Shorter Crack Sentences Help Reduce Federal Prison Population

After 2010 reforms, crack use fell along with prosecutions and penalties.

Five years ago yesterday, President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act into law, reducing draconian penalties for crack cocaine offenses so they were closer to the penalties for cocaine powder. Since then, according to a new report from the U.S. Sentencing Commission (USSC), the sentencing gap between the two forms of cocaine has narrowed, the number of crack cases prosecuted by the federal government has fallen dramatically, and the the federal prison population has begun to shrink. Meanwhile, crack consumption has continued to decline, and the cooperation rate among crack offenders has not fallen, despite federal prosecutors' warnings that lighter penalties will make defendants less inclined to assist the government.

Prior to the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA), the amount of cocaine powder required to trigger mandatory minimum sentences was 100 times the amount of crack. That disparity had no rational basis, since these are simply two forms of the same drug—one snorted (or injected), the other smoked. The unequal treatment was especially troubling because crack offenders were (and are) overwhelmingly black, so people with dark skin tended to get longer sentences than people with light skin who committed similar (or more serious) crimes. The new weight ratio is 18 to 1 rather than 100 to 1, which is just as arbitrary but not nearly as cruel. Under current law, a dealer gets a five-year mandatory minimum for 28 grams of crack and a 10-year mandatory minimum for 280 grams, as opposed to the old cutoffs of five and 50 grams, respectively. With cocaine powder, 500 grams will get you five years and five kilograms will get you 10.

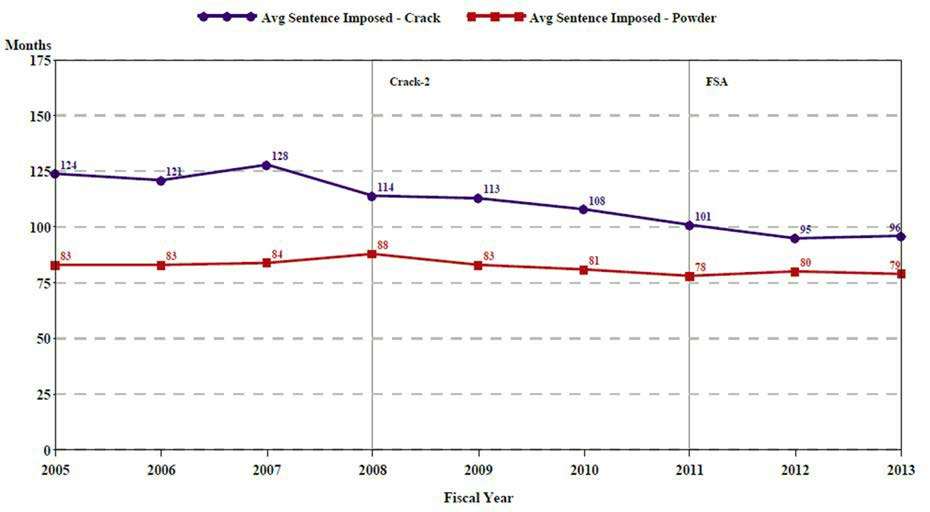

Not surprsingly, the average sentence for crack offenders, which fell after 2007 thanks to revised sentencing guidelines and a series of Supreme Court decisions that gave judges more discretion, fell again after the FSA took effect, from 108 months in 2010 to 96 months in 2014, while the average powder sentence remained about the same (79 months in 2014, compared to 81 months in 2010). At the same time, the number of federal crack sentences fell by half, from 4,730 in 2010 to 2,366 in 2014. During that period about 6,000 crack offenders sentenced after the FSA took effect received shorter prison terms as a result. Their sentences averaged 71 months, compared to 106 months under the old rules. Retroactive changes that the USSC made to its sentencing guidelines in light of the FSA reduced another 6,880 prison terms. The combined effect, according to the commission, is "an approximate savings of 29,653 bed-years to the Bureau of Prisons."

The FSA also eliminated the five-year mandatory minimum for simple possession of crack, a change that had a much smaller impact because such sentences were always rare. The annual number ranged from one to three between 2005 and 2010. There were a total of seven in 2011 and 2012, imposed on people who committed their offenses before the FSA took effect. All seven successfully appealed those sentences on the grounds that the new rules should apply to anyone sentenced after August 3, 2010.

Reduced crack sentences have contributed to a recent decline in the federal prison population, which rose from 24,640 in 1980 to 219,298 in 2013 before dipping to 214,149 last year. According to the National Association of Assistant U.S. Attorneys (NAAUSA), that 2.3 percent drop, following a 790 percent increase, means "our federal prison population is not exploding," which is literally true but rather misleading.

The NAAUSA's position paper, which Scott Shackford discussed here last week, also warns that "slashing minimum mandatory penalties will threaten the prosecution of many of the most dangerous and high level criminals involved in drug trafficking by undermining the cooperation incentive that the current sentencing structure creates." But the sentencing commission found no evidence of such an effect. "Rates of crack cocaine offenders cooperating with law enforcement have not changed despite changes in penalties," the USSC report says. "The rate of sentences that were below the guideline due to a government substantial assistance motion remained stable throughout the 2005-2013 period, indicating that the reductions in penalties during this period did not generally reduce the willingness of offenders to provide assistance to the government in the prosecution of others."

The report debunks another NAAUSA claim: that sentencing reform leads to an "increase in addiction" as drug dealers return to the streets prematurely, luring new users who otherwise would have escaped the bonds of pharmacological slavery. To anyone familiar with the economics of the black market, which replaces dealers as soon as they are arrested as long as there is a demand for their product, that prediction makes little sense. So it is not surprising that self-reported crack consumption, which was already falling when the FSA was enacted, continued to drop along with crack sentences.

Show Comments (41)