Judge Tells Trump to Pretend to Listen to Twitter Haters

A lawsuit leads to a suggestion that the president engage in a kinder, gentler ignoring.

In order to resolve an unusual First Amendment lawsuit over whether President Donald Trump can block people on Twitter, a federal judge has a suggestion: What if he just pretended to listen to them?

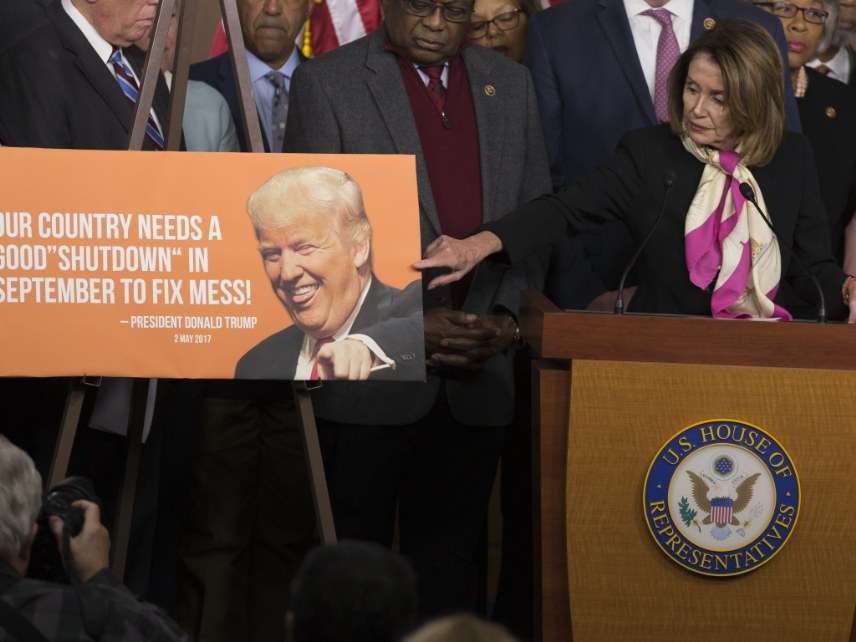

The Knight First Amendment Institute and seven individuals are suing the Trump administration because of Trump's tendency to block people from following his "official" Twitter account if they tweet mean things at him.

A lawsuit sounds absurd, but there are some interesting First Amendment implications surrounding it. Trump and his administration are using a private social media account on a private platform to communicate public messages about important policy decisions. People who are blocked from following the president cannot see these messages. It's not just about sending sarcastic comments to the president. Blocking also makes it difficult to see what the president of the United States is saying.

U.S. District Court Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald in Manhattan seems to be trying to navigate this complicated problem without setting some sort of precedent over censorship, speech, free association, and private social media platforms. She pitched a suggestion to both sides in the lawsuit yesterday: What if Trump merely "muted" these people instead of blocking them?

To explain to those of you who have managed to avoid getting sucked into Twitter's vicious gravity: Muting a person on Twitter is essentially a secret block. If President Trump were to mute you, you'd still be able to follow him and see his tweets. But he would never see any tweets or messages you directed his way. In old-fashioned postal delivery terms: Blocking is when the post office returns a letter with a "delivery refused" notice; muting is when they just quietly toss it in the trash without saying a word to you.

So if the president were to merely pretend that he was listening even though he wasn't, this could potentially satisfy both sides. Notes The New York Times:

Katie Fallow, a lawyer for the Knight Institute, said that she was receptive to the possible compromise. She noted that muting would be "much less restrictive" of her clients' rights.

Nicholas Pappas, a comedy writer and one of the seven plaintiffs, told a gathering of reporters after the hearing that it would be "a great solution," if he were muted, rather than blocked, by the @realDonaldTrump account. (Mr. Pappas was blocked by that account after tweeting in June: "Trump is right. The government should protect the people. That's why the courts are protecting us from him.")

There's something so very telling about the relationship between citizens and government authority that's implied in this proposed compromise. These people can be satisfied as long as they can send their messages to Trump, even though he'll never see them or read them or even remotely care about them. (OK, so they also want to be able to see and quote the president's tweets, which in theory they can't do if they're blocked, though there are well-known workarounds. And practically every tweet from the president gets media coverage these days.)

No doubt many folks who have attempted to give feedback to government can relate. President Barack Obama's administration made a big deal about its "We the People" petition site, where citizens could attempt to get responses from the White House over their pet issues. But as the site grew popular, the White House increased the signature threshold to even get a response to try to hold back the trolls. As I noted back in 2013, it appeared that all the administration used the petition site for was to provide "a justification for what the administration is doing, wants to do, or has already done rather than an indication of the administration actually changing a position based on public dissatisfaction."

In the end, all the judge is suggesting here is that the Trump administration do a better job of pretending to care about what members of the public have to say. That people know it's just a pretense but will be happy anyway probably says more about the frustrated state of our communications with those who control the government than it does about the First Amendment.

Show Comments (141)