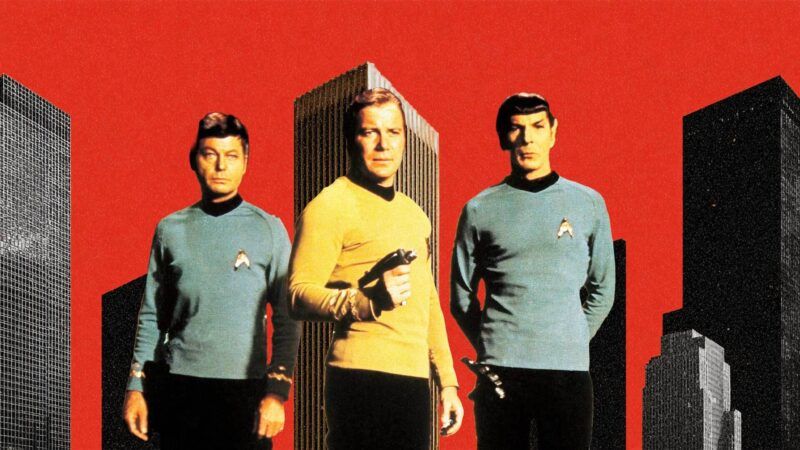

Would Star Trek's Transporter Destroy Cities or Save Them?

What a speculative technology can tell us about the demands for urban density and sprawl

Happy Tuesday, and welcome to another edition of Rent Free.

Given the holiday slowdown in the news and general merriment that comes with the Christmas season, I'm hoping readers might indulge me in writing this week's newsletter on something a little more fun and speculative.

That would be the urban form of the Star Trek universe.

Every once in and while on social media, a person will post a screenshot of the San Francisco Bay Area of the 23rd or 24th century, as imagined by the various Star Trek movies and TV shows.

Lo and behold, it's massively more built up in the future than it is today.

the world of star trek is only prosperous because of their willingness to boldly develop at high densities where no was allowed to before pic.twitter.com/cPuAKFOEpL

— Matthew Zeitlin (@MattZeitlin) December 1, 2020

Since the Venn diagram overlap between Star Trek fans and YIMBYs ("yes in my backyard") is close to a flat circle, this is always presented as a positive thing.

Star Trek generally presents a positive, progressive vision of the future. A bunch of skyscrapers towering over Marin County—currently a low-density, tightly zoned hotbed of NIMBYism ("not in my backyard")—is just more evidence that the good guys won.

While I certainly like the idea that a YIMBY victory in Marin County is Star Trek canon, I have to confess that I do wonder just how realistic it is.

Rent Free Newsletter by Christian Britschgi. Get more of Christian's urban regulation, development, and zoning coverage.

Specifically, in a universe where physical travel is instantaneous and production of most household goods can happen within the home, would people still even want to live next to each other?

It might seem silly to spend a whole newsletter puzzling about the impact of a fictitious technology on far-future cities. Then again, a major purpose of science fiction, beyond pure entertainment, is precisely to examine these questions.

Whether it's the rise of remote work, the advent of driverless cars, or ubiquitous drone deliveries, cities in the mid–21st century are likely to experience a lot of technology-driven changes.

Serious thinkers and researchers are already hard at work trying to puzzle out what all this means for urban economies and the built environment. I can't hope to replicate those efforts.

But I do think that looking at how we might live in a world where there's a replicated chicken in every pot, and a transporter in every garage, could tell us a lot about where cities are headed as we barrel into these next decades.

So, engage.

A Final Urban Frontier

It's beyond conventional in science fiction for cities to be depicted as ultra-dense conglomerations of buildings and people.

Whether it's Star Wars or Blade Runner, everyone is packed in together. The only major difference is whether this urban form is depicted as a gleaming utopia or an environmentally ruined hellscape. Sunny, positive Star Trek is definitely in the former category.

Yet there's good reason to think that cities of even modern American densities would not exist in the Star Trek universe, thanks to the famous transporter.

Anyone who's seen the various TV shows or movies will know that people in Star Trek generally get around primarily by using the transporter to beam instantaneously from one point to another. Even if you've never seen a second of Star Trek, you still will probably know the phrase "Beam me up, Scotty"—effectively the 23rd century equivalent of calling an Uber.

One would expect this technology to completely revolutionize the built environment.

Unless a dictatorial government is calling the shots, there's arguably nothing more consequential for what form cities take than the dominant transportation technology people use.

The past century or so of urban development has taught us that the faster the dominant transportation technology is, the more likely cities are to sprawl.

Readers might be familiar with Marchetti's constant, which states that people are usually only willing to commute 30 minutes one way between work and home.

In the days when most people were limited to walking or riding, this meant that cities were usually really small, cramped places.

The first early urban rail systems allowed people to live further from city centers, where land was cheap, and they could afford more private space. Cars supercharged the expansion of urban areas. By enabling not just faster travel but point-to-point travel, they also coaxed a lot of jobs out of city centers.

There's a very active debate about just how much post-war urban sprawl, and the consequent population declines of city centers, was the result of government interventions like federal highway funding, "urban renewal," single-family zoning, mortgage subsidies, and whatever else.

The fact that the center of an urban area still provided access to the most jobs and locations within a given travel time meant that there was still demand for high densities downtown.

Nevertheless, faster, point-to-point transportation still favored sprawl. Absent any government interventions, the car was going to ensure that urban areas grew outward a lot.

In Search of Sprawl

At first blush, one would assume that the effect of the Star Trek transporter on the urban form would basically be the effect of the car to the nth degree.

A technology that provides not just rapid but instantaneous travel would seem to be the Platonic ideal of a sprawl-spurring technology.

According to Star Trek technical manuals prepared for the original show, transporters had a range of 40,000 kilometers. That's roughly the circumference of the Earth.

