Everybody's Wrong About the Facebook/Murdoch Standoff in Australia

This tech/media fight down under is not about democracy or monopolies. It’s about ad revenue.

Once upon a time, not that long ago, your local newspapers were not just a community's major source for journalism. They were also one of the major ways that advertisers attempted to reach you with product deals, coupons, classified advertisements, real estate ads, and so on. Subscriptions never really covered the cost of publishing a newspaper. Ad revenue was largely responsible for a media outlet's profits.

Those days are dead, and they're never coming back.

The internet has become a much more effective and efficient way for consumers and advertisers to connect. Search engines (of all kinds), online sales, and targeted advertising have made the very prospect of poring through a newspaper's classifieds and retail ads comically obsolete. Media outlets have been struggling for about two decades to adapt to this tectonic shift and many have failed.

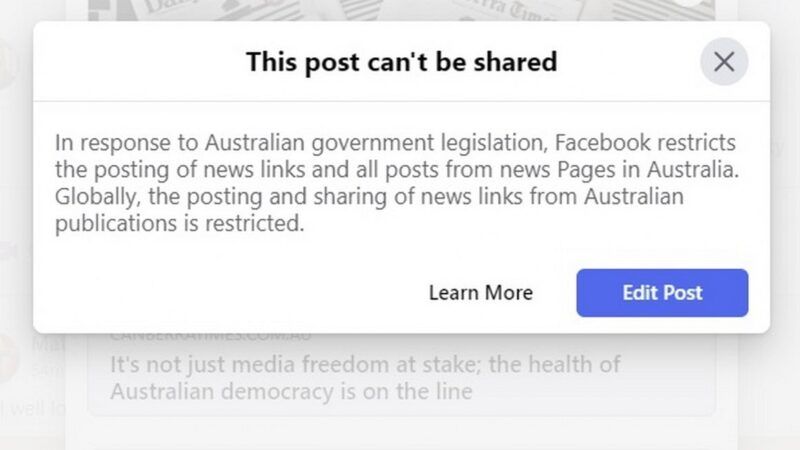

All of this is to say that the fight between Facebook and Australian media companies—which boiled over Wednesday with an announcement that Facebook would no longer allow users to share links to news stories from outlets based in Australia—is not about "democracy" or monopolies in any way, shape, or form. It's about advertising revenue, and who gets it.

In Australia, lawmakers are considering a bill that would require social media giants like Facebook and Google to pay what can bluntly be referred to as a "link tax." The government wants social media companies to pay media outlets for the "privilege" of users linking to news stories. The companies have been fighting back against these demands, arguing (accurately) that the media outlets are the ones that benefit from the links with page views that they probably wouldn't get otherwise. They've threatened to cut ties and stop linking to news content.

The Australian government didn't just decide out of the blue that tech companies need to subsidize media companies in order to preserve journalism for democratic purposes—the Australian government actually has a lengthy history of official secrecy and raids on media outlets and journalists who attempt to report on controversial stories. This proposed law is a result of lobbying by media companies and was pushed heavily by News Corp magnate Rupert Murdoch.

Facebook has decided they're not going to give in. William Easton, managing director of Facebook Australia and New Zealand, notes the very obvious reality that the company doesn't make money off of people sharing news links, and the media outlets benefit from the sharing more than Facebook does:

In fact, and as we have made clear to the Australian government for many months, the value exchange between Facebook and publishers runs in favor of the publishers — which is the reverse of what the legislation would require the arbitrator to assume. Last year Facebook generated approximately 5.1 billion free referrals to Australian publishers worth an estimated AU$407 million.

For Facebook, the business gain from news is minimal. News makes up less than 4% of the content people see in their News Feed. Journalism is important to a democratic society, which is why we build dedicated, free tools to support news organisations around the world in innovating their content for online audiences.

Some of the reactions have been as mind-numbingly dumb as one can imagine. Facebook has been accused of essentially censoring all news coverage in Australia, as though someone's only or primary mechanism for finding out about news is when his mother-in-law posts a link:

Whatever you think of Australia's news code, what Facebook's decision boils down to is that after all the commitments to quality news and free speech and so forth, when push comes to shove, the company is willing to block an entire country's access to news

— Mathew Ingram (@mathewi) February 18, 2021

"When push comes to shove" here means "When we're forced to pay media companies for a service that actually benefits media companies, not us." To wit:

If the US government passed a law requiring me to pay dinner guests I would have fewer dinner parties. I might just stop having dinner parties altogether. https://t.co/ykr2G6FwWV

— Matthew Feeney (@M_feeney) February 18, 2021

Here's the real deal. According to data from Australia collected over the past two decades, advertising revenue for newspapers has plunged 32 percent over that time, while circulation has remained largely the same. The overall advertising market has actually grown. Almost the entirety of the revenue loss for Australian newspapers has been the loss of classified advertising. It's been almost completely eliminated in the Australian print media because the technological efficiencies of internet searches make online classified systems much for useful for consumers. There's no reason for classified advertising in newspapers to exist any longer. Online is better. If you need proof, watch Saturday Night Live's recent parody advertisement about the nearly pornographic fascination some people have with searching for houses on Zillow.

This is all about the historically common disruption that new technologies cause in the marketplace. Newspapers are no longer the best at serving up advertising to consumers, so that market went elsewhere. After engines were invented, horses stopped being the most efficient way to travel. After electricity was invented, candles stopped being the most efficient artificial source of light.

Newspapers and media outlets have no moral right to claim this money for themselves. The advertising industry money should go to where it's most effective. But because media outlets have been unable to replace the lost advertising, they've resorted to lobbying the government with claims that preserving newspapers is pivotal to the survival of democracy, riding on the current populist criticism of the size of tech companies. And it's coming to America, if people like Rep. David Cicilline (D–R.I.) call the shots:

If it is not already clear, Facebook is not compatible with democracy.

Threatening to bring an entire country to its knees to agree to Facebook's terms is the ultimate admission of monopoly power. https://t.co/0JjTqtQhku

— David Cicilline (@davidcicilline) February 17, 2021

This absurd exaggeration of Facebook's power isn't just overheated rhetoric. Cicilline is the chairman of the House Judiciary's Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law. This is somebody who has a significant amount of influence on antitrust enforcement, and he's attempting to characterize Facebook's refusal to capitulate to demands to transfer money from one corporation to another as "threatening to bring an entire country to its knees."

Is siphoning money from one massive corporation to another "compatible with democracy"? Because that's where this is going. Google, it turns out, has buckled under the pressure in Australia and has compromised with an agreement to pay some money to develop a special platform for News Corp's properties in a special showcase. The New York Times notes that they're planning some deals with other media outlets soon.

Do you think Google will be making these deals with all news outlets, even the little ones? Of course not. This is a capitulation for which certain media companies that have lost ad revenue—but not political influence—will get financial subsidies from Google. Others will not. Google's compromise means that the most powerful media outlets will leave it alone, now that they've gotten their cut.

This has nothing to do with either democracy or antitrust issues. It's about one entrenched industry with political influence grabbing another industry by the ankles and shaking money out of it, with politicians serving as willing assistants, claiming that this is all for the public good (and filling their war chests with the political donations that will follow).

Show Comments (43)