Did USAID Really Save 90 Million Lives? Not Unless It Raised the Dead

A Lancet study’s inflated numbers are being used to push a partisan narrative, not inform public policy.

"Is [the U.S. Agency for International Development] a good use of resources?" James Macinko, a health policy researcher at UCLA, asked in an NPR interview this month. "We found that the average taxpayer has contributed about 18 cents per day to USAID." That "small amount," Macinko estimated, had prevented "up to 90 million deaths around the world."

Macinko was referring to a study he coauthored, which was published in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet. In addition to estimating that USAID programs had saved 90 million lives from 2001 to 2021, Macinko and his colleagues project that if the Trump administration's USAID cuts continue through 2030, an estimated 14 million people could die who otherwise would have lived.

In the same NPR story, Brooke Nichols, an infectious disease mathematical modeler and health economist at Boston University, gushed about the study. "Putting numbers to the lives that could be lost if funding isn't restored does something very important," she said. "I like [the study's] statistical approach; it was really well done and robust."

To the contrary, the study's statistical approach was poorly done and not at all robust. But you need not be an economist or a mathematician to recognize that its results are absurd. The authors failed to apply common sense to the numbers, and so did reporters at NPR, the BBC, the Associated Press, NBC, and other news outlets that amplified the study's findings.

Is it plausible that USAID programs saved more than 90 million lives from 2001 to 2021? Let's compare that to the total decline in worldwide mortality during the same period.

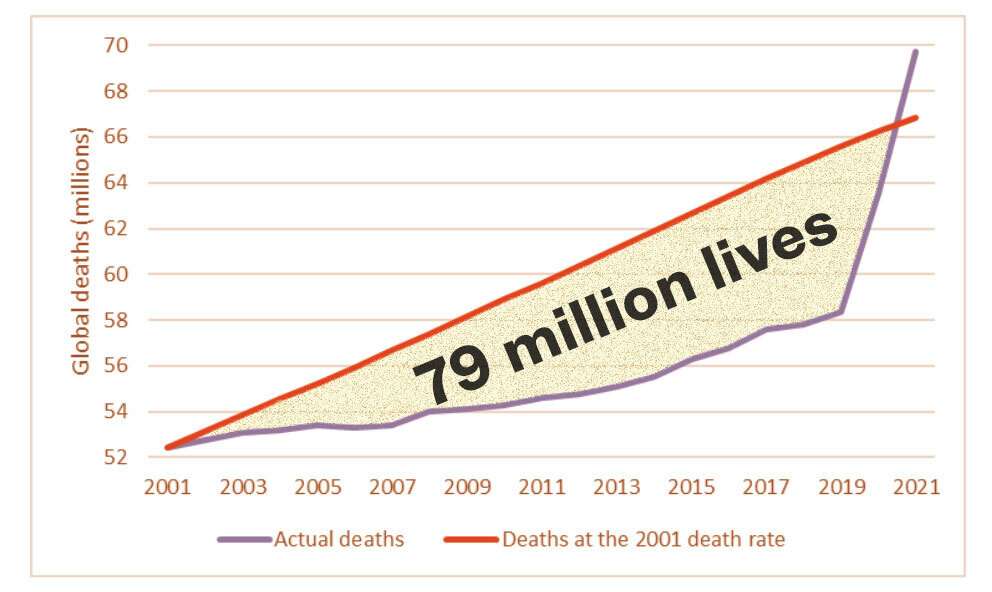

In 2001, the United Nations reports, there were 52.43 million deaths, or 8.4 per 1,000 people. In 2002, the death rate fell slightly; if it hadn't, 370,000 additional people would have died. In 2003, if the 2001 death rate had stayed constant, 750,000 more would have died, and so on. If you add up all the people who would have died over 21 years if the 2001 death rate had remained constant, you get 79 million lives saved.

The Lancet study claims USAID programs saved more than 90 million lives during this period. In other words, USAID was allegedly responsible for the entire global improvement in mortality, plus another 11 million lives.

