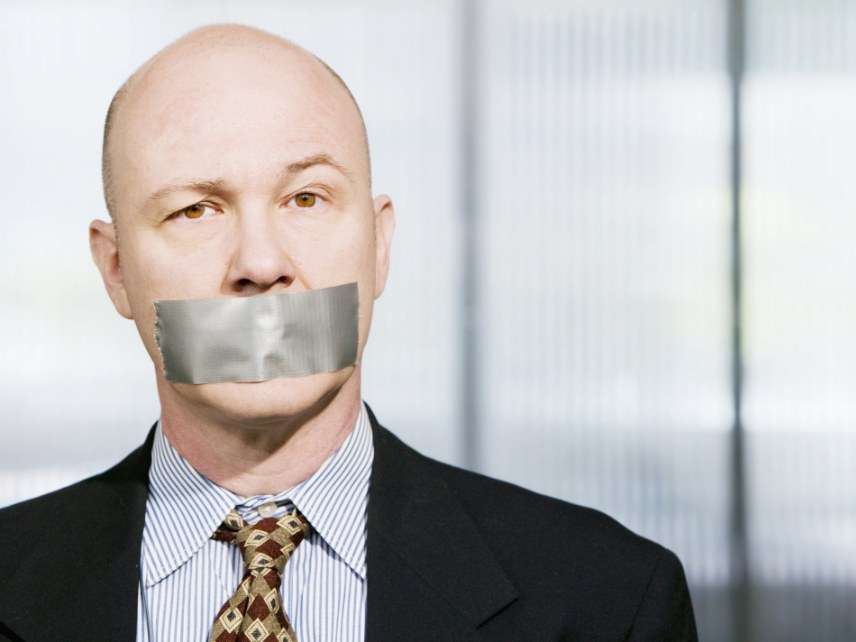

The Feds Are Using a Gag Order To Censor a Critique of Its Prosecutions. Bring on the Lawsuits.

The Cato Institute and Institute for Justice team up to fight for the right to publish a book attacking behavior by the SEC.

The liberty-loving attorneys of the Institute for Justice are teaming up with the Cato Institute to fight a federal policy that forbids defendants from discussing the terms of civil settlements they enter into with the federal government. If they don't keep their mouths shut, these defendants are threatened with harsher punishments.

The offending agency targeted in a federal lawsuit filed today is the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The Cato Institute wants to publish a book by an entrepreneur who believes he's the victim of prosecutorial overreach by the SEC. But he can't tell his story for fear of further prosecution.

Normally this is the point where we'd tell you who this person is and why the SEC went after him. But we cannot. As part of the agreement he reached to settle the matter, the plaintiff in the Cato suit had to accept a gag order that prevents him from discussing or criticizing the case. Even though the settlement does not require him to admit guilt, he is nevertheless forbidden from saying anything that would indicate that he thinks the "complaint is without factual basis."

Because this gag order prevents him from talking about the case, it also prevents the Cato Institute from publishing his book. Cato and the Institute for Justice are thus not revealing the man's identity because doing so would also reveal that he disagrees with, and is critical of, his settlement with the SEC. If he violates the gag order, SEC prosecutors could try to vacate the settlement and punish him more harshly.

Over at the Cato Institute, Clark Neily, vice president for criminal justice, explains about as much as he can without revealing the specific case:

The case began when a well-known law professor introduced us to a former businessman who wanted to publish a memoir he had written about his experience being sued by the SEC and prosecuted by DOJ in connection with a business he created and ran for several years before the 2008 financial crisis. The memoir explains in compelling detail how both agencies fundamentally misconceived the author's business model—absurdly accusing him of operating a Ponzi scheme and sticking with that theory even after it fell to pieces as the investigation unfolded—and ultimately coerced him into settling the SEC's meritless civil suit and pleading guilty in DOJ's baseless criminal prosecution after being threatened with life in prison if he refused.

Most SEC cases—98 percent of them, according to the Institute for Justice—end in settlements. If each of these settlements includes a similar gag order, that means almost no one targeted by the SEC can publicly discuss or evaluate the merits of the case against them. We do not have the ability to consider whether citizens are coerced into accepting these deals because they cannot afford to fight back, not unlike what we see in many criminal court cases.

These agreements only bind in one direction. Here's a recent press release from the SEC that details the settlement with a securities firm executive, emphasizing the accusations of fraud against him but noting that he neither admitted nor denied guilt when accepting the judgment. They get to describe these cases how they choose; defendants have to remain silent out of fear. Here's a whole page of links to these press releases.

Jaimie Cavanaugh, an Institute for Justice attorney working on the case, tells Reason that these SEC actions start with the agency threatening their targets with massive prosecutions and then settling for fines and allowing the person to forego an admission of wrongdoing. Those fines seem to correspond with the amount of money that person or company's insurance will cover, Cavanaugh says. That should raise concerns over whether these enforcement mechanisms are being used for revenue generation—a white-collar version of asset forfeiture, if you will. The censorship keeps the public from evaluating the extent that this might be happening.

"We think the book would tell the story of what's happening to lots of people," Cavanaugh says. And it's not just the SEC. Other agencies like the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Commodity Futures Trading Commission write similar gag policies into their settlements.

The lawsuit from the Institute for Justice, filed in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, seeks to have this gag order declared an unconstitutional violation of the Cato Institute's First Amendment right to publish this man's book. They're asking for an injunction to stop the SEC from enforcing these gag orders.

Read the complaint here. A spokesperson from the SEC declined to comment in respone to the filing.

Show Comments (27)