Are Socialists More Like Libertarians Than We'd Prefer To Admit?

A libertarian goes to a conference on socialism and finds some surprising similarities.

"Are you interested in revolutionary politics?"

As I arrive at the location of the Socialism in Our Time Conference, a weekend-long summit organized by U.S. lefty mag Jacobin and the British Marxist journal Historical Materialism, a middle-aged woman approaches me to ask this question.

"I'm going in there," I say, gesturing toward the entrance, hoping this non-answer will suffice.

It does not.

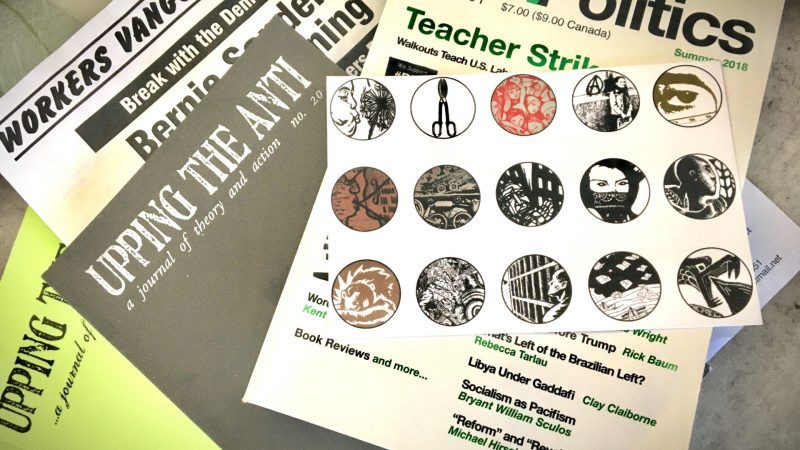

"In there," she says, I will not hear about the Russian revolution, or black liberation, or true workers' rights. Instead, I will hear about Bernie Sanders, who it is fair to say she does not support. She hands me a flyer from Workers Vanguard with the title "Bernie Sanders: Imperialist Running Dog."

Democrats are not the answer, she says. I can agree with that, I say. This turns out to be a mistake, for she proceeds to try to convince me to buy a subscription to a newspaper she and several other revolutionaries loitering outside the conference are representing. It's not the only sales pitch I'll encounter at the conference.

On the third floor, the registration area is flanked with tables peddling books, magazines, and political journals. One person is selling buttons and magnets made from old Archie comics, plus some artwork, including an eerie-yet-awesome image of Laura Palmer—the murder victim at the center of David Lynch's Twin Peaks—with eyes that follow me around the room. I have to resist the urge to buy it, settling for some magnets instead.

I stop at the table of a journal called New Politics, which the man behind the desk, Jason Schulman, says was known last century for pushing the "third way." Third way? Like the centrist Democrats? Bill Clinton? Ah, no. "Neither Washington nor Moscow," Shulman explains.

At a table for another political journal, Upping the Anti, from Canada, I pick up issues promising articles on safe-injection sites, the drug war in Canada, and state surveillance. There's also a piece on "liberatory midwifery practice" from a registered midwife who pushed for "the right to access state-funded midwifery" only to reckon with "the trade-offs that state-sanctioned and funded midwifery would bring." The burdens of state licensing of midwives are categorized not as a problem of government overreach, but of "class and white privilege" and being "petty bourgeois in orientation."

Some of the books on display would be right at home on libertarian or anarchist bookshelves, but there are also plenty of covers featuring famous communists and hammers and sickles. Others seem almost like bizarro-world versions of the sorts of articles that might appear in this magazine: Marx at the Arcade. Union Power. Occult Features of Anarchism. Climate Leviathan.

It wasn't the only time I was struck by the quasi-overlap—a kind of uncanny valley similarity—with the ideological movement politics I regularly encounter in libertarian circles. As a libertarian at a socialist conference, I found plenty to object to and, on occasion, snicker at. But I also couldn't stop seeing ways we're all more alike than we'd like to admit, and wondering if that's what really matters.

The two-day conference is set up as a series of hour-and-a-half-long panels, with about a dozen options per time slot. The panels all fall into one of 13 categories, including "Colonialism and Anti-Imperialism," "Historical Interrogations," "Left Strategy," "Labor," "Queer Theory," and "State Theory." They bear little resemblance to the kind of leftist topics and slogans that dominate online and in popular politics.

I start with a panel called "Perspectives on Socialist Strategy in the Democratic Socialists of America" (DSA), which seems likely to offer the most tangible and timely information. Speakers come from different caucuses of the DSA, including a libertarian socialist faction represented today by John Michael Colón. He says libertarian socialist caucus-members are "not strictly anarchist" but are "united by a generally anarchistic conception of socialism," where democratically run "counter-institutions to the state" provide many services in conjunction with a more minimalist democratically-run government.

One thing that quickly becomes clear is that DSA socialists are a factional bunch, and new splinter movements are perpetually rising up to challenge the old guard. Several of the caucuses represented on the panel had just been formed in the past year or two. And while the libertarian-socialist group is the oldest continually-running DSA caucuses, it, unfortunately, seems out of step with the others, all of which seem to envision a dramatically larger role for the state and less room for private enterprise.

