How Britain's Protectionist Trade Policies Created Valley Forge

The site of George Washington's famed winter encampment might not have existed without colonial-era iron regulations.

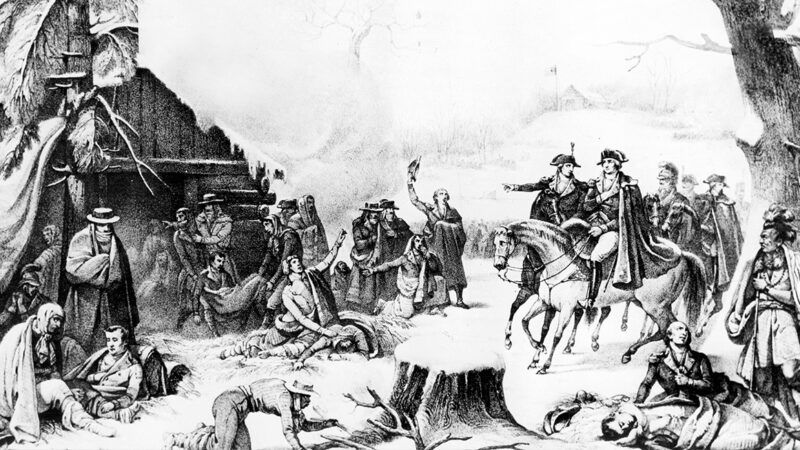

When students of the Revolutionary War hear the words Valley Forge, they probably think of an iconic image: Gen. George Washington kneeling in the snow, surrounded by log cabins, praying for aid.

The Continental Army endured the winter of 1777–78 at Valley Forge, while the British hibernated in nearby Philadelphia. It was that winter, so the semimythologized story goes, that the Americans were sharpened from a ragtag militia that had done little more than strategically retreat during the war's first two years into a force capable of challenging the redcoats.

But before Valley Forge became the "Valley Forge" of American military history, it had already played a smaller, unofficial role in the fight for independence.

This "forge" in its name was a small ironmaking operation established on the banks of the Valley Creek in 1742 as the Mount Joy Forge. It was just one of dozens of small ironworks that popped up across the hills of eastern Pennsylvania in the decades before the revolution. The densely wooded region provided ample fuel for furnaces that smelted iron ore into pig iron and other forms of workable metal, which could subsequently be forged into tools and household goods. The supply chains ran down the river to Philadelphia and from there to the rest of the colonies and the world.

In 1750, however, the British government tried to intervene in that burgeoning market. With the passage of the Iron Act, the American colonies were allowed to produce only unfinished iron and were allowed to export it only to Britain. Finished products would have to be reimported from Britain—with a high tax applied, naturally.

Existing forges, like the one where the Continental Army would later encamp, were allowed to continue operating but could not expand production without permission from the crown.

The law was not always obeyed, as a small exhibit in the stables at Valley Forge National Historical Park explains. In some cases, it may have been openly flaunted. John Potts, who bought the Mount Joy Forge in 1757, founded another forge in the area in 1752, seemingly in defiance of the Iron Act (though historians at the site are unsure of its exact legality).

In the long run, the Iron Act was an utter failure. The mercantilist law incentivized both American producers and colonial officials to ignore it and helped galvanize support for independence among Pennsylvania's commercial classes.

The British army destroyed the Mount Joy Forge on its way to occupying Philadelphia in the fall of 1777. But neither brute military force nor protectionist trade policy could stamp out the market for Pennsylvania iron—without which there would never have been a Valley Forge to serve as the turning point for Washington's army.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "How Protectionist Trade Policy Created Valley Forge."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

My lord, what a silly stretch. The “valley” part was significant to the encampment, not the “forge” part.

Interesting history, though. Exactly the kind of historical tidbit I'd expect to find in a libertarian individualist rag. A little spare on details, though; what exactly did an iron forge look like in the 1750s? One doubts they had hydraulic presses and huge drop hammers forging away. Heck, I don't even know what a modern forge looks like. I've seen many depictions of soldiers in the Continental Army, no need for yet another. Surely the author could have copied one from the museum or even taken a photograph of the museum.

All they had in common was a smelting hearth. From there it depended what the iron was to be used for.

