Lindy-Hopping Nazis and Golems With Guns: The Return of Thomas Pynchon

In Shadow Ticket, characters are forever finding refuge in the folds of the map.

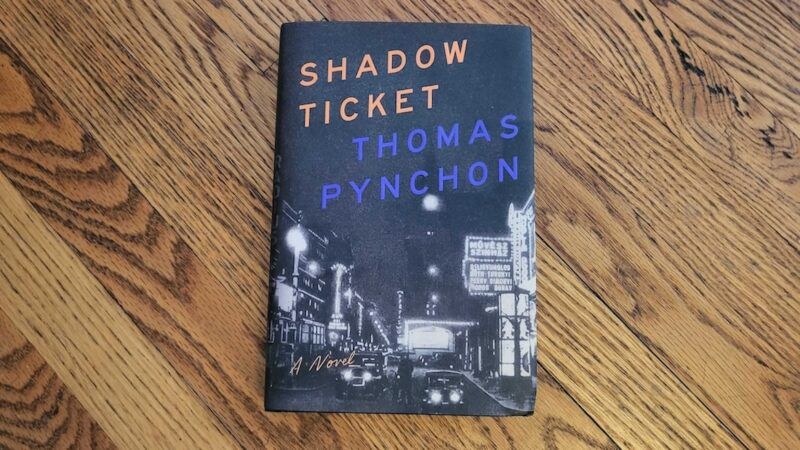

Shadow Ticket: A Novel, by Thomas Pynchon, Penguin Press, 293 pages, $30

My favorite story about Thomas Pynchon, which may or may not be completely true: When Timothy Leary found himself in the hole at Sandstone Federal Prison, the defrocked Harvard doc asked a guard for something to read and the screw tossed a copy of Gravity's Rainbow into the cell. Would a random prison guard really have that book at the ready? Beats me, but I love the image of someone trapped in a tiny room with Pynchon's difficult, funny, endlessly digressive novel as his only escape hatch. There's a photo floating around the internet of Leary's marked-up copy of the book (sometimes misidentified as Neil Armstrong's copy, which makes a different sort of crazy sense). Leary's notes certainly look like things you might scrawl if you're being driven mad simultaneously by solitary confinement and by Pynchon's sprawling universe.

There is often a scent of madness around Thomas Pynchon's fan base, and I say that as someone who has been one of those fans for around 40 years. The man has a reputation in some quarters as an unapproachable writer rarely read outside the academy, but the Pynchon cultists I encounter are more likely to be eccentric autodidacts prone to building elaborately strange mental models of the world. I have run across but cannot find again a small online subculture whose devotees combined the tenets of Marxism-Leninism with esoteric conspiracy theories about elite occultist pedophile rings; they regarded almost every prominent countercultural figure with suspicion but seemed to revere Pynchon as a prophet. They were the purest form of Pynchon fans: the kind who could be Pynchon characters. I imagine him dropping them into a novel as an aside, maybe in the middle of a list of terror cells or of rival gangs of mathematicians.

But now a door has materialized between the author and the mainstream. Paul Thomas Anderson's impressive film One Battle After Another, based very loosely on Pynchon's 1990 book Vineland, hit No. 1 at the U.S. box office in late September, giving the writer an opportunity to pick up new readers. Almost immediately afterward, a fresh product appeared for those newcomers to buy: Pynchon's ninth novel, an acid noir titled Shadow Ticket. This one offers the writer in a relatively accessible mode. There are no dense passages that stretch on for pages, no detours into literal rocket science, no homoerotic encounters with Malcolm X. It's short, it's funny, and its core plot—private eye chases runaway dame—is familiar enough to give a cautious reader something to cling to as the book gets stranger.

