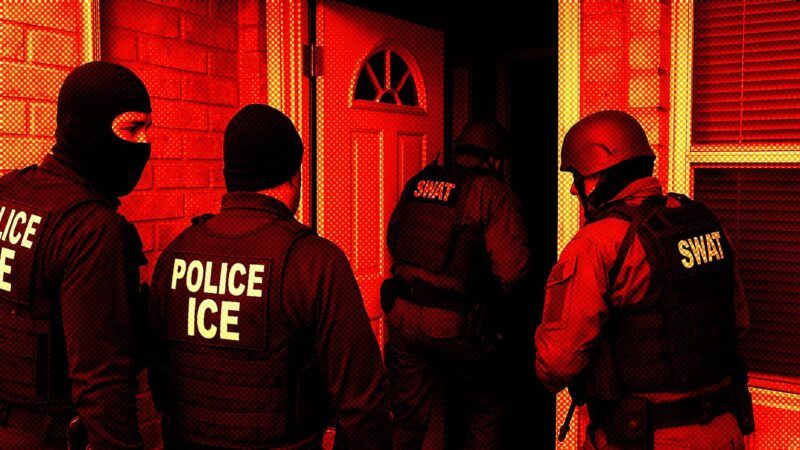

Masked ICE Agents Are a Danger to Both the Public and Themselves

When cops don't look like cops, they run a greater risk their target will fight back.

Masked federal agents have repeatedly grabbed people in immigration raids over the past few weeks. Most seem to be members of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), but in the moment there is often little to indicate who they are. This presents a danger not only to the public but to the masked agents themselves.

"There is no federal policy dictating when officers can or should cover their faces during arrests," CNN's Emma Tucker reported in April, "but historically they have almost always worn them only while performing undercover work to protect the integrity of ongoing investigations." At the time, masked plainclothes agents with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had recently arrested Rumeysa Ozturk, a Tufts University graduate student from Turkey, on little more justification than her having co-written a student newspaper article critical of Israel.

Rather than expressing any unease about anonymous government agents, prominent Republicans have doubled down. Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R–Tenn.) introduced a bill to make "doxxing" federal law enforcement officers a crime punishable by up to five years in prison. House Speaker Mike Johnson (R–La.) endorsed the prospect of letting ICE agents remain anonymous, claiming that otherwise "activists" would "put [agents'] names and faces online."

That explanation strains credulity. Government operatives, operating on the public's dime and at least nominally in the public's interest, are entitled to fewer privacy protections while on the job than the rest of us.

"Law enforcement knows the power of a name, the power of identity, the power of accountability. It insists on all three of those things from the public in almost every interaction," police officer and former CIA operative Patrick Skinner wrote in The Washington Post in 2020, as masked federal agents were deployed against protesters. "Yet during a time where identity and accountability are needed most—at the time of most tension—law enforcement says it will provide neither."

Similarly, as Republicans in Congress mulled jail time for anyone who unmasks anonymous law enforcement officers, President Donald Trump posted on social media that "from now on, MASKS WILL NOT BE ALLOWED to be worn at protests. What do these people have to hide, and why???"

"There are instances—like a raid on a murderous cartel or a mafia stronghold—in which it might seem reasonable for police to hide their identities," Samantha Michaels wrote this week at Mother Jones. "But routine immigration arrests don't appear to meet the public threshold for such behavior."

Allowing law enforcement agents to act with complete anonymity means allowing them to operate without effective oversight.

"When New York City's Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) attempted to investigate the hundreds of complaints of police brutality and misconduct during the 2020 George Floyd protests, it was forced to close a third of the cases because it couldn't identify the officers involved," Reason's C.J. Ciaramella wrote last week. "The CCRB noted that it faced 'unprecedented challenges in investigating these complaints' due to officers covering their names and badge numbers, failing to turn on their body-worn cameras, and failing to file reports."

In 2007, agents of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) raided a home in Detroit and roughed up the two women who lived there, but found no drugs. The women tried to sue for damages, but the agents wore face masks, covered their names and badge numbers, and refused to identify themselves at the scene. The suit was dismissed.

Such cases clearly show why allowing officers—empowered to make arrests and potentially kill—to remain anonymous is injurious to both public safety and individual liberty. But masked agents also pose a danger to themselves.

In April, three plainclothes ICE agents detained two men at a courthouse in Charlottesville, Virginia. The agents resisted identifying themselves to bystanders when asked, and one wore a balaclava to cover his face.

"I am…greatly concerned that arrests carried out in this manner could escalate into a violent confrontation, because the person being arrested or bystanders might resist what appears on its face to be an unlawful assault and abduction," Albemarle County Commonwealth's Attorney Jim Hingeley commented at the time. (In a response, ICE not only accused Hingeley of "prioritiz[ing] politics over public safety," but it declared that "the U.S. Attorney's Office intends to prosecute" two women who attempted to question and identify the agents at the scene.)

It's one thing to be approached by a phalanx of police officers, decked out in identical SWAT gear with badges and their agency's acronym emblazoned across the front. It's something else entirely to be swarmed by a group of masked men in street clothes with guns drawn. One could easily mistake them for a criminal gang and might potentially take deadly defensive action.

A similar principle applies to no-knock raids, in which officers are empowered to break down the door to your home without announcing themselves. In that event, the first indication you have that the police have arrived is when something crashes through your front door. You would have no indication whether the armed intruders are police with a search warrant or violent criminals with dangerous intent—and they may feel justified in defending themselves.

That has happened numerous times, with deadly consequences. In 2014, Marvin Guy awoke at 5:45 a.m. as police broke his bedroom window and smashed his front door with a battering ram to serve a search warrant, without knocking first or identifying themselves. Understandably afraid, Guy shot at the intruders, hitting four officers and killing one. A Texas jury convicted him of murder in November 2023.

In March 2020, police in Louisville, Kentucky raided the home of Breonna Taylor on a no-knock narcotics warrant. Taylor and her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, thought they were being robbed and called 911; Walker shot through the front door, and police returned fire, killing Taylor. Police had obtained the warrant on the grounds that Taylor's ex-boyfriend might be sending shipments of drugs to her apartment, though it later emerged that they knew a month ahead of the raid that the packages actually came from Amazon.

Even if you support the mass arrest of undocumented immigrants, it's indefensible to deploy anonymous, unaccountable government agents to carry out that task. Worse, it carries the serious risk of an armed confrontation between law enforcement and well-meaning individuals.

Show Comments (65)