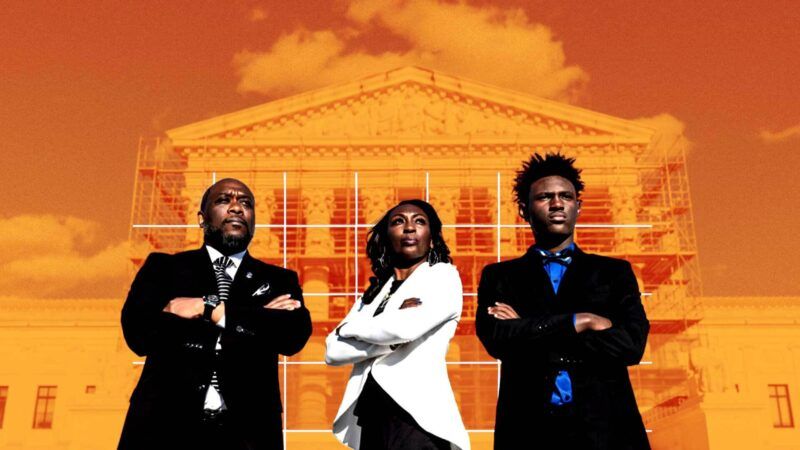

The FBI Raided This Innocent Georgia Family's Home. The Supreme Court Just Revived Their Lawsuit.

Agents detonated a grenade and broke into the house, guns drawn. But while the decision is good news for Curtrina Martin and Toi Cliatt, their legal battle is far from over.

It's been almost eight years since an FBI SWAT team arrived at Curtrina Martin and Toi Cliatt's home, detonated a flash grenade inside, ripped the door off, and stormed into the couple's bedroom with guns drawn. Agents handcuffed Cliatt at gunpoint, and Martin, who had tried to barricade herself inside of her closet, says she fell on a rack amid the mayhem. But law enforcement would not find who they were looking for there, because that suspect, Joseph Riley, lived in a nearby house on a different street.

The issue is still a relevant one for Martin and Cliatt, along with Martin's son, Gabe—who was 7 years old at the time of the raid—as the group has fought for years, unsuccessfully, for the right to sue the government over the break-in.

The Supreme Court on Thursday resurrected that lawsuit, unanimously ruling that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit had settled on a faulty analysis when in April 2024 it barred Martin and Cliatt from suing.

But the plaintiffs' legal battle is still far from over. "If federal officers raid the wrong house, causing property damage and assaulting innocent occupants, may the homeowners sue the government for damages?" wrote Justice Neil Gorsuch. "The answer is not as obvious as it might be."

The issue before the Court did not pertain to immunity for any individual law enforcement agent, whom the 11th Circuit shielded from liability in its decision last year. The justices instead considered if the lower court had erred when it also blocked the suit from proceeding under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA), the law that allows individuals to bring certain state-law tort claims against the federal government for damages caused by federal workers acting within the scope of their employment.

There are many exceptions to the FTCA, however, that allow the feds to evade such claims—a microcosm of the convoluted maze plaintiffs must navigate to sue the government. One of those, the intentional tort exception, dooms suits that allege intentional wrongdoing, including assault, battery, false imprisonment, and false arrest, among several others. Yet the FTCA also contains a law enforcement proviso—essentially an exception to the exception—that permits such claims to proceed when the misconduct is committed by "investigative or law enforcement officers." Notably here, Congress passed that addition in the 1970s in response to two highly publicized wrong-house raids.

The 11th Circuit accordingly observed that the proviso would allow Martin and Cliatt's intentional tort claims to survive the exception. The court killed those claims anyway. It cited the Supremacy Clause, which the judges said protected the government from liability here because its employees' actions had "some nexus with furthering federal policy and [could] reasonably be characterized as complying with the full range of federal law."

Not so, said the Supreme Court. Somewhat surprisingly, that put it in agreement with the government—which, prior to oral arguments, conceded the 11th Circuit's conclusion there was wrong, and that it did not care to defend it. "We find the government's concession commendable and correct," writes Gorsuch. "The FTCA does not permit the Eleventh Circuit's Supremacy Clause defense."

Arguably the bigger question before the Court pertained to a different FTCA carve-out: the discretionary function exception, which, true to its name, precludes claims from proceeding if the alleged misconduct came from a duty that involves discretion. The 11th Circuit dismissed Martin and Cliatt's claims alleging negligent wrongdoing—legally distinct from intentional torts—writing that "the FBI did not have stringent policies or procedures in place that dictate how agents are to prepare for warrant executions." Lawrence Guerra, a former FBI special agent and the leader of the raid, thus had discretion, the judges said.

But the 11th Circuit took its discretionary analysis a step further, ruling that, for acts of wrongdoing that have intentionality, the law enforcement proviso trumps the discretionary exception outright. The justices rejected that. "The law enforcement proviso…overrides only the intentional-tort exception in that subsection," the Court said, "not the discretionary-function exception or other exceptions."

So where does that leave Martin and Cliatt? "On remand, the 11th Circuit will need to decide whether raiding the wrong house is a 'discretionary function,'" says Patrick Jaicomo, an attorney at the Institute for Justice, who represented the pair. Jaicomo was hoping the Court would address that very confusion.

The plaintiffs "call on us to determine whether and under what circumstances the discretionary-function exception bars suits for wrong-house raids and similar misconduct," writes Gorsuch. "Unless we take up that further question, they worry, the Eleventh Circuit on remand may take too broad a view of the exception and dismiss their claims again. After all, the plaintiffs observe, in the past that court has suggested that the discretionary-function exception bars any claim 'unless a source of federal law "specifically prescribes" a course of conduct' and thus deprives an official of all discretion."

The Supreme Court ultimately opted for a narrow approach, though the justices acknowledged "that important questions surround whether and under what circumstances that exception may ever foreclose a suit like this one."

In a concurring opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, said there are no such circumstances when considering the fact pattern presented in Martin and Cliatt's suit. "Like driving, executing a warrant always involves some measure of discretion," she wrote. "Yet it is hard to see how Guerra's conduct in this case, including his allegedly negligent choice to use his personal GPS and his failure to check the street sign or house number on the mailbox before breaking down Martin's door and terrorizing the home's occupants, involved the kind of policy judgments that the discretionary-function exception was designed to protect."

That would seem like the right conclusion, particularly when considering the genesis of that law enforcement proviso, which Congress enacted to give recourse to victims who suffered at the hands of near-identical misconduct. Those lawmakers clearly did not think the discretionary exception would doom their claims. That the law was meant to protect people like Martin, Cliatt, and Martin's son is why a bipartisan group of lawmakers—including Sens. Rand Paul (R–Ky.), Ron Wyden (D–Ore.), and Cynthia Lummis (R–Wyo.), along with Reps. Thomas Massie (R–Ky.), Nikema Williams (D–Ga.), and Harriet Hageman (R–Wyo.)—had urged the Court to take up their case.

Sotomayor's description of Guerra's negligence is also salient and was the subject of one of the more interesting exchanges when the Supreme Court heard the case. Arguing for the Justice Department, Frederick Liu, assistant to the solicitor general, said it was too much for Martin and Cliatt to expect "that the officer should have checked the house number on the mailbox."

"Yeah, you might look at the address of the house before you knock down the door," Gorsuch responded. Liu countered that such a decision "is filled with policy tradeoffs."

"Really?" Gorsuch replied.

Show Comments (9)