The Bread & Roses Caucus, for example, aims to fuse "a reborn and mighty workers' movement" with the smaller Socialist Movement and advocate for things like Bernie 2020, Medicare for All, and the Green New Deal, according to a panelist named Neil. He says the '90s and 2000s "will hopefully be the nadir of the socialist movement."

The Socialist Majority Caucus, meanwhile, wants to "directly confront capitalist economic and political power," says panelist Renée Paradis. It's hoping to move beyond the inter-DSA struggles that have consumed a lot of the party's time in the past few years—a result of the group effectively going "from a series of book clubs to a mass organization overnight" in 2016, she says—and help usher in a permanent socialist majority in the U.S. electorate.

The North Star Caucus, perhaps the most conventional of the bunch, is concerned with countering Trump and "the far right" first and foremost, according to audience member Ethan, who happens to be a North Star member. He said their "view reflects the more Michael Harrington vision" of the party. Harrington was a 20th century author and labor organizer who, in the 1960s, debated free market advocates like Milton Friedman and William F. Buckley Jr. and also objected to more radical contingents of the young left. He went on to help form and then chair the DSA, believing that socialists must work within the Democratic Party. The divide between work-from-within partisan politics on the one hand and radical activism on the other is one that will be familiar to many libertarians.

Ethan volunteers this information from the audience because the North Star panelist, Miriam Bensman, is running late.

When Bensman arrives, she apologizes to everyone in the room for "overestimating the [Metropolitan Transit Authority's] capacity," and folks snicker. I hate when people ask libertarians about using public roads, so I promise myself not to use her comment to set up some snark about government-run transit. I slip out to catch a different panel, where another speaker is also late. As I enter, she apologizes, then blames the unreliability of the New York City subway. I amend my position. I will not snark, but I will…mention this.

There is no free lunch at the socialist conference, so we all break. Outside, the anti-Sanders crowd is now arguing with several police officers, who are telling them they must move and can't hand out flyers right in front of a school. The group is trying to make the cops see how important it is that they counter the message of those inside. The cops look bored.

While watching, I strike up a conversation with Paradis, the panelist from earlier. I tell her I enjoyed hearing about DSA infighting because it makes me feel better about faction-splitting within libertarian circles. She says electoral politics are her main concern, but she came to the DSA from more standard liberal circles after looking at more progressive political issues and solutions through a more systematic and class-conscious lens. She appreciates the DSA for elevating concerns often ignored by mainstream politics.

I tell her, more or less, same, but for libertarianism. So many of the people I know in libertarian politics are working on the same issues that keep coming up at the conference—criminal justice reform, immigration reform, barriers to health care and employment among the working classes, crony capitalism and the unfair advantages it creates. All the ways an overreaching government hits more marginalized people and communities harder.

"Not just lowering taxes and gun rights," I say. She nods, then gives me a look that seems skeptical, though I may be projecting. I am dead serious, of course, but this is not a place where I expect to be believed. Then Paradis says, "I'm really hung over."

Of course. Never reach for elaborate ideological explanations when the mundane and human will suffice.

I look over to check in on the Workers Vanguard and the cops. They have agreed to move about 30 feet down the sidewalk. The woman I talked to earlier is walking by now and stops to look at me talking to Paradis. I suddenly feel ashamed. This is not the revolutionary vanguard, it's the accommodation faction! For a brief moment, I want to tell the older woman, don't worry, I am not on this one's side! But I'm not on the Russian Revolution Redux side, either. What is happening to me? Am I worried about being first up against the wall?

I'm going to go get lunch, I tell Paradis. She is going home to take a nap. Au revoir, comrade.

After lunch, I hit up the "Law and Social Movements" panel, which, based on the name, could be about almost anything. It turns out to be a robust discussion of totally disparate topics from organizers in the reproductive rights, immigration reform, and LGBTQ spheres.

As so often happens with socialists, I found myself nodding along for much of it while periodically recoiling in horror. One panelist, Lea Ramirez, speaks out against immigration quotas that favor only highly-skilled workers from particular countries (yes!), but locates the source of historic and current immigration restrictions at large not with nativism, populism, and state control, but with "the capitalist class" and its pursuit of "a highly exploitable" workforce. Somehow, by keeping immigrants out and driving up the price of native-born U.S. labor, those wily capitalists are pursuing their bottom line.

Talking about recent abortion battles in New York State, Megan Dey Lessard expresses disappointment with how little that mainstream Democratic politicians and women's rights groups seemed willing to settle for. They were content to allow regulators to control women's bodies so long as it was through "public health code" rather than criminal laws, she complains. And after pushing through a largely symbolic bill, expressed a wish to move on to sex education advocacy.

