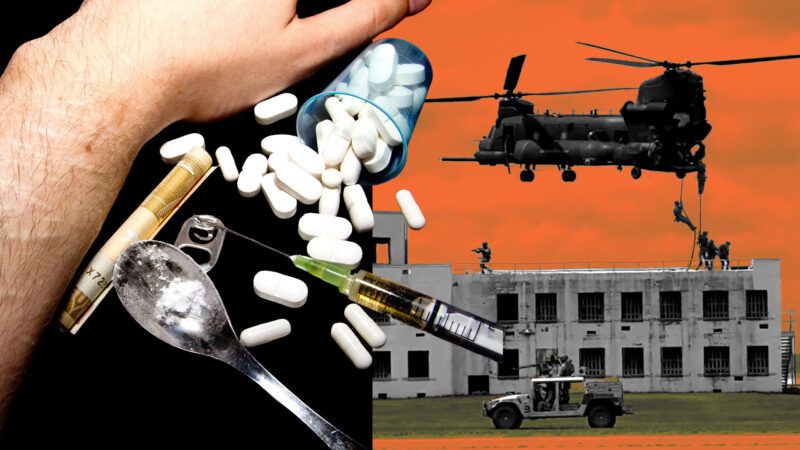

How Elite Special Operations Troops Created a Drug Cartel

A bizarre criminal conspiracy in the ranks of the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg

The Fort Bragg Cartel: Drug Trafficking and Murder in the Special Forces, by Seth Harp, Penguin Random House, 368 pages, $30

Despite the drug war, U.S. intelligence agencies have sometimes made common cause with rebel forces or client states that dealt in narcotics. Alfred McCoy's bombshell 1972 book, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia, exposed opium-fueled proxy warfare in Vietnam and Laos, embarrassing the CIA. The Kerry Committee report in 1989 did the same for cocaine-funded operations in Nicaragua. Similar reports popped up throughout the long U.S. engagement in Afghanistan.

The Fort Bragg Cartel, by the longtime Rolling Stone journalist Seth Harp, is about something different: U.S. troops themselves running a smuggling ring inside America. Throughout the early 2020s, there was a wave of disturbing crimes related to the shadowy Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Harp demonstrates that government officials turned a blind eye as JSOC operators stole, killed, raped, and smuggled, shielding them from both military and civilian justice.

At first, it may be hard to understand where the word cartel in Fort Bragg Cartel comes from. The first half of the book is a history of JSOC—an organization that includes Delta Force and SEAL Team Six—and a collection of seemingly unconnected stories about JSOC veterans behaving badly. But the conspiracy comes into focus in part four. Former U.S. Army quartermaster Timothy Dumas and former policeman Freddie Wayne Huff were leading a criminal enterprise that brought together JSOC operators, the local redneck mafia, Puerto Rican smugglers, Los Zetas of Mexico, and even a former Islamic State fighter.

Huff spoke freely to Harp about his crimes and their military connections from his cell in a federal penitentiary. He was the lucky one. Dumas, who had threatened to expose a giant criminal operation within JSOC, was murdered in the woods outside Fort Bragg alongside active-duty Delta Force soldier Sgt. William Lavigne in December 2020. Although police have charged a local career criminal for their deaths, every local that Harp spoke to was skeptical that the government had the right man. Many of them implied that there was a larger conspiracy.

From late 2020 through early 2023, 12 Fort Bragg soldiers were murdered or accused of murder, and some of these cases remain unsolved. Violent crime in the area is so bad that the nearby town of Fayetteville is nicknamed "Fatalville." The most infamous case might be the murder of Spc. Enrique Roman-Martinez. Suspected of selling LSD, he disappeared in May 2020 during a camping trip. A few days later, Roman-Martinez's decapitated head washed up on a beach. The case is still completely cold.

In a 2021 interview with military police, obtained by Harp, the commander of Delta Force's administrative headquarters complained that JSOC was sending problem soldiers and accused criminals to serve desk duty in his unit rather than discharging them from the military. "Having some of the most tactically skilled, physically fit, and intelligent operators in the military coming in on bad terms is dangerous," the commander said. "We intentionally limit their physical presence as it is a hindrance to the good order and discipline of the company."

By Harp's account, the lack of discipline was an inherent part of JSOC's mission. The force was founded in the late 1970s, when Congress was intensely scrutinizing the CIA, and it became a way for the White House to conduct intelligence gathering and covert operations without as much oversight. During the war on terror, its operators spent long tours of duty killing at an extremely fast pace, without the same oversight as other units. Troops attached to JSOC had access to plenty of unsupervised resources, including bundles of hard cash (for paying informants) and military-issued drugs such as dextroamphetamine, commonly known as Adderall.

