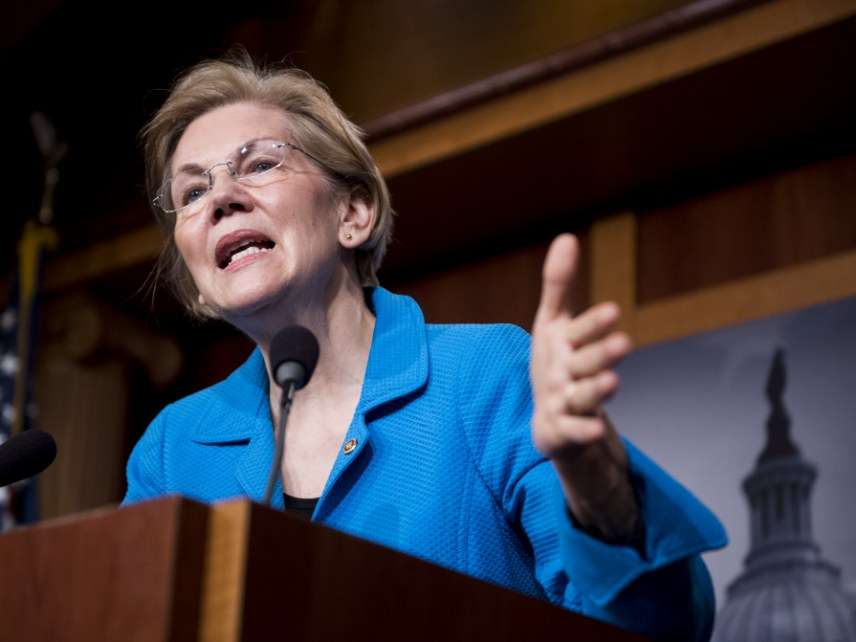

Under Trump, Elizabeth Warren Suddenly Discovers the Downside of Unaccountable Federal Agencies

Maybe don't give the other side the rope to hang you with.

If Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren had taken a page out of Virginia Delegate Nick Freitas' book, she might not be in the pickle she is today.

Warren is spitting mad at Mick Mulvaney, the Office of Management and Budget director who does double duty heading up an agency whose creation Warren championed: the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The CFPB's previous director was an ideological ally of Warren. Since Mulvaney took over, Warren has ripped the agency's decisions. Warren said Mulvaney is giving "the middle finger" to consumers, and she railed at Mulvaney's indifferent response to the 10 (!) letters she has sent him demanding answers to more than 100 questions.

The other day she tweeted that she is giving Mulvaney "one last chance." Yet as The Wall Street Journal points out, she has only herself to blame for her apparent impotence.

Time and again during debate over the CFPB, conservatives and libertarians warned that its powers were too great and that its accountability to the other branches of government was too limited. But that was just the way Warren and other supporters wanted things. Neither Congress nor other political forces could influence an unaccountable regulatory agency. Now Warren finds herself thwarted by the very lack of oversight she championed.

Be careful what you wish for.

Freitas, who is running for the Republican nomination for Senate in Virginia, made this very point on Saturday in his debate against Corey Stewart, the bombastic chairman of the Prince William Board of Supervisors.

Asked whether the federal government should punish local officials who defy federal immigration laws, Stewart said yes: "Prosecute any local or state official who declares themselves [sic] a sanctuary city," he said.

Freitas took a different view: "If we ever, God forbid, had a Hillary Clinton presidency, and they passed federal gun bans, when a sheriff … refuses to enforce it the federal government is going to go in and put that person in jail."

Freitas draws out an important point: When you think about what you want government to do, put specifics aside and focus on the more general principle.

Philosopher John Rawls famously invented a mechanism for doing just that: the "veil of ignorance": If you are designing the rules for a society, you should assume that you know nothing about your place in that society. If your race, age, physical abilities, mental prowess, and so forth are all a complete mystery, then you are likely to design a political-economic system that is fair to all. Just in case you wind up at the bottom of the social pile.

Having a president who makes policy through signing statements, his "pen and phone," and other forms of executive action, for example, seems brilliant when the opposing party controls Congress. It seems less so when the opposing party controls the White House.

Should intelligence agencies keep tabs on Islamists who might pose a threat of domestic terrorism? Then don't be surprised if a different administration turns the focus to right-wing militias.

California lawmakers have passed sanctuary legislation protecting illegal immigrants from deportation. Stewart—who, in an ironic twist, spent much of last year cheerleading for neo-Confederate causes—thinks they should be arrested for it. But as Freitas points out, that could set a precedent Stewart might one day regret.

Speaking of California: The Supreme Court will soon decide a case about that state's abortion-notice law. The law requires anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers to post notices that the state offers contraception and abortion at little or no charge. Abortion-rights activists say this is necessary for consumer protection.

But while giving the government the power to compel speech might sound good to abortion supporters in liberal California, they might not like to see that power exercised elsewhere. Imagine Mississippi forcing clinics to post signs bearing the anti-abortion slogan "Abortion stops a beating heart" and advising women where they can find adoption services.

Circuit courts already have split on another form of compelled speech: Forcing doctors who perform abortions to conduct an ultrasound, display the results to the patient, and offer to let her hear the fetal heartbeat. Conservatives who don't like the California law tend to favor this sort of compelled speech—and liberals who find compelling speech by a doctor offensive are much less troubled at the thought of compelling bakers to make wedding cakes for gay couples.

It is not enough simply to think you might not always hold the reins of power. It's also prudent to wonder what your enemies would get up to if they held them—because someday, they will.

Show Comments (165)