One Battle After Another Lets Leftist Radicals Off the Hook

A fascinating, frustrating film that plays to the sympathies of liberal Hollywood. It's sure to win a lot of awards.

If you're the betting type, you might as well put everything you've got on One Battle After Another to win big at this year's Oscars. That's not necessarily an endorsement, given the Academy Awards' record of rewarding treacly, smug, politically convenient cringe cinema.

To be fair, One Battle After Another is a far better movie than Crash or Green Book. The latest from Paul Thomas Anderson is a loose—very loose—adaptation of Thomas Pynchon's Vineland, with the book's Ronald Reagan-era setting updated to the present. And Anderson is one of the most accomplished directors of the last three decades: There Will Be Blood is one of the two or three best movies of the 2000s, and he's directed a handful of other modern classics. Even his worst movies have quite a bit to recommend.

But One Battle After Another, despite some standout moments, is not one of his best. The reason is that it caters precisely to the sort of self-satisfied, self-flattering liberalism that Hollywood likes to reward.

I say this as someone who is at least partially sympathetic to one of the film's big political hobbyhorses: immigration.

At the heart of the film's shaggy, sprawling narrative—this is, after all, based on a Pynchon novel—is a leftist militant group known as the French 75. When we first meet them, they are liberating a group of immigrants from an American detention center. This is not a peaceful, democratic action: Their plot involves guns, explosives, and tying up guards. Anderson is smart enough to let viewers see that the revolutionaries are in it for more than just the cause: They get off on the violence, quite literally, with the group's leader, Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), using the action to both rally the affections of her boyfriend, an explosives expert who becomes known as Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio), and force the center's commander, Col. Steven Lockjaw (Sean Penn), into debased sexual submission. Lockjaw digs it too, tracking her down for an illicit fling that will change both their lives.

Over the course of the film's first act, Hills has a baby daughter, and the French 75's violent antics escalate. They bomb the offices of anti-abortion congressmen and others. And eventually they stage a bank robbery that goes deadly wrong when Hills shoots and kills a security guard. The group scatters, Hills is caught, and in exchange for avoiding jail, she gives up the whereabouts of her leftist comrades.

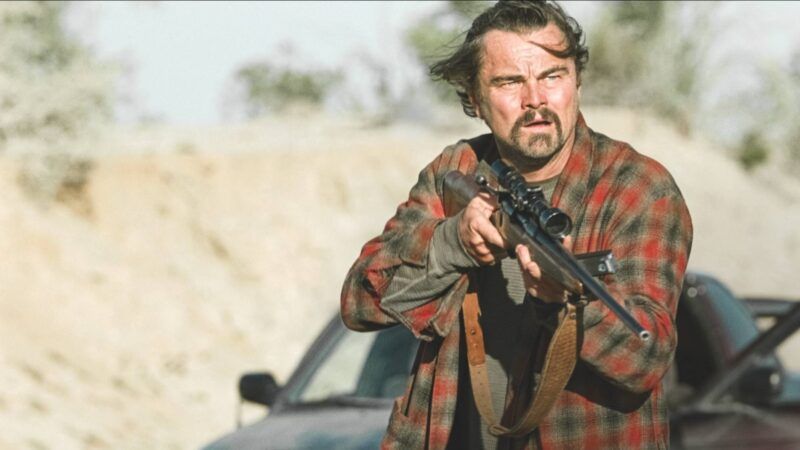

The story picks up a decade and a half later, with DiCaprio's former bomber living in hiding with Hills' daughter Willa, now a teenager. He's become a joke of a liberal radical—a scatterbrained pothead who can't remember which pronouns to use with his daughter's friends. But soon, Lockjaw picks up their trail, and the movie turns into an extended chase, as Bob and Willa make their way out of a California town that's been turned into a sort of Underground Railroad for immigrants while it's under assault from Lockjaw and the forces he controls.

You can see what Anderson is going for: He wants to cast today's aging liberal establishment as incompetent and ridiculous, drug-addled and tediously obsessed with useless language policing—while at the same time depicting the real horrors of a kind of fascist, crypto-racist state. Lockjaw's military subordinates are shown to be terrifying and cold-blooded in their methods, and Lockjaw himself has been inducted into—I promise I am not making this up—a secret Ku Klux Klan–like white supremacist group that is Christmas-themed, in which members salute each other with "Hail, Saint Nick."

Sometimes the movie is indeed quite funny. And there are multiple tense, complex action setpieces that keep the film charging forward. At a little more than two hours and forty minutes, it's somewhat overlong, but it's never boring.

The problem is that Anderson can't really bring himself to reckon with the darkness and violence of his radical left heroes. The film's first 40 minutes show the French 75 bombing buildings, robbing banks, and leaving a body count in their wake. But the film prefers to critique them as absurd and ineffectual rather than as the violent radicals they are. (Later, when the film cuts to the present day, it diminishes the possibility of activist violence, casting incendiary acts as false flag operations by Lockjaw's forces.) The film's most provocative idea, that Hills is selfish and drawn to radicalism for its kinky thrills, is left underexplored.

Fundamentally, the movie casts its radicals and revolutionaries as endearing and even deeply righteous in the face of a racist, fascist government. And, while it mocks today's aging left, its mawkish coda thrills to the idea that the next generation might take up their cause.

Like I said, I'm at least partially sympathetic to the film's ideas, especially its worries about militarized immigration crackdowns. And there is a kind of temerity in depicting a leftist alliance against incipient fascism as populated by mockable doofuses. But One Battle After Another lets its violent leftists off the hook a little too easily. Whether or not Hollywood's tastemakers reward it for its softness and self-flattery, what's clear is that everyone involved is a little too sympathetic to the cause.

Show Comments (77)