It does get plenty strange. It is one thing to say the novel is about a strikebreaker turned detective in 1930s Milwaukee who gets hired to track down a cheese heiress and finds himself traveling through central Europe against a backdrop of rising fascism. But that bare-bones sketch won't prepare you for a story that also includes a dog piloting an autogyro, an unsurrendered Austro-Hungarian submarine lurking about Lake Michigan, a bowling alley where Nazi dancers Lindy-hop to a swing version of the "Horst Wessel Song," and a golem whose left arm doubles as "a modified ZB-26 Czech light machine gun." This is the sort of book that casually invokes "a secret Indian reservation, mentioned only once in a rider to a phantom treaty kept in a deep vault under a distant mountain belonging to the U.S. Interior Department and unrevealed even to those guarding it." It has vast conspiracies, encounters with the supernatural, and a development near the end that reveals we've tumbled into an alternate historical timeline.

For all that, the book is not some Permanently Wacky Zone that is never anything but absurd and strange. Gravity's Rainbow isn't all aerial pie fights and octopus attacks, after all; it has sequences, like an Advent service in wartime Kent, that are genuinely moving. While nothing in Shadow Ticket is as affecting as that Christmas Eve scene, the book has an emotional core to it. Among the characters traversing its surreal labyrinths, you'll find some three-dimensional beings capable of disappointment and love.

And just as Gravity's Rainbow deals with serious political ideas, so too does Shadow Ticket. Its 1930s setting makes that inevitable: Fascists are lurking in Europe (and Wisconsin), the persecution of Jews is starting to pick up, and the left isn't exactly incapable of authoritarian ugliness either. (Besides an inevitable allusion to Stalin, the book periodically brings up Béla Kun's short-lived 1919 communist dictatorship in Hungary, which is damned here not just for its own predations but for teaching lessons in persecution to the paramilitary antisemites who came along later. The Tankie Esotericists might not care for those parts.) There are no tedious efforts to make everything match up one-to-one with contemporary politics, but there are certainly moments when the fiction feels familiar. At one point, a man grumbles that "there used to be more time to make a getaway. Now they're flashing everybody's mug shot all around the world in the blink of an eye, pretty soon there's no place to run to anymore…"

Not that this is a totally surveilled society. The book's characters are forever finding refuge in the folds of the map, from that secret Indian reservation to that unsurrendered submarine. (The latter resurfaces later, far from the Great Lakes, rescuing people from death squads.) Nor is it just the congenial characters who seek refuge. A cheese syndicate becomes "more global and sinister in scope" by "avoiding central headquarters, instead choosing a more distributed model, free-zone hopping, setting up shop in short-lived entities emerging from the World War and the Russian Revolution, preferring mixed populations, disputed territories, histories of plebiscites and provisional government, currencies printed on inexpensive stock in fugitive inks."

One of those places is Fiume, a then-Italian, now-Croatian city that briefly became independent when the poet-soldier Gabriele D'Annunzio seized it after World War I. During that autonomous interval, Pynchon reports, the place "had a reputation as a party town, fun-seekers converging from all over, whoopee of many persuasions, wide open to nudists, vegetarians, coke snorters, tricksters, pirates and runners of contraband, orgy-goers, fighters of after-dark hand-grenade duels, astounders of the bourgeoisie." In his 1991 tract T.A.Z., the anarchist writer Hakim Bey described Fiume in similar terms, presenting it as an anti-authoritarian festival that briefly blipped onto and off of the map. I'd wager that Pynchon, whose books are peppered with anarchists, has read that. But Pynchon also surely knows that D'Annunzio had an authoritarian side, inventing public rituals that would later be adopted almost wholesale by Benito Mussolini. In our world, as in Pynchon's, even an apparently free zone can feed into something antithetical to freedom.

Shadow Ticket is eminently quotable, and I could probably lay down another couple thousand words relaying good lines ("If you happen to be a spy, one big selling point about Vienna is there are no laws against spying, as long as the spying isn't on Austria") or describing amusing scenes (when "the Al Capone of cheese" meets the actual Al Capone, he asks what Capone is the Al Capone of). But at some point I'd just be retyping the book, and who needs that? Better to go straight to the source.

