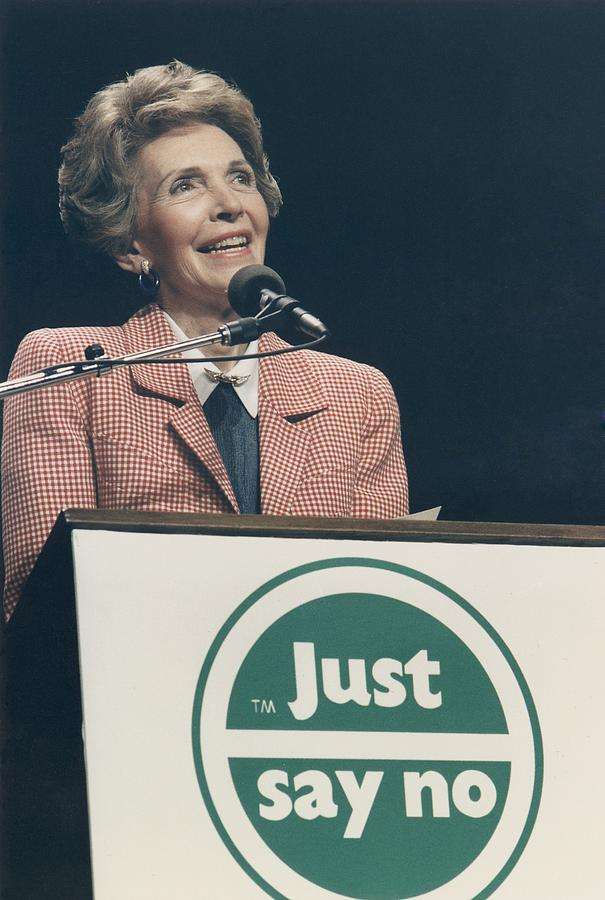

The Darker Side of 'Just Say No'

Nancy Reagan demanded that everyone-not just schoolchildren-parrot her all-or-nothing, black-and-white approach to drugs.

"If you asked anyone in America today what Nancy Reagan does," the first lady's former press secretary, Sheila Tate, told the Associated Press in 1986, "they'd say she was involved in fighting drugs. She owns that issue now….It's what she'll be remembered for."

