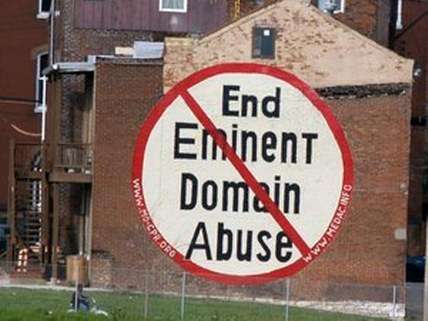

Eminent Domain Abuse is Making a Comeback

As the economy recovers, a rise in eminent domain to favor connected players looms, despite so-called reforms

The use of eminent domain to seize mortgages from investors has been in the news recently. But, because of efforts to rescind protections enacted by state courts and legislatures, we're likely to hear more about traditional eminent domain abuses: the seizure of modest, well-maintained homes and businesses to benefit wealthy, politically connected developers.

Eminent domain abuse has dropped off considerably since its high-water mark in 2005 when, in Kelo v. New London, the Supreme Court ruled that local officials can condemn property solely because they can imagine an alternate use for it that might generate greater tax revenue.

Faced with outraged electorates, legislators in some 45 states have now rewritten their eminent domain laws to protect property owners from grabby local governments, or at least give the appearance of doing so. Some of the most abusive states—Florida, California, and Ohio—have enacted the strongest reforms by statute, initiative, or court ruling.

There is no doubt that the economic downturn played a role by dampening developers' appetites for property. Even in states like New York, which have done precisely nothing to rein in abuse post-Kelo, new takings are rare. But as the economic recovery gains steam, Kelo-style takings threaten to re-emerge.

In March, Alabama reneged on its reforms, which had provided significant protections for property owners. Lawmakers, perhaps inadvertently, included condemnation authority in a statute that expands tax subsidies for industrial parks.

In California, under the guise of promoting "transit-oriented development" and affordable housing, legislators are plotting to revive eminent domain authority for private projects. The effort failed this fall but will be taken up again in January.

A bill in New Jersey (A3615) that would weaken protections for property owners sailed through the legislature, bolstered by support from the New Jersey League of Municipalities and the New Jersey Builders Association. Governor Chris Christie signed it into law last month. According to the bill's authors, the law codifies two state court rulings requiring cities to prove that property is a threat to public health and safety before seizing it and also provide "fair and adequate" notice to property owners when eminent domain is authorized.

In reality, the law attempts to remove the protections proponents say it codifies. "This law is transparently an attempt to go back to the old way of doing business," says Peter Dickson, a New Jersey-based land-use attorney.

For instance, far from demanding cities prove a property is a threat to health and safety, the law says officials need only assert that the property somehow impedes land assembly—a standard that puts virtually every property in the state at risk.

The law also allows for the creation of "non-condemnation redevelopment areas" where officials do not have eminent domain authority—unless a property owner refuses to sell. In the case of such refusal, a non-condemnation area can be transformed into a condemnation area. The intended effect of the provision is to confuse property owners.

"If you're in a non-condemnation area," says Dickson, "you're going to say, 'why should I go hire a lawyer and spend tens of thousands of dollars to challenge this designation if it doesn't put me under eminent domain?'" But failing to challenge the designation within 45 days means you lose the right to challenge it, even if condemnation occurs many years later.

In New London, Connecticut, the site of Kelo, after tens of millions of dollars in public spending, the redevelopment zone is a barren waste. Pfizer Inc., the intended beneficiary of the plan, abandoned the city after its tax incentives expired. "Successful" projects still rely on public subsidies for years after completion, and their contribution to the tax rolls remains debatable at best.

As a new chapter in urban renewal history begins, post-Kelo and post-recession, there is some cause for optimism. People across the political spectrum despise eminent domain abuse. And, when legislators have yielded to powerful interests, state courts are increasingly skeptical of calling private development a public use. But without effective safeguards, this chapter may look suspiciously like the last.

Show Comments (21)