Unlearning History

Three decades after Massachusetts ended its disastrous experiment with rent control, voters are considering giving the policy another shot.

Happy Tuesday, and welcome to another edition of Rent Free.

This week's newsletter takes a look at the bad idea in housing policy that never seems to die: rent control.

In Massachusetts, housing activists, with the support of labor unions, are in the process of qualifying a petition for the November 2026 ballot that would impose a statewide 5 percent cap on rent increases on almost all rental units.

Massachusetts has a multistep process for qualifying citizen-initiated petitions for the ballot. We won't know whether voters will get a chance to vote on this particular policy until the summer.

Rent Free Newsletter by Christian Britschgi. Get more of Christian's urban regulation, development, and zoning coverage.

Yet, initial polling and the speed at which organizers were able to collect signatures suggest there's a lot of popular momentum behind it.

The apparent popularity of this initiative is lamentable for three reasons.

Firstly, the design of Massachusetts' proposed policy would make it one of the more punishing rent control regimes in the country. If passed, one would expect it to negatively impact both housing production and housing quality.

Secondly, the potential revival of rent control in Massachusetts shows that the lessons of history are being unlearned.

From 1970 to 1994, the state gave larger municipalities carte blanche to adopt their own rent control policies.

Several cities jumped at the opportunity with predictably disastrous results. By the time that voters approved an initiative banning rent control in 1994, most of the localities that had passed rent control policies had either repealed them or watered them down significantly.

Despite the well-documented upsides of the 1994 repeal, voters now appear willing to give this failed policy another go.

Lastly, the momentum behind the proposed Massachusetts initiative suggests a general pessimism about the ability of high-cost liberal states to solve their self-imposed housing cost crises.

Out-of-control housing prices have made voters impatient, if not completely cynical, with the idea of bringing prices back down through repealing regulatory obstacles to new housing supply. They want immediate action in the form of price controls, even if those price controls destroy the new production.

While 2025 was a banner year for zoning reform, the specter of a rent control revival should make supply-siders worried about the direction of housing policy in the new year.

The Petition

Beginning this past summer, activists organized under the progressive group Homes for All started collecting signatures for a ballot initiative that would impose a statewide cap on rent increases of either 5 percent or annual inflation as measured by the consumer price index, whichever is lower.

That cap would apply to almost all rental units, with a few exceptions.

Short-term rental units, on-campus dorms, and owner-occupied buildings with four or fewer units would be exempt from the caps. Units in buildings that are less than 10 years old would also be exempt.

Taken together, this proposed policy combines the strictest elements of both legacy rent control laws of the 1970s (which some Massachusetts municipalities used to have and are still on the books in some major cities) and the new generation of statewide rent control laws covering the West Coast.

Those legacy rent control laws typically allow rent increases of a few percentage points per year while completely exempting housing built after the enactment of the law.

Newer statewide rent control policies adopted by Washington, Oregon, and California in the past several years allow for more generous maximum rent increases of 10 percent per year. Those states' laws do apply those rent caps to new construction starting 15 years after they receive their first certificate of occupancy.

Massachusetts' proposed law would keep the lower rent caps of the legacy rent control laws. Like the newer policies, it would apply those rent caps to new construction, while providing a shorter post-construction exemption period.

More significantly still, the proposed Massachusetts law does not allow for vacancy decontrol, whereby landlords can raise rents to market levels when an old tenant moves out and a new one moves in.

Thus, the proposed Massachusetts law seems tailor-made to exacerbate all the downsides of rent control the state experienced during its last experiment with the policy, plus a few more.

The Research

Basic economic theory suggests that capping rents below market rates will reduce the quality and quantity of rental housing.

Massachusetts municipalities' own history of imposing and then repealing rent control provides a wealth of empirical evidence to back up the textbook theory.

In 1970, the Massachusetts Legislature passed the Rent Control Enabling Act, which allowed cities with populations above 50,000 to regulate rent increases on existing rental housing.

The cities of Boston, Brookline, Lynn, Somerville, and Cambridge quickly adopted strict rent controls in response. The former four cities either repealed their policies after a few years or moderated them by, as in the case of Boston, adopting vacancy decontrol.

Only Cambridge maintained strict rent controls until 1994, when state voters narrowly approved a ballot initiative banning rent control.

The city's policy exempted buildings constructed after 1969 but did not allow vacancy decontrol. Annual allowable rent increases were typically set between 1 percent to 3 percent per year.

Researchers have since exploited the sudden repeal of Cambridge's rent control law to tease out the effects of the policy.

An early 2003 study by Henry O. Pollakowski, a housing economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, found that the repeal of Cambridge's rent control policy led to a 20 percent increase in housing investment "over what would have been the case if rent control had been maintained." This resulted in a significant increase in housing quality.

A more comprehensive 2007 study by Brigham Young University economist David Sims highlights the stark tradeoffs imposed by Cambridge's rent control law.