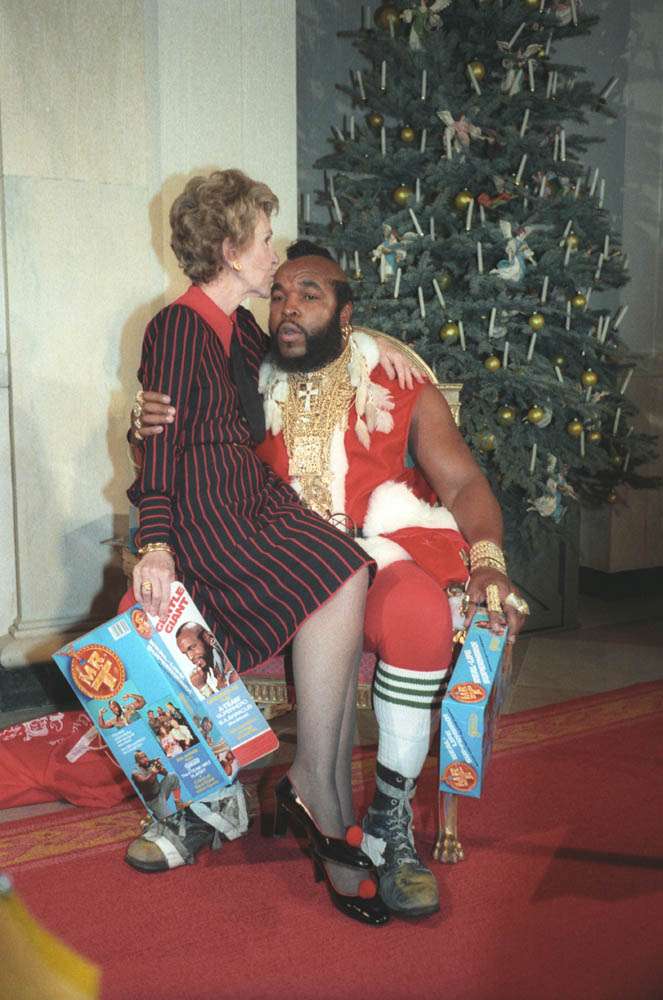

Tate surely was right about that. Lady Bird Johnson had highway beautification, Laura Bush had literacy, and Michelle Obama has fitness. But probably no first lady in history has been as strongly identified with a cause as Nancy Reagan, who died last week. In pursuit of "a drug-free society," she visited schools and treatment centers throughout the country, led thousands of schoolchildren in drug-free pledges, delivered dozens of speeches, gave more than 100 interviews, filmed PSAs with movie stars such as Clint Eastwood, co-hosted Good Morning America, and did cameo appearances on Diff'rent Strokes and Dynasty. She even sat on Mr. T's lap.

"If you even save one life," the first lady liked to say, "it's worth it." But there is no evidence that her crusade saved anyone's life, or even stopped people from using drugs. Although drug use, as measured by government-commissioned surveys, fell during the 1980s, that trend began years before Nancy Reagan launched her "Just Say No" campaign. As the drug policy historian David Musto observed in a 1986 interview with the Los Angeles Times, the first lady was "responding to a shift in attitude toward drugs in the U.S." that was already under way when Ronald Reagan took office. "There is little research to chart the effectiveness of marketing offensives like 'Life Abuse' and 'Just Say No,'" the Times reported in 1988. "But the consensus seems to be that they can't hurt."

Contrary to that consensus, Nancy Reagan's anti-drug activism was not just silly or ineffectual. It was fundamentally misguided, avowedly intolerant, and unabashedly repressive, promoting violence as a response to peaceful activities that violate no one's rights. It reinforced misconceptions about drug use that shaped public policy for decades, leading to millions of unjustified arrests and prison sentences. While I have no doubt that Reagan was genuinely moved by the plight of drug addicts and sincerely motivated by a desire to help children avoid that fate, the policies she supported have hurt a lot of innocent people. Whether she saved lives is doubtful, but she helped ruin many through her influence on her husband and the general public.

According to the 1984 biography Nancy Reagan: The Woman Behind the Man, the first lady's anti-drug crusade grew out of a 1982 exchange with a student at Longfellow Elementary School in Oakland. The girl asked what she should do if someone offered her drugs, and Reagan replied, "Just say no." That offhand remark inspired local activists to start Just Say No clubs, thousands of which were eventually formed across the United States and around the world.

Reagan, who became the honorary chairwoman of the clubs' umbrella organization, the Just Say No Foundation, traveled the country, urging children to do what the group's name said. She held anti-drug rallies at the White House featuring thousands of kids in green "Just Say No" T-shirts screaming "JUST SAY NO!" at the top of their lungs. Kids across the country filled out pledge cards, released "Just Say No" balloons, and wrapped giant red ribbons around their schools.

The basic idea underlying these rituals of abstinence was that kids use drugs because of peer pressure, which can be overcome by what Reagan called "anti-peer" pressure. This tactic of fighting conformity with conformity was reflected in the lyrics of a song used in an anti-drug ad: "You don't have to be part of the crowd. Be who you are, and stand up proud. Say no. Just say no."

The idea that joining mass pledges of abstinence is the best way to be yourself and stand apart from the crowd is rather counterintuitive. It reminds me of that scene in Life of Brian where the accidental messiah of the title tells a throng of followers, "You've got to think for yourselves! You're all individuals!" They reply in unison, "Yes! We're all individuals!"

One problem with this approach is that it exaggerates the prevalence of drug use. According to the Monitoring the Future Study, marijuana use among high school students peaked in 1979, when 51% of seniors reported smoking pot in the previous year. By the early 1980s, that figure had dropped to about 40%, and no doubt it was substantially lower among the younger students who were the targets of Just Say No. "Everybody doesn't do it," Reagan would tell schoolchildren. But if you tell kids saying no requires courage and will make them stand out from the crowd, you are falsely implying that drug use is the norm among their peers, a misimpression that encourages experimentation.