Perhaps more so than with either mainstream "liberals" or "conservatives" these days, the far left tends to sound oddly similar to libertarians in a lot of ways—though neither group is keen to admit it. Democratic socialists are often willing to reject the endless litany of empty slogans, Culture War, and partisan kitsch of Republicans and Democrats. They are willing to speak up for civil liberties, and the dignity of the imprisoned, no matter who is in the White House, and they maintain a level-headed skepticism about the convenient political narratives, mostly centered on presidential personalities, that tend to dominate cable news.

That's why the end-game solutions proposed by hardcore leftists always boggle my mind. How does anyone look at these systems and incentives, accurately see so many of their flaws—and then suggest that we can win by giving government thugs more control?

Granted, Medicare bureaucrats are not exactly Border Patrol agents. But give them enough power and remove private alternatives, and the distinction becomes almost irrelevant. With a monopoly and moral certitude and a multi-billion-dollar budget, any arm of the state will eventually start operating in unintended, power-hoarding, and corrupt ways that hurt society's most marginalized. At the very least, they will consistently fail to perform adequately for large numbers of the people they are supposed to serve.

Lessard alluded to this, recalling Carmen Rodriguez, a Puerto Rican woman who died during an abortion at a New York City hospital in 1970, not long after the state made it legal to terminate pregnancies with a doctor's permission. The city's municipal hospitals "were in shambles," with one Bronx hospital "able to perform three abortions per day" with waiting lists of hundreds of women "and people just lining up at the door," Lessard said. Rodriguez's death from heart complications after the procedure served as a "flashpoint" for rallying around the need to "reclaim medical spaces" and expand "access to medical spaces in general."

"Yes, abortion had become legalized," but there was still "a gap between legalization and access," Lessard said.

This is where capitalism comes in. Socialists often want to treat it as pure evil, a haven for corruption and amoral behavior. But capitalism is just an economic system where the provision of goods, services, and labor is determined by individuals negotiating with each other, rather than by a centralized state authority. Capitalism makes possible what government, paternalism, or altruism alone cannot.

In a market-oriented system, private clinics—be they worker-run cooperatives, privately-funded philanthropic endeavors, or your traditional for-profit physician's office—can step in and fill the void. And in the decades since the '70s, many have. It wasn't capitalism that kept 20th century women from having abortions, but the state. And it's not capitalism that's now leading to clinic shutdowns, but politically motivated "public health" laws and other government policies.

Even more than most health care, reproductive health services are saddled with high levels of regulation that strictly limit where, when, and how they can operate. These regulations go far beyond basic safety standards, and they represent a significant barrier to the provision of reproductive health services.

What New York City women need, and have always needed, are freer, less regulated markets for contraception, abortion, and all-around reproductive health care, not more government-managed services.

In substance and style, there are plenty of differences between a socialist conference and its libertarian equivalents. The historic school setting may have leant itself to an old book-swap vibe last weekend, but it also allowed for a level of radical chic no Marriott conference center can. Beyond the aesthetic realm, the gap grows even wider.

It's hard to pinpoint any particularly dominant political platform from the motley group of academics, organizers, journalists, DSA members, authors, and others (including a good number of folks from the U.K. and Canada) who were gathered at the Socialism In Our Time conference. Yes, many called for expansion of government's role in health care, environmental regulation, and numerous other matters, but others questioned various facets of state authority, regulation, and power. There's no getting around the fact that their ready explanation for pretty much all of society's ills—capitalism—is what libertarians offer as a solution to an equally large variety of issues. Our core beliefs are fundamentally at odds.

Still, I got a kick out of the similarities. The lopsidedly male crowd. The mix of media types and the professionally political, earnest kids, disheveled academics, and dour lifetimers. The feuding factions and squabbling cliques. The hangovers. (Oh god, the hangovers.) The obsession with dead economists. The bitter—yet hopeful—relationship to mainstream politics. The endless tiffs over immigration. The emphasis on the concrete over the symbolic on the one hand, and the stubborn attraction to a few passionate slogans on the other. In so many ways, libertarian and socialist gatherings feel like strange mirror images of each other.

For both libertarians and socialists, most of society's problems can be traced back to a single root cause. For socialists, it's capitalism. For libertarians, the state. But unless you're a hardcore anarchist or the most ardent communist, there's a place for both. And the most insidious problems often flow out of intimate, ugly, accountability-free alliances between the two.

I know we can't kumbaya our way out of this. Many of the major policy divides between libertarians and socialists are real and powerful. They can't all be resolved by turning our collective sights on the worst and agreed-upon abuses. But there are still so very many of those abuses to conquer. It seems like maybe that's what we should try to do.

So to answer the question of the woman I met outside the conference: Yes, I really am interested in revolutionary politics. That's why I'm a libertarian. Radical respect for empowering individuals over the state is where my revolutionary sympathies lie.

And I know that however absurd or impossible it sounds, there are a lot of libertarians, leftists, Democratic Socialists, Libertarian Party members, independents, anarchists, conservatives, liberals, and Americans of all or no political affiliations who agree—or, at the very least, think and talk about politics and society in surprisingly similar ways. It can't hurt for us revolutionaries, whichever side we're on, to occasionally remember that.

Show Comments (266)