And to savor it. Pynchon is 88 years old, and this might be the last novel he'll publish in his lifetime. Though who knows? The man was working on Mason & Dixon while he was also writing Vineland. Maybe he doubled up this time too, and Shadow Ticket is an aperitif for another 10-course psychedelic feast—the sort of book you'd like to have handy in solitary confinement or a space capsule.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Since when was Hitler's National Socialist party right wing?

A few decades of liberal miseducation and it becomes a fact.

In fictional writing.

I also enjoyed the pretentious not so subtle dig of "why would a prison guard have that book?"

Yes we know Jesse you are so much smarter than all of us plebs...at least in your own mind

Beta jesse*

I also enjoyed the pretentious not so subtle dig of "why would a prison guard have that book?"

I of course said nothing about whether the book belonged to the guard or whether the guard had been reading it.

Timothy Leary has a history of embellishing his anecdotes, and I am not sure this story went down exactly as he described it in his autobiography, with a random guard in Minnesota just happening to have a copy handy of a book that's stuffed with Leary's obsessions. But maybe it did. As I said in the article: "Beats me."

"Would a random prison guard really have that book at the ready? "

Thank you for quoting the line accurately this time. I'm not sure why you didn't add "You're right, that doesn't say anything about whether the book belonged to the guard or whether he was reading it," but I'll just assume you left that out by accident.

You clearly have never read the book Gravity's Rainbow.

Jesse might as well have written, "why would a random prison guard have a book on advanced quantum mechanics?" Sure it's possible but not likely. Same kind of idea as Gravity's Rainbow.

I think because hey were mean to gays...

However, they were mean to Jews and given late-stage center left liberalism, that puts the National Socialists squarely in the camp of the left... again.

Team MAGA: The Nazis were left-wing, dummy!

Also Team MAGA: I'm outraged at Bad Bunny being picked for the Superbowl halftime show! Why couldn't they have picked an American performer?

I had to google both of these things to know what you were talking about. Superbowl? "Bad Bunny"?

Since the 1920s, but too many American right-wingers are so scared - wrongly - of the association, and being incapable of an intellectual defence of their own non-extreme position, they pretend that the "Socialism" part means that the Nazis were socialists (just as North Korea is and East Germany was democratic).

It's one of the tells of US political moronism, like claiming that the Democrats are the party of slavery, or that rent control works.

n, they pretend that the "Socialism" part means that the Nazis were socialists

They were socialists. It doesn't mean they were rainbow flag waving tranny-supporting liberals, but they were absolutely socialists.

but they were absolutely socialists.

Except they weren't because they wanted - and got - the support of industrialists and wealthy conservatives. To the extent they seized the means of production, it was to transfer companies from Jewish ownership to German ownership.

They were no more socialist than the average Republican president willing to pay for infrastructure projects and to increase the spending going to the defence indusry.

"and the left isn't exactly incapable of authoritarian ugliness either."

Ya don' say...

A brief nod, a hat tip if you will, that it sometimes, although incredibly rare happens on the rarest of occasions. It's been seen, but rarely photographed. It's damn near a Sasquatch.

Thomas Pynchon; didn’t read

When the TV series V was to come out, I thought, "Oh, no, how could they adapt that? I couldn't even finish reading it!"

The book you want in solitary confinement or on a long journey is war and peace. Just ask Lieutenant Colonel John Sheppard.

Or pen a book about one’s struggles like some left-wing Austrian painter once did while incarcerated.

I like to think of Hitler as an erstwhile Cop City protester.

Proto-antifa

I thought you were going for the gulag aparchigo

If anyone wants an entertaining movie adaptation from a Thomas Pynchon book, I'd strongly recommend Inherent Vice with Joaquin Phoenix.

Edit: I believe it might be streaming on Amazon Prime this month. But I'm too lazy to check.