The overemphasis on peer pressure also discounts the real reasons people use drugs. "It's not fun," Reagan insisted, which surely ranks as one of the biggest lies ever told by a first lady. Of course drugs are fun; that is why people like them so much. Anyone who denies this obvious fact instantly loses any credibility on the subject among kids who have any experience with it, whether direct or indirect.

Likewise anyone who insists that all drug use is potentially deadly and refuses to distinguish between casual use and addiction. "You cannot separate so-called polite drug use at a chic party from drug use in a back alley," Reagan wrote in a 1986 Washington Post op-ed piece. "They are morally equal. You cannot separate drug use that 'doesn't hurt anybody' from drug use that kills. They are ethically identical—the only difference is time and luck." She thus denied the reality that the vast majority of illegal drug users, like the vast majority of drinkers, neither become addicted nor cause serious harm to themselves or anyone else.

Reagan, who reprimanded TV and film producers for depicting drug use as anything other than a life-endangering mistake, demanded that everyone—not just schoolchildren—parrot her all-or-nothing, black-and-white approach to drugs. "We must create an atmosphere of intolerance for drug use in this country," she wrote in the Post. "Each of us has an obligation to take an individual stand against drugs. Each of us has a responsibility to be intolerant of drug use anywhere, anytime, by anybody."

Two months later, the first lady appeared on television with her husband, who declared "another war for our freedom," a campaign that would include widespread drug testing, stepped-up interdiction efforts, a dramatic increase in drug arrests, and mandatory minimum sentences—all at a time when illegal drug use was declining. "There's no moral middle ground," Nancy Reagan declared when it was her turn to speak. "Indifference is not an option. We want you to help us create an outspoken intolerance for drug use. For the sake of our children, I implore each of you to be unyielding and inflexible in your opposition to drugs."

Lest you misunderstand, the unyielding and inflexible intolerance Nancy Reagan advocated was not limited to scolding and shunning. "To get serious about stopping illegal drugs," she said in her 1988 speech at the United Nations, "means confronting all those citizens who use drugs." She regretted that "it is often easier to make strong speeches about foreign drug lords or drug smugglers than to arrest a pair of Wall Street investment bankers buying cocaine on their lunch break." She warned that "if we lack the will to fully mobilize the forces of law in our own country to arrest and punish drug users, if we cannot stem the American demand for drugs, then there will be little hope of preventing foreign drug producers from fulfilling that demand." Such a crackdown would be just, she argued, because every drug user is "an accomplice to every criminal act, every murder, every terrorist attack carried out by the narcotics syndicates."

As usual, Reagan ignored the government's role in fostering violence by creating a black market in which there is no legal way to resolve disputes. She dismissed opponents of prohibition as "a few voices on the fringes," saying, "I do not believe the American people will ever allow the legalization of drugs in our country. The consensus against drugs in the United States has never been stronger."

While Reagan spoke, The Washington Post reported, Secretary of State George Shultz "sat directly behind her." When she finished, he "leaned forward and patted her shoulder," while "she reached back and took his hand."

A year later, after he left office, Shultz stopped patting Nancy Reagan's shoulder. "It seems to me we're not really going to get anywhere until we can take the criminality out of the drug business and the incentives for criminality out of it," the MIT-trained economist said in a Wall Street Journal op-ed piece. "Frankly, the only way I can think of to accomplish this is to make it possible for addicts to buy drugs at some regulated place at a price that approximates their cost….We need at least to consider and examine forms of controlled legalization of drugs."

Shultz remains a prominent critic of the war on drugs that Nancy Reagan championed, saying possession of drugs for personal use should be decriminalized. As for "the American people," whose support Reagan took for granted, 58 percent of them think marijuana should be legal, according to the latest Gallup poll, up from 23 percent in 1985. Tolerance seems to be winning, no thanks to Nancy Reagan.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Show Comments (58)