On the one hand, Sims' study found that the policy "reduced rents substantially." Rent-controlled units rented for as much as 40 percent less than nearby noncontrolled units. The repeal of rent control resulted in higher rents and significant tenant turnover.

But these benefits came with steep costs for housing quality. Sims' study found that "chronic maintenance problems—such as holes in walls or floors, chipped or peeling paint, and loose railings—were more prevalent in controlled than in noncontrolled units during the rent control era and that this differential fell substantially with rent control's elimination."

He also found that rent controls encouraged owners to move their units off the rental market.

Sims' study found no impact of rent control on new housing construction. That's largely to be expected as the policy did not apply to new construction.

Another major study of the effects of rent control repeal published in 2014 by MIT economists David Autor, Christopher Palmer, and Parag Pathak found that the repeal of rent control caused a massive increase in the values of both rent-controlled and non-rent-controlled properties.

The increased valuation of rent-controlled properties after the 1994 decontrol is evidence that rent control lowered rents for incumbent tenants. Building values were suppressed because the rents that could be charged on them were also suppressed.

And yet, the authors of the 2014 study write that "the efficiency cost of Cambridge's rent control policy was large relative to the size of the transfer to renters."

The bulk of the increase in Cambridge property values post-decontrol happened at neighboring properties that were not subject to rent control.

Autor, Palmer, and Pathak argue that this is because rent control led to an inefficient allocation of apartments. Rent-controlled tenants were encouraged to hang on to larger units for longer. Price caps prevented tenant turnover that would have brought in new, higher-income renters.

This all suppressed the production of local amenities that raise property values. Autor, Palmer, and Pathak write that the repeal of rent control "led to changes in the attributes of Cambridge residents and the production of other localized amenities that made Cambridge a more desirable place to live."

Since local Massachusetts rent control policies did not apply to new construction, they don't tell us a lot about the impacts of rent regulation on housing production.

But plenty of other research finds that the effect is negative. One study published in June 2025 in the Journal of Housing Economics that looked at the effects of rent control across the United States from 2000 to 2021 found that these policies are associated with a 10 percent reduction in the total number of housing units.

The Politics

One can look at the Massachusetts research and see why rent control would have some enduring appeal. On the most basic level, the policy does what it says on the tin.

Over time, it lowers rents for incumbent tenants below what they'd be charged in the market. That creates "stability" as lower-income tenants who would have been priced out by rising rents can stay in their units for longer.

But the costs of providing these benefits are steep. Lower rents are purchased with lower-quality units. Stability for incumbents means inaccessibility for newcomers and overall neighborhood stagnation.

Assuming price controls work the same in the 2020s as they did in the 1970s, we can anticipate these same results should Massachusetts re-impose rent control.

Because activists' proposed policy would also apply rent control to new construction (after that 10-year exemption), one would assume an additional cost to new housing production.

The severity of the proposed rent control law likely explains Massachusetts politicians' trepidations about supporting the ballot initiative.

Gov. Maura Healey, a Democrat, has already said that she opposes the petition.

Boston Mayor Michelle Wu, otherwise a supporter of rent control, has been non-committal. She said back in August that the petition's particulars are not what she'd want to see in Boston. Wu has yet to say whether she supports the ballot initiative or not.

Commonwealth Beacon quotes a number of progressive legislators who are reluctantly supporting the petition, while saying that a more modest proposal that simply gives cities the right to adopt their own rent control policies would be an easier sell to voters.

The electoral record of rent control ballot initiatives elsewhere in the country is mixed.

California rent control advocates have tried three times in the past six years to pass some version of a statewide rent control ballot initiative and have lost by a landslide each time.

But voters have passed city-level rent control policies in St. Paul, Minnesota, Portland, Maine, and a number of California municipalities.

And the general idea of rent control remains popular. Since 2019, three state legislatures (Washington, Oregon, and California) have all passed rent control policies. New York City voters just elected a mayor whose signature campaign policy was to "freeze the rent."

The organizers behind Massachusetts' rent control petition needed to gather 74,574 signatures by early December to start the ballot initiative process. They turned in some 124,000. The state Elections Division eventually certified 88,132 of those signatures, the most of any of the five proposed ballot initiatives that have had their signatures certified.

A November poll of registered voters found 60 percent support for the rent control petition.

With the initial signatures now gathered and certified, the proposed rent control law will be considered by the state Legislature, which has until May to pass it. If lawmakers don't pass the policy as proposed, organizers have to collect an additional 12,429 signatures by mid-July to secure a spot on the November 2026 ballot.

A Bad Problem

The notion that Massachusetts has a housing cost crisis should be pretty uncontroversial. Whether it's average rents, home prices, or home price–to-income ratios, the Boston area ranks as one of the least affordable metros in the country.