Note that JSOC was in the spying business as well as the killing business. JSOC refined the Find, Fix, Finish, Exploit, Analyze, and Disseminate (F3EAD) cycle. The force would seize as many documents and hard drives as it could after an F3EAD assassination, reconstructing the target's network of contacts, then assassinate those people too. The 1984-style surveillance that JSOC set up in the Middle East left a distinct impression on the people in charge of running it.

"There is no data that is not accessible to them," Jordan Terrell, a former IT contractor for Delta Force, warned Harp. "Anything you can think of in a sci-fi movie, it all exists in the real world."

Some JSOC operators seem to have brought an extremely cynical and paranoid approach back home. Their "training was such that if you can't control it, you kill it," to quote Penny Flitcraft, whose daughter was murdered by Flitcraft's Delta Force son-in-law in 2002.

Lavigne himself shot dead a fellow soldier, Sgt. 1st Class Mark Leshikar, in March 2018, after Leshikar accused Lavigne of being a spy during a drug-fueled bender at Disney World. Civilian police handed Leshikar's case to military police, who declined to prosecute the shooting despite some significant holes in Lavigne's self-defense claims. At Leshikar's memorial service, a drunk JSOC reservist cornered Terrell in the bathroom and accused him of wearing a wire, Terrell told Harp.

Fourteen deployments had left their mark on Lavigne. He came back with a serious addiction to stimulants, confiding in a friend that he had killed a child in combat and "we shouldn't be doing what we're doing over there." (Leshikar would similarly tell his wife, "You know I'm a bad person, right? I kill people for a living.") After Leshikar's death, Lavigne sank further into a cycle of guilt and bad behavior, dabbling with the criminal underworld while medicating himself with hard drugs.

Huff had a parallel disillusionment from the civilian police. As a North Carolina state trooper, he became skilled at finding and seizing large amounts of "suspicious" cash from drivers' cars under civil asset forfeiture. Later, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration deputized him to its intelligence office. In Huff's telling, he was fired from law enforcement after writing a DUI ticket for a politically connected driver.

Using his knowledge and connections, he built a Breaking Bad–style drug empire. Huff moved kilograms of cocaine through his suburban house, all while presenting himself as a well-dressed small businessman who dealt in used home appliances. The wild story of Huff's rise and fall by itself makes the book worth reading.

"They were buying dope from the cartel," local pawnbroker Sharon Shivley told Harp. "Somebody that's associated with Mexicans. Who will kill you if you don't pay for your shit." As it turns out, Huff's supplier was Los Zetas, a gang founded by a renegade Mexican special forces unit—trained, ironically, at Fort Bragg.

Dumas had a more mundane, yet possibly more revealing backstory. As a logistics officer in a support unit for JSOC, he was discharged after his smuggling of stolen government property became too big to ignore. Dumas got involved in the cartel after one of Huff's warehouse employees, who had allegedly joined the Islamic State group in Syria and then defected back to America, introduced the two.

Lavigne and Huff escaped so many close brushes with the law that other gangsters wondered whether they might be police informants. But the Fort Bragg cartel appears to have been protected instead by North Carolina's good old boys' culture. Veterans can "show up in their Class A uniforms looking great" to court and expect to have any charges thrown out with a "thank you for your service," said Det. Diane Ballard, a former tenant of Dumas'. Although Huff was a civilian, he had his own network of law enforcement friends to lean on. According to Harp, court documents also imply that Huff had gay sexual blackmail material on at least one law enforcement officer.

The murder of Dumas and Lavigne finally forced the government's hand, bringing the full force of the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security down on Huff's network. Still, Harp suggests that the authorities haven't really followed up on every possible lead.

A few months before he was killed, Dumas gave Huff a USB drive with a letter naming soldiers involved in a wider network trafficking opiates from Afghanistan. Huff, who read the letter, called it an "insurance policy" and "seriously incriminating shit." Three other people independently mentioned the letter to Harp on the record. After Huff was arrested, the USB drive was seized by the Winston-Salem Police Department—which told Harp that the drive was completely empty.

It's common now, almost to the point of cliche, to speak of "the war coming home." And to a large degree, the Fort Bragg cartel was a case of war-on-terror blowback. But exposure to combat doesn't automatically turn soldiers into criminals. Nor do hard drugs. What all the characters involved in this bizarre saga had in common was a total lack of accountability. As long as America treats JSOC as a warrior caste above the law, some of these warriors will abuse their privileges.

Show Comments (5)