Global Gene-Edited Baby Ban Urged

Why should an international panel of experts get to decide if you will be allowed to gene-edit your kids?

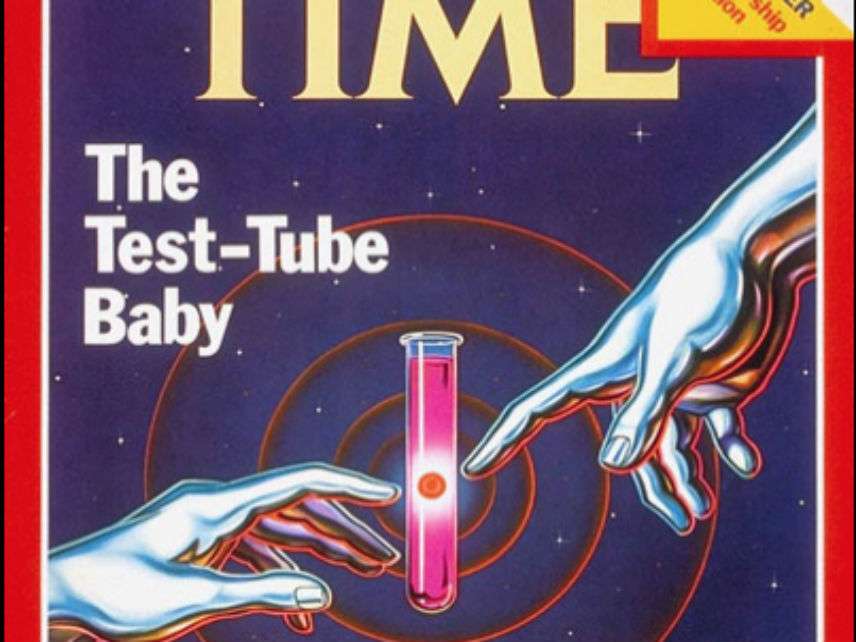

The American Medical Association called for a moratorium on experiments that would seek to implant a "test tube baby" into a woman in an editorial in the May 1, 1972, issue of its journal. The association asserted that the ethical implications of this and other experiments in "genetic engineering" should be thoroughly explored before the work is applied to human beings. Ethically speaking, a Harris poll just two years earlier reported that a majority of Americans believed that producing test-tube babies was "against God's will."

Subsequent to the AMA's statement, research on in vitro fertilization (IVF) essentially halted in the United States until British researchers announced the imminent birth of just such a test tube baby—Louise Joy Brown—in July, 1978. The consensus about the morality of IVF then flipped and the Gallup poll a month later reported that 60 percent of Americans approved of IVF and more than half would consider using it if they were infertile.

The first IVF baby born in the United States was Elizabeth Carr in 1981. Since then, more than 8 million babies have been born as a result of IVF and other advanced fertility treatments.

In Nature, a group of eminent researchers are now advocating a moratorium on heritable human genome editing. "We call for a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing—that is, changing heritable DNA (in sperm, eggs or embryos) to make genetically modified children," they write. "By 'global moratorium,'" they hasten to add, "we do not mean a permanent ban."

The proposed moratorium is in response to the widely condemned announcement in November by Chinese biophysicist Jiankui He of the birth of two baby girls upon whom he had applied CRISPR gene-editing when they were embryos to silence a specific gene related to HIV-infection resistance. Interestingly, other research suggests that silencing that gene would likely enhance the girls' intelligence. While the Chinese government hurried to condemn He's gene-editing, more recent reporting suggests that the government may well have known and approved of what He was up to. Since it looks like He failed to adequately inform his patients with regard to how technically premature his version of gene-editing was, and what he was hoping to achieve by using it, he should be sanctioned by the relevant authorities.

In their Nature article, the researchers suggest that a global moratorium be adopted for five years during which time an international framework be set up for considering the safety and ethical aspects of inheritable gene-editing of human embryos. Under the proposed framework, an international coordinating body would be established, the goal of which would be to foster a "broad societal consensus" on "whether to proceed with human germline editing at all, and on the appropriateness of the proposed application[s]." By broad societal consensus, the researchers do not mean unanimity or simple majority. "Societal consensus on germline editing is something that must be judged by national authorities, just as governments make political judgements about their citizens' views on other complex social issues," they write.

This call for setting up an international framework is a bit behind the times. The World Health Organization already announced a month ago the creation of a 18-member Expert Advisory Committee on Developing Global Standards for Governance and Oversight of Human Genome Editing.

But why does there need to be a "broad societal consensus" before would-be parents are allowed to access the benefits of gene-editing for their prospective children? There was certainly no such broad consensus before Lesley and Peter Brown decided to risk then-novel IVF treatments in order to bear their daughters Louise and Natalie.

Let's consider the concerns that the researchers suggest merit the effort of achieving a broad societal consensus. They warn:

The societal impacts of clinical germline editing could be considerable. Individuals with genetic differences or disabilities can experience stigmatization and discrimination. Parents could be put under powerful peer and marketing pressure to enhance their children. Children with edited DNA could be affected psychologically in detrimental ways. Many religious groups and others are likely to find the idea of redesigning the fundamental biology of humans morally troubling. Unequal access to the technology could increase inequality. Genetic enhancement could even divide humans into subspecies.

Moreover, the introduction of genetic modifications into future generations could have permanent and possibly harmful effects on the species. These mutations cannot be removed from the gene pool unless all carriers agree to forgo having children, or to use genetic procedures to ensure that they do not transmit the mutation to their children.

These are strawmen, but let's knock them down anyway.

Forbidding parents from taking advantage of gene-editing, thereby mandating that their children run the risks of being born disabled, is immoral.

Outlawing gene-editing will not eliminate peer pressure on parents to provide advantages to their children.

The fact that children born via IVF are psychologically and cognitively normal suggests that gene-edited ones would be, too.

Religious groups that oppose gene-editing don't have to use it to reproduce, and they should not be allowed to impose their beliefs on reproductive "sinners."

All new beneficial technologies are initially accessed unequally, but eventually become more widely available.

If two people belonging to different human subspecies fall in love, they can overcome barriers to fertility by resorting to improved assisted reproduction to bear children.

If a genetic modification proves harmful to an individual, he or she can use improved assisted reproduction to make sure that his or her progeny are free of the deleterious mutation.

Rather than resorting to international commissions to devise regulations, the United States offers a successful hands-off model for how assisted reproduction—including gene-editing of embryos—should be governed. The federal government requires laboratories engaged in assisted reproduction to be certified by organizations such as the American College of Pathologists and to report certain data to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Otherwise, guidelines issued by private professional organizations, such as the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), account for most governance of assisted reproduction. Regarding germline gene-editing, the ASRM has endorsed the American Society of Human Genetics statement that declares, "At this time, given the nature and number of unanswered scientific, ethical, and policy questions, it is inappropriate to perform germline gene editing that culminates in human pregnancy."

A 2018 Pew poll provides some indication of a broad societal consensus among Americans with respect to gene-editing prospective children. In that poll, 72 percent of Americans approved of gene-editing an unborn baby to treat a serious congenital disease or condition, and 60 percent approved of gene-editing to reduce a baby's risk of developing a serious disease or condition over their lifetimes. As of now, only 19 percent think gene-editing to an enhance a baby's mental or physical characteristics is appropriate. Once germline gene-editing achieves a high degree of safety and accuracy, most people will find it ethically unproblematic, just as folks did in the case of IVF 40 years ago.

Ultimately, it should be no else's concern—even the concern of an august panel of international experts—if adequately informed parents choose in the future to use safe gene-editing with goal of benefiting their prospective children.

Show Comments (55)