Democrats' Latest Plan to Save Net Neutrality Is All Bark, No Bite

There is roughly a zero percent chance Democrats will succeed in blocking net neutrality repeal through the Congressional Review Act.

Senate Democrats think they've found a way to preserve Barack Obama's net neutrality rules. Like their plans to reimpose the rules at the state level, the new gambit has a roughly zero percent chance of succeeding.

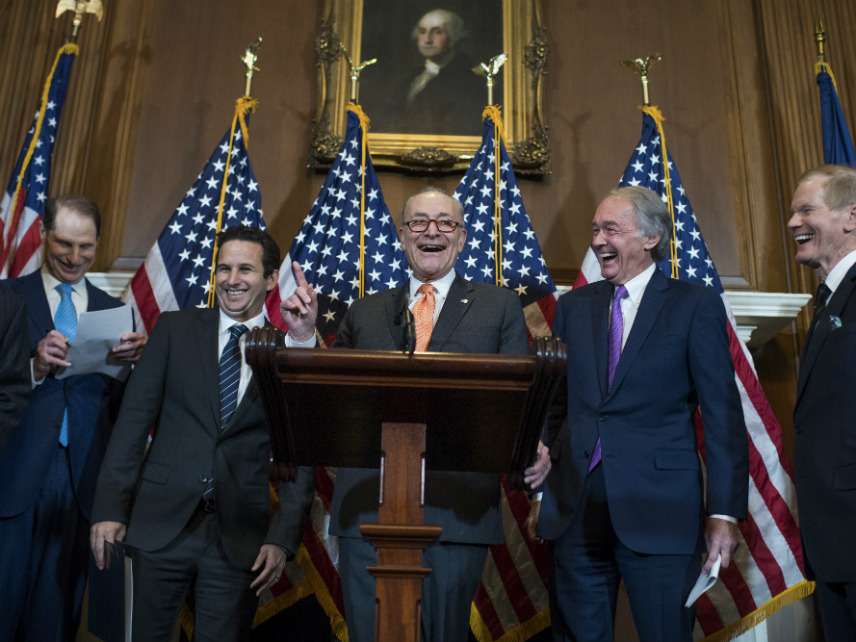

Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) has introduced a resolution to stop the rollback of net neutrality regulations via the Congressional Review Act (CRA), a 1996 law that gave Congress a way to block rules crafted by executive agencies. Little-used for many years, the CRA has recently become a popular way for Republicans to undo regulations they dislike; Markey's bill suggests that the Democrats are watching and learning.

But that doesn't mean their effort will work.

Once a new regulation has been entered in the Federal Register, the CRA gives the Senate 60 days to submit a resolution stopping the rule under an expedited process. In order initiate this process, a CRA requires 30 co-sponsors. Democrats have indeed reached this 30 co-sponsor mark: A full 43 senators have signed on. But that is pretty much all they have.

For starters, the net neutrality rollback announced by the FCC last month has yet even to be entered into the Federal Register, so Democrats currently have no actual rule to review. Getting 30 co-sponsors is for the moment meaningless.

But that will soon change. The more important problem: To pass this resolution Democrats will have to get majority votes in both houses of Congress, each of which is currently Republican-controlled.

Passage in the Senate is conceivable, given that two Republican senators, Susan Collins and John Thune, have said they'd be open to a legislative restoration of net neutrality rules. Collins has even said she would support Markey's bill. But Republicans command a larger majority in the House—and the expedited process allowed in the Senate doesn't apply there. And even if by some miracle enough House Republicans cross party lines to pass the bill, it will still have to be signed by President Donald Trump. That isn't exactly likely.

Given those obstacles, this plan looks less like a serious policy proposal and more like a show for the voters. And that's for the best: The rollback of these rules returns us to the light-touch approach that allowed the internet to grow and thrive. That isn't something to block; it's something to celebrate.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (51)