar Amazon from adding new companies to its supply chain, a move that may hamper its ability to serve its consumers effectively.

Nor is this the only cause for concern. Hawley's bill would also reduce the burden of proof needed for corporate behavior to be deemed anticompetitive.

Current antitrust law does not view monopolies as inherently damaging to competition: Only when companies collude to exclude competitors, or when a single competitor tries to use force to achieve a monopoly, is there a problem. Hawley's bill would lower the burden of proof needed to prove a company is behaving unfairly. People alleging anti-competitive behavior would need only to show a preponderance of the evidence, and a plaintiff would not need to either "define the scope of a relevant market nor establish the share of such a market controlled by the defendant." Essentially, a person alleging monopolistic behavior wouldn't have to prove that a company actually had a dominant market share.

Further, it would not be up to an accuser to prove that a company's behavior damages competition. It would be up to the accused company to prove that its behavior doesn't damage competition. To beat an allegation, accused companies would have to show not only that their actions would increase competition but that they "could not obtain substantially similar procompetitive effects through commercially reasonable alternatives that would involve materially lower competitive risks."

Hawley's bill would also increase the cost of being found on the wrong side of the law: Companies found guilty of anti-competitive practices would forfeit all profits made from those actions.

The most troubling aspect of this legislation may be just how vague so much of it is. There is no real definition of what constitutes a "dominant" firm, even though businesses given this label are subject to scrutiny in many of their practices. This creates an opportunity for companies to abuse the Federal Trade Commission's enhanced investigatory powers to hamper their competitors. Worse yet, it creates the possibility that politicians will use their unilateral power to punish business behaviors they personally don't like.

Show Comments (76)