No, These New Studies Don't Show an AI Jobs Apocalypse Is Coming

Economists at the Federal Reserve and Stanford University recently published studies investigating how AI affects employment in different industries.

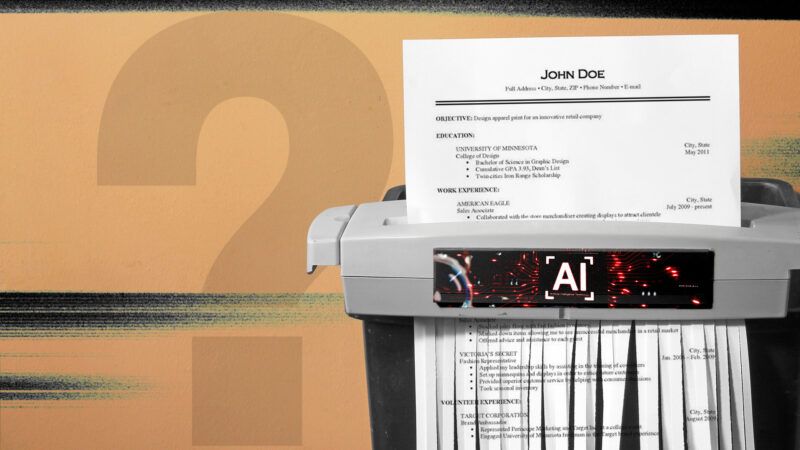

The artificial intelligence (AI) age is upon us and, as is the case with every disruptive technology, it is accompanied by doomsayers who fear it will irreparably harm society. "For Some Recent Graduates, the A.I. Job Apocalypse May Already Be Here," The New York Times recently warned in a recent headline. "There Is Now Clearer Evidence AI Is Wrecking Young Americans' Job Prospects," read another headline in The Wall Street Journal. While these pessimistic headlines evoke a Philip K. Dick sci-fi dystopia, emerging data paint a brighter, more nuanced picture.

The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published a report on Tuesday that explores how AI adoption is associated with unemployment, which is up to 4.2 percent according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' dismal July jobs report.

The authors use two metrics to offer a tentative, noncausal answer: theoretical AI exposure, which measures whether large language models (LLMs) "can reduce task completion time by at least 50%" in various occupations; and actual AI adoption, based on responses to the Real-Time Population Survey created by Adam Blandin, professor of economics at Vanderbilt University, and Alexander Bick, an economic policy advisor at the St. Louis Federal Reserve. According to the study, computational and mathematical occupations had the most exposure (roughly 80 percent), the highest rate of AI adoption (45 percent), and the largest increase in their unemployment rate between 2022 and 2025 (by 1.2 percentage points). Personal services, meanwhile, had the least exposure (about 15 percent), the lowest rate of AI adoption (less than 10 percent), and the smallest increase in its unemployment rate between 2022 and 2025 (by less than 0.1 percentage points).

This elevated unemployment rate in high-AI adoption occupations should be taken with a grain of salt. Will Rinehart, senior technology fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, tells Reason that both measurements used by the Fed have their own problems. Rinehart explains the actual AI adoption measure is suspect because, "in social media research, self-reports of Internet use 'are only moderately correlated with log file data.'" To know the actual "actual AI adoption" rate, "we need log file usage data [from] Anthropic and OpenAI," says Rinehart.

Conveniently, the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI also published a working paper on Tuesday that uses Anthropic's generative AI usage data. The researchers found that, "among software developers aged 22 to 25…the head count was nearly 20% lower this July versus its late 2022 peak," reports the Journal. The researchers also find that, "for the highest two exposure quintiles employment for 22-25 year olds declined by 6% between late 2022 and July 2025." These findings lend credence to the viral New York Times article recounting the nightmarish job application struggles of four recent computer science graduates.

But 2022 was a unique year, and using it as a baseline could be skewing the data. As Matthew Mittelsteadt, a technology policy research fellow at the Cato Institute, tells Reason, "Everyone was online during the pandemic [and] tech had record profits." Mittelstead says the sector may be in the midst of a post-pandemic readjustment that is happening at the same time as AI adoption. The Journal acknowledges these factors could partially account for the reduced employment of 22-year-old to 25-year-old software developers, but argues these "possibilities can't explain away the AI effect on other types of jobs," such as customer service representatives.

AI adoption is undoubtedly causally responsible for some workers losing their jobs. Every productive technology replaces the labor of some workers—but it usually does so by complementing the labor of others. The Stanford researchers found precisely this: "While we find employment declines for young workers in occupations where AI primarily automates work, we find employment growth in occupations in which AI use is most augmentative."

Both of these studies only explore one side of the equation: employment. But AI's effect on productivity must also be considered to understand its actual economic impact. Rinehart says AI's productivity effects are real and measurable and cites four papers published between 2023 and 2025 to substantiate the claim that "productivity gains are typically largest for lower-skilled workers and smaller for highly experienced workers." On the other hand, Mittelsteadt points to a Massachusetts Institute of Technology "study that found '95% of organizations found zero return despite enterprise investment of $30 billion to $40 billion into GenAI.'"

AI is an instance of creative destruction, just as the automobile was for the horse-drawn carriage. Only time will tell if AI is more creative than destructive. But if it's like the technologies that preceded it, there's reason to believe that its permanent expansion of the total economic pie will more than offset the unfortunate unemployment effects borne by particular workers in the short run.

Show Comments (25)