Advocates of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy Complain that 'the FDA Moved the Goalposts'

The agency's puzzling concerns about the Lykos Therapeutics drug application

When the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) declined to approve MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) last year, the details of its objections were not publicly known. Last week, more than a year after that decision, the FDA clarified its reasoning by publishing the full text of its "complete response letter" to Lykos Therapeutics, the company that submitted the drug application.

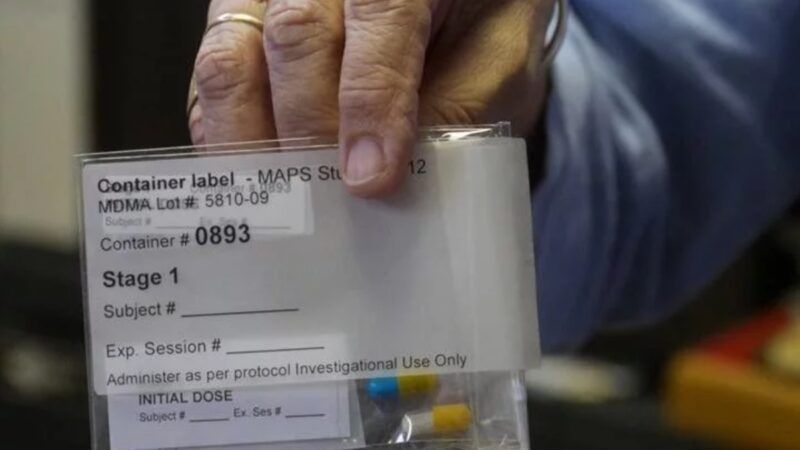

The research that the FDA considered was spearheaded by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), which created Lykos to market MDMA as an FDA-approved medication. On their face, the results from the two Phase 3 clinical trials were impressive.

The first study, published by Nature Medicine in 2021, involved 90 subjects with "severe PTSD," as measured by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). That questionnaire is designed to assess problems such as "intrusive distressing memories," hypervigilance, an exaggerated startle response, sleeplessness, difficulty in concentrating, avoidance of cues associated with a traumatic event, and "feelings of detachment or estrangement from others." The second study, reported in the same journal two years later, involved 104 subjects with "moderate to severe PTSD."

Both studies found that subjects who received MDMA saw larger reductions in their CAPS-5 scores than the control group, which underwent the same sort of psychotherapy but received a placebo. The differences were substantial. On average, CAPS-5 scores, which range from 0 to 80, fell by more than 24 points in the MDMA group in the 2021 study, compared to about 14 points in the placebo group. At the end of the study, two-thirds of the MDMA group "no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD," compared to one-third of the control group. In the 2023 study, the average score decreases were about 24 points and about 15 points, respectively. More than 70 percent of the MDMA group no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis, compared to 48 percent of the control group.

The FDA's letter raises three main issues. The FDA deemed information about "adverse events" inadequate because it did not include "positive" or "favorable" experiences that might have illustrated MDMA's "abuse potential." The agency also said Lykos had not provided enough evidence of the treatment's long-term effectiveness, and it expressed concern about the relatively high rate of prior MDMA experience among subjects, which it worried could have biased the results.

The objection regarding adverse event reporting is a bit puzzling. The guidance and training manual for the Phase 3 trials defined an adverse event as "any undesirable, unfavorable, inappropriate, or untoward medical occurrence in a patient while participating in a clinical trial." The guidance emphasized that such events do not include "positive or favorable effects."

Although that definition seems logical, the FDA says the researchers should have reported "adverse events associated with abuse potential," such as "euphoria-related experiences" or "mood changes," "even if they are considered desirable." In other words, even if neither the subjects nor the researchers viewed an effect as negative, it still should have been reported as an adverse event.

The FDA also said Lykos had not "demonstrated that the effect observed with [MDMA] is durable beyond the 18-week end-of-study assessments," which happened eight weeks after the subjects completed the last of three sessions. "As PTSD is a chronic condition, any drug indicated for the treatment of PTSD is expected to provide a durable treatment effect," the FDA's letter says. "Given the proposed dosing regimen of [MDMA] of a limited duration of three treatment sessions, it is critical to understand whether the treatment benefit is durable beyond the Week 18 assessment to inform the appropriate use of [MDMA] for labeling of the drug."

Although Lykos did submit data from longer-term follow-ups, the FDA said those assessments may have been subject to "self-selection bias" because "only a portion of participants" were included. In other words, the long-term effect may have been exaggerated if subjects with the most positive experiences were especially likely to participate. The letter also notes that the longer-term assessments "consisted of only a single visit" and that the timing of those visits covered "a wide range" of six months to two years.

Finally, the FDA noted that about 40 percent of the trial participants reported prior MDMA use. That rate, it said, seems high compared to survey results indicating that "individuals with past-year moderate or severe mental illness" were about half as likely to report MDMA use. That contrast, the letter says, raises the possibility of selection bias, casting doubt on the generalizability of the findings. It also "raises the possibility of expectation bias," the FDA says, "given that participants who have prior experience with [MDMA] are more likely to recognize the effects" of the drug.

That last point relates to the double-blind design of the studies, which meant that neither the subjects nor the researchers assessing them were supposed to know who had received MDMA and who had received the placebo. Such ignorance is very difficult to maintain in any study involving psychedelics, since subjects are apt to figure out whether they received the real thing based on the psychoactive effects they experience. That challenge, the FDA suggested, was compounded by the fact that two-fifths of the subjects had used MDMA before.

One way of addressing that problem, the letter says, would be to include "a low-dose [MDMA] arm as a control." Under that approach, subjects who received low doses might experience some of MDMA's effects, leading them to expect positive results. In theory, any difference in results between the low-dose and full-dose groups could be more confidently attributed to MDMA, as opposed to expectations primed by "functional unblinding."

During a press briefing on Friday, Rick Doblin, the founder and president of MAPS, complained that the issues highlighted in the agency's letter amounted to a "changing of the goalposts," since the FDA had not raised those concerns during extensive discussions about "every single aspect of the protocol design." For example, he said, the FDA had recommended against including a low-dose comparison group, the very solution it later suggested. And despite the agency's concern that prior MDMA experience may have biased the results, he said, there was no significant difference in outcomes between subjects who had previously used MDMA and subjects who had not.

"The FDA moved the goalposts," MAPS said in a statement. "After the trials were complete and the application accepted, FDA shifted its standards regarding the approach to the challenge of conducting double-blind studies. In addition, FDA demanded more information after patients and researchers had already poured years of their lives into this process."

Lykos is not giving up, MAPS emphasized. "Lykos will continue negotiations with the FDA," it said. "MAPS will keep driving forward: incubating and accelerating new MDMA-focused research, training therapists around the globe, catalyzing humanitarian projects in high trauma/low resource areas of the world, and building the infrastructure for a future where psychedelic-assisted healing and personal growth is not delayed by shifting politics, but delivered as a matter of compassion and justice."

Show Comments (12)