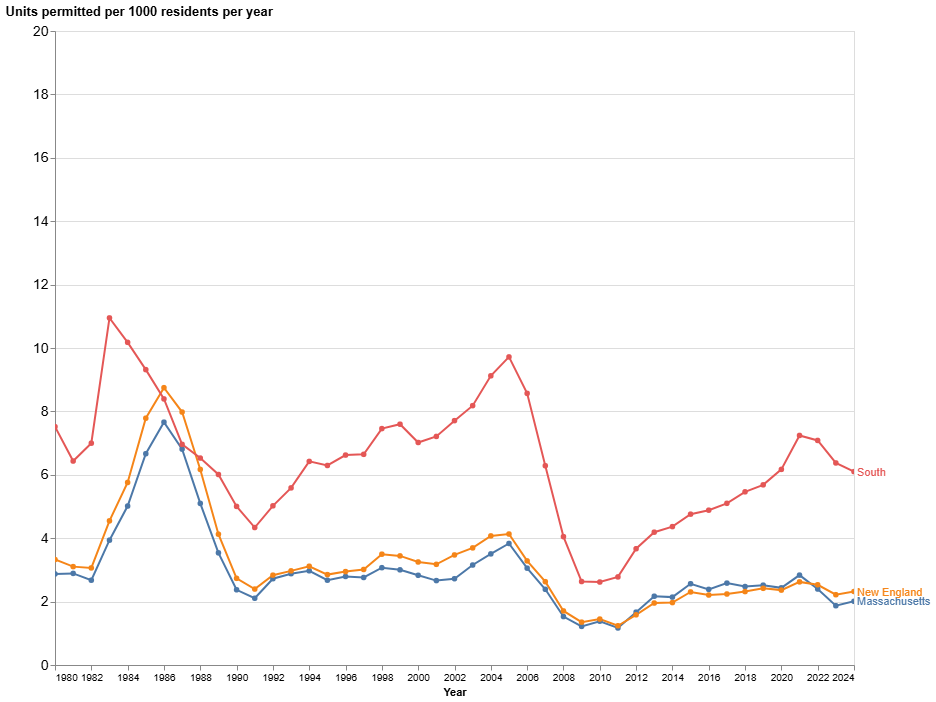

On the production front, the state is building two units per 1,000 residents. That's slightly less per capita production than New England (generally a low building region) and about a third of the production in the booming South.

Housing unaffordability in Massachusetts is a serious problem. It's also a bad problem in that, as housing affordability gets worse, the political prospects of fixing the problem also get worse.

As housing prices go higher, more and more market-rate renters and aspiring homeowners decide to leave the state entirely and move to more affordable environs.

In other words, the population of people who'd benefit the most from supply-side reforms that would sustainably bring housing costs down shrinks by the day.

The people left behind are increasingly those insulated in some way from rising costs; either they already own their home, their incomes are high enough to weather high market prices, or they benefit from government subsidies of one kind or another.

That's a bad enough political dynamic. Worse still is the fact that decades of housing underproduction under the state's heavily regulated land use regime have made voters cynical about the ability of new supply to meaningfully bring housing costs down.

When your state builds very little housing, the housing that is built is generally very expensive. Your average cost-burdened renter can be forgiven for looking at the high prices of new construction and not believing that allowing more of it will make housing more affordable for them.

It's no wonder then that rent control, in all its seductive simplicity, is making a comeback.

That Massachusetts has managed to pass any supply-side reforms in this context is remarkable. In 2021, the state passed the MBTA Communities Act, which requires localities to upzone land near transit stops. This year, Cambridge passed a robust "middle housing" policy.

But as productive as these reforms might be, they are still, all things considered, relatively modest zoning liberalizations.

The MBTA Communities Law, like many state-level upzoning mandates, gives localities a lot of wiggle room to undermine the practical effect of the law. The state has sued some localities that refused to implement it.

This is not unlike the situation in high-cost liberal states, particularly California and New York, where costs are high, and the politics of productive reform are always a halting, uphill battle.

Perhaps the one thing Massachusetts really has going for it is that it does not currently have rent control. In addition to the practical benefits of banning this policy, renters in the state are more exposed to rising market rents.

On the margins, that plausibly leads more people to support supply-side solutions to bring market rents down.

Should Massachusetts' proposed ballot initiative pass, one would expect all the practical downsides of rent control in terms of reduced housing quality and quantity to return. Politically, even fewer renters would have any immediate incentive to rally around zoning reform.

The state's bad problem would become a truly intractable one.

Quick Links

- In the latest print issue of Reason, I have an article looking at some of the positive things that incoming New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani has said about zoning deregulation.

- Over at The Argument, Jerusalem Demsas has a fun piece detailing the inherent NIMBYism of Hallmark Christmas movies. Regrettably, it's not just the Hallmark movies. Hollywood films generally favor plots where the NIMBYs ("not in my backyard") are the good guys.

- HousingWire declares 2025 the year of housing market normalization. Inventory increased, price growth flattened, and homes took longer to sell.

- The Trump administration has promised a major housing reform initiative in the new year, while offering few details on what exactly it might propose.

- Real rents fell nationwide in 2025, following a banner year for multifamily construction in 2024.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (25)