If you drill down into the numbers, the claim gets even more absurd. Most of the mortality decline (47 million of the 79 million) occurred in China, which received only 73 cents per capita annually from USAID. The least developed countries—the ones with the highest per capita USAID spending—actually saw an increase in mortality of 8 million during the study period, thanks to higher average death rates from 2001 to 2021.

Even if you believe that foreign aid is the primary cause of the declining death rate, these numbers make no sense. USAID comprises about 60 percent of U.S. foreign aid, and the U.S. contributes about a third of all government aid worldwide. Private cross-border charity dwarfs the USAID budget. Was all that money wasted while USAID funds were well-spent? Did advances in medicine, agriculture, public health, and economic growth have no role?

Anyone claiming that USAID was the sole source of declining global mortality during the two decades covered by The Lancet study bears a tremendous burden of proof. Yet the study does not provide convincing evidence of any mortality reduction attributable to USAID.

Studies of this sort often involve problematic data, plagued by missing values, inaccurate numbers, and changes in definitions. Such data require complex processing. To avoid reporting risible results, researchers must do constant reality checks. If simple analysis reveals an effect, more complex methods can refine it, making the result more certain and precise. But when simple methods show no effect, as in this case, it is dangerous to rely entirely on complex methods whose results defy common sense.

The authors of the study began with a common academic approach called "regression analysis." They compared average mortality declines in countries with little or no per capita USAID spending to declines in countries with high per capita USAID spending.

Regression analysis shows only correlation, which does not demonstrate causation. Most researchers are careful to note this distinction. But Macinko et al. claimed their analysis showed USAID caused mortality declines, which is statistically impossible.

That assumption is particularly problematic in this case because a lot of USAID spending went to the same countries that also get aid from other sources. Effectively, the authors gave USAID credit for all the aid that countries received, no matter the source.

In any case, simple regression analysis did not demonstrate any correlation between per capita USAID spending and mortality declines.

For four of the 21 years in their study, Macinko et al. used "dummy variables" to ignore data showing USAID was associated with mortality increases. Their excuses for excluding two of the four years were the 2008 global economic shock and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. So why exclude the remaining two? "To adjust for major economic and health shocks," the authors say, with no clue about what those shocks were and why they were more important than shocks in other years.

It's not clear why shocks should be ignored in the first place. Does it not matter that USAID recipient countries were hit harder by COVID and the global financial crisis than other countries? Does USAID only save lives in calm times and cost lives in turbulent ones? If so, don't we care about the net lives saved or lost at all times?

Next, the researchers tested 48 "control variables." The purpose of these adjustments is to account for factors unrelated to USAID spending that affect mortality rates. Unfortunately, in this case, there are no good controls. For example, the study included education spending and the availability of piped water; however, since USAID funds education and water infrastructure, these factors are related to the amount of USAID received. All the control variables tested were things affected by USAID spending.

Including controls that are causally linked to your main variable of interest—USAID spending in this case—can cause illusory effects to appear statistically significant. This is particularly problematic when you select a large number of control variables relative to the number of data points and choose those control variables from a long list of candidates.

Macinko et al. did not preregister their controls, meaning they did not publish a research plan that committed them to a particular set. That safeguard aims to prevent researchers from falling prey to the temptation of selecting control variables based on whether the results align with their preconceptions.

What about the estimate that the Trump administration's USAID cuts, if continued, will result in 14 million preventable deaths by 2030? Programs like USAID have numerous consequences, both positive and negative, and it is impossible to accurately calculate or project their impact with any confidence. Pretending to have scientific confidence in a quantitatively dubious measure, such as lives saved, is irresponsible and leads to a loss of trust in science.

The Lancet study seems designed to generate a partisan talking point, suggesting that anyone who supports the Trump administration's actions values 18 cents over 90 million lives. Note the trick of making the cost look small by dividing it among 150 million U.S. taxpayers and 365 days per year while making the benefit look large by totaling it over the entire globe for 21 years.

This study has nothing to do with science. It waves the bloody shirt while feigning scientific detachment.

Show Comments (68)