The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

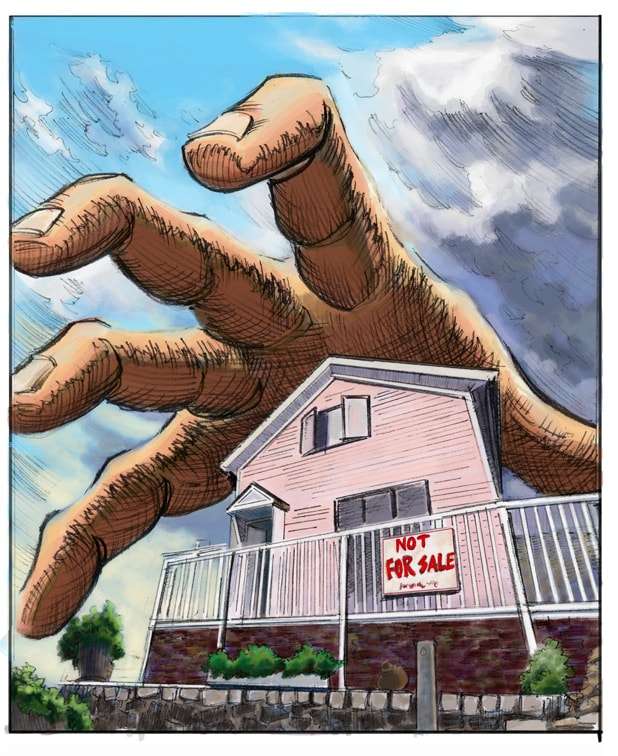

Potential pitfalls of building Trump's Great Wall of eminent domain

In order to build his much-ballyhooed wall across the Mexican border, Donald Trump is likely to have use eminent domain to seize large amounts of private property. But as legal scholar Gerald Dickinson explains in a recent Washington Post article, that may not be easy:

In trying to take land for the wall, the federal government would be held to time-consuming procedures that include consultation and negotiation with the affected parties - including private landowners, tribes, and state and local governments - before taking any action. Federal law requires the government to consult with "property owners … to minimize the impact on the environment, culture, commerce, and quality of life for the communities and residents located near the sites at which such fencing is to be constructed." Then the government would need to declare a taking and undergo condemnation proceedings….

The takings clause [of the Fifth Amendment] also protects private landowners from uncompensated seizures. Owners who are subject to eminent domain to build the wall would have to receive compensation for its physical presence on their property. Successfully measuring the value of the land and settling on prices for hundreds of owners with unique property interests, however, would be the "deal" of the century. Determining just compensation is not easy in contested cases in which the land and property at stake are infrequently exchanged on the market. There are few other properties in the United States situated along an international boundary, some of which is already fenced, which makes fair value hard to establish….

[T[hat's a lot of ammunition for hundreds of landowners. If the rollout of Trump's hastily drafted travel ban is any indicator, we should expect sloppy execution of statutory requirements and takings procedures if the administration attempts to condemn border land.

As Dickinson points out, contested takings sometimes take years to resolve, and this use of eminent domain is likely to be larger and more complex than almost any other in recent years. It could take years of legal battles and negotiation and billions of dollars in litigation costs and compensation payments before the federal government can secure all the necessary land.

Dickinson adds that some of the property in question is owned by Native American tribes, which raises additional difficult legal and political issues that might also take a long time to resolve. Battles over tribal sovereignty and property rights often raise unusually complex questions.

The Fifth Amendment also requires that eminent domain only be used for a "public use." In the notorious case of Kelo v. City of New London, the Supreme Court ruled that almost any potential public benefit qualifies, including even transferring the condemned property to a new private owner who might provide "economic development" for the community. It did not even matter that the plan in question was extremely dubious and eventually left the community with a deserted wasteland used mainly by feral cats. Trump has a long history of eminent domain abuse of his own, and is a big fan of the Kelo decision. He likely knows that the decision would justify taking property for his wall, regardless of whether it produces any genuine public benefit or not.

In fairness, taking property for a government-owned wall is likely to satisfy even the much narrower original meaning of public use, which restricts takings to government-owned projects and private owners who have a legal duty to serve the entire public (such as public utilities). The border wall falls in the former category.

But even if the use of eminent domain to build the wall doesn't violate the Public Use Clause, it will not be easy for the federal government to deal with the relevant procedural issues and come up with adequate compensation. Trump will at least need Congress to allocate substantial funds for the latter purpose.

Both Dickinson and political scientist Logan Strother argue that the use of eminent domain to build the wall is likely to attract strong public opposition. The Kelo decision generated widespread outrage across the political spectrum, as both right and left found reason to oppose the seizure of homes for transfer to private business interests. Trump was one of the very defenders of the decision, probably because it facilitated the seizure of land for transfer to politically influential developers like himself. Dickinson suggests that the wall takings might generate comparable opposition:

The Great Wall of Trump could leave hundreds of Cokings and Kelos at risk of losing their property. Pressure for Trump to back down will mount; these types of land grabs spark public outrage. After Kelo, there was a state-led backlash: Within several years of the decision, most states had enacted legislation giving owners additional property protections.

Americans do not take kindly to threats to fundamental principles of property ownership, even if some of them (though not most, polling shows) like the concept of the wall and the immigration policy Trump wants to pursue. It is not inconceivable to think we are heading for another Kelo saga. The wall could lead to the backlash of the century: a resistance movement laced with political, cultural, social and economic consequences.

I am skeptical that wall takings would generate as widespread a backlash as the Kelo case did. The latter was overwhelmingly opposed by both Democrats and Republicans. The wall, by contrast, enjoys strong support from Republican partisans. Many of them are likely to hold firm even if it means forcibly displacing large numbers of property owners. Still, a significant negative reaction could easily arise. The wall proposal is already unpopular. A recent Quinnipiac poll finds that 60 percent of Americans oppose it, with opposition rising to 65 percent if the US has to pay for it. The latter scenario, of course, is by far the more likely one, despite Trump's ridiculous campaign promise that Mexico will somehow put up the money.

Other recent polls reach similar results, such as a Pew Research survey that found 62 percent in opposition to the wall. When and if the takings begin on a large scale and media attention focuses on victims with sympathetic stories like those of the property owners in the Kelo case, opposition might rise still further.

At the very least, the use of eminent domain to build Trump's Great Wall might remind Americans that immigrants are not likely to be the only victims of Trump's hyper-restrictionist immigration agenda. It also threatens the liberty and property rights of native-born citizens.

Show Comments (0)