That means someone with a transporter in their home would presumably be able to commute anywhere on the surface of the Earth in seconds.

Today, the tradeoff of urban life is that one has more proximity to jobs, people, and amenities at the expense of less private space. Lots of people living next to each other drives up land prices. Higher-density development also costs more to construct.

Even without zoning and all the other red tape raising the expense of urban development, the cost of occupying a square foot in a dense city center is just going to cost more.

With a transporter, however, one could seemingly eliminate the tradeoff between private space and access to amenities and jobs.

Being able to beam from your living room to any other location on the planet could enable you to live on a remote island or in the middle of the desert and still make it in to work on time, or visit friends or family at your leisure.

If that's the case, why wouldn't everyone choose to buy a bunch of cheap land in the middle of nowhere, put up a castle on it, and call it a day?

We've seen much lower-tech versions of this exact thing. During the 20th century, wave after wave of urbanites have decamped for suburban and exurban areas, where land and housing are cheaper.

During the pandemic, we saw the rise of "Zoom towns" where newly remote workers transported their city jobs and city incomes to smaller communities, where housing is less expensive.

Add in Star Trek's replicator—which can make almost any household good right there in your home—and one wouldn't even need a corner store to shop at.

Does that mean that Gene Roddenberry's imagined utopia would be a sprawling suburban utopia too? In his universe, would skyscrapers be as obsolete as money?

Maybe, but maybe not.

The Next Generation of Density

If you've watched as much Star Trek: The Next Generation as I have, you'll notice that the characters spend a lot of their time traveling across star systems to attend diplomatic summits, professional conferences, and other missions that really could have been an email (or communicator conversation).

Even on the Enterprise itself, where one would assume the goal is to use square footage as efficiently as possible, ample amounts of space are devoted to conference rooms, theaters, and even a bar that isn't strictly necessary.

Clearly people in the Star Trek universe value face-to-face interactions. That's cause to believe they would value urban density as well, even if transporters make it theoretically obsolete.

It's a quirk of our modern economy that plenty of jobs that could be done remotely benefit the most from having people in the same room and the same city together.

As Harvard urban economist Edward Glaeser wrote in a March 2020 working paper, "urban density abets knowledge accumulation and creativity. Dense environments facilitate random personal interactions that can create serendipitous flows of knowledge and collaborative creativity."

Most jobs in the finance, tech, and publishing industries could all be done from the comfort of one's home. These industries are nevertheless highly concentrated in America's densest, most expensive cities.

Indeed, growth in these industries is a major driver of the revivals of urban populations in the mid and late 2010s.

Workers and firms wouldn't be paying a premium to live in the big city if it didn't benefit them somehow. A la Glaeser, they think that physical proximity boosts productivity and makes professional collaboration easier.

The pandemic proved that many jobs could be done remotely. Companies' return-to-office drives over the past several years show that employers think in-person work gets more done.

Zoom towns might have boomed during the pandemic. But big cities that people fled during COVID are starting to fill back up again as well.

If the so-called "death of distance" created by today's communication technology hasn't caused a death of density, one could assume that Star Trek's transporter wouldn't either.

People would still demand office space, coffee shops, bars, and other third places.

With this technology, these wouldn't necessarily all need to be right next to each other. But we could assume that walkability and pleasant streetscapes would still be prized in the far future, too.

It's still nice to walk to the café, even if you don't strictly have to.

Far from making density obsolete, transporter technology might make it a lot more viable.

Cars drive sprawl because they can travel point-to-point farther and faster. They also drive sprawl because their speed necessitates a lot of space. They also need to be stored wherever they end up, necessitating lots and lots of parking spaces.

The Parking Reform Network estimates that parking spaces take up as much as a quarter to a third of all surface land in many American cities' downtowns.

The upshot is that the more space that's devoted to roadways and parking, the further apart the destinations people are driving to must be. There's a tradeoff between easy car travel in urban areas and dense walkable streetscapes.

While NIMBY complaints about parking and traffic are often overdone, it is true that when most people drive, new businesses and apartments mean more car traffic on a fixed supply of roads.

With transporter technology, one could completely eliminate this tradeoff between fast travel and desirable destinations. One of the primary externalities of density (traffic) would be gone.

Today's clogged streets could be converted to pedestrian malls. Parking lots could be redeveloped into usable businesses and offices without any loss of mobility. Dense areas could become denser, and a lot nicer too.

The Best of Both Worlds

When researchers model the effects of driverless cars on urban density, they find mixed results. The easier commutes created by autonomous vehicles encourage a lot of sprawl. By reducing demand for parking, they would also drive a lot of infill development.

One would imagine Star Trek's transporter technology would likewise hypercharge (warp-drive?) both urban sprawl and urban density, while making both much more livable.

When commuting anywhere is as easy as stepping out your front door, most people would opt to live in remote areas where space, quiet, and privacy are abundant, but rural isolation is a thing of the past.

Without the need for busy arterials and highways, this sprawl would be a lot more pleasant than today's greenfield development.

When they do step out their front door, odds are the destination will be a dense, dynamic urban area freed from through traffic and parking lots.

In this incredibly speculative analysis, one would assume that residential density would decline substantially, but commercial densities in downtowns would explode.

It's canon in Star Trek that Marin County becomes the center for a lot of Federation and Starfleet facilities. That would realistically explain the densities we see there in the shows and movies.

At its best and most wholesome, Star Trek is about people of different backgrounds using technology to solve hard problems. From what we know of the built environment of future Earth, it appears they've done just that for today's urban problems.

Extreme sprawl and density co-exist without the tradeoffs necessitated by today's technology. All things considered, it's not an incredibly plausible vision of the future. But it is one to strive for nonetheless.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (59)