The important part of Valley Forge is the foreigner - Baron von Steuben - who turned the American army from shit into gold.

Obviously an open borders story about naturalization

It's a nice story, and I'm sure he helped, but I believe his standing army was a distraction. It was the militia who hounded and harassed Burgoyne on his march down from Canada, sniped at his officers and sergeants, and of course Burgoyne himself was an idiot who thought carting a baggage train through the woods was a good idea, while Clinton (?) decided to occupy Philadelphia instead of march north and help Burgoyne.

It was also the militia who hounded and harassed Cornwallis in the South and chased him north, where Washington finally made his second smart move, giving up on assaulting New York to trap Cornwallis at Yorktown.

I believe the Revolution was a foregone conclusion, since Britain had to ship almost all supplies other than water across the ocean, and their bureaucracy and King George and Lord Germaine(?) were so fixated on micromanagement from 3000 miles away. The militia alone would have been enough to defeat the redcoats, and they would have had to withdraw on their own eventually. It might have taken longer, but independence was a foregone conclusion after so much British incompetence.

von Steuben's legacy is what made America powerful. Our enduring military advantage over the centuries has been logistics.

The legacy of Saratoga is that it convinced the French to get involved against the British. Not just to fund us but to make it a world war. Another part of the American Revolution we tend to ignore

Nice. Completely dodges what I said. Perhaps you are talking to yourself.

It should dodge what you said. Steuben's legacy at Valley Forge is not about a standing army. Steuben's legacy is even in the Constitution. It is Congress that has the explicit authority To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia,. The militia is not an individual responsibility (as interpreted by many today). It is not a state/local responsibility (as was the case during the revolution). It is a FEDERAL responsibility - re the organizing, arming, and training. THAT is Valley Forge.

God what a statist interpretation.

The Constitution is statist. Get over it. If you don't like it, I understand that Somalia is taking immigrants. No government in most of the country.

The Constitution is statist.

You need to learn the meaning of that word.

It’s incapable of learning.

The federal government didn't take its responsibility for training the militia seriously until it performed poorly in five consecutive wars. After the final such disaster, in the Spanish American War, Congress passed the Dick Act when Theodore Roosevelt was President, creating the National Guard. National Guard units have fought well in every war since.

The militia was never meant to fight foreign wars, you retarded faggot.

Definitely! We would be flying the Union Jack were it not for France.

And you are 100% right about logistics. Eisenhower's brilliant Torch and Overlord amphibious assaults were unparalleled logistical accomplishments.

Had it not been for the real French Army and the real French Navy, the Battle of Yorktown would not have happened. Your vaunted militia had no idea as to how to invest a siege. There would have been no naval blockade, and in fact a relief fleet was underway to try to bring Cornwallis supplies when he surrendered. Cornwallis would have been relieved and the following year he would have destroyed basically everything in eastern Virginia.

The militia played its role, but it took a professionally trained army to start achieving meaningful and lasting victories. At the end of the day, the colonists didn't precisely win so much as they simply convinced Parliament and the Crown that we were just more trouble than we were worth. With England deeply involved in their traditional pastime of fighting the French, the colonies were mostly just a distracting side show. Since the North American colonies had long been a net drain on the Exchequer, they decided to cut their losses.

He wasn't a Baron. But he had been a Prussian staff officer, which made him a foreigner, which will piss off MAGA. And he was Gay, which will piss off a different part of MAGA. And his work in training the Continental Army that is keeping us from having to sing "God Save the King". The other thing that won us the war were the mandatory smallpox inoculations George Washington ordered, which pisses off a third part of MAGA.

And he was Gay

Like Chase Oliver?

The tune is "God Bless America."

Iron had been forged for a century in America when the famous Valley Forge was built. This manufacturing was indeed a threat to special interests in Britain, and the colonists couldn't vote in British elections anyway. So the government protects its special interests. Nothing new under the sun.

Adam Smith railed about these stupid policies. He used to be a Libertarian icon, and also someone those of us who aren't Libertarian but like free markets, free trade, and capitalism appreciate a lot. Libertarians however have replaced Adam Smith with Donald Trump as their ideological leader, at least judging from the comments here.

For a nominally libertarian site, actual (small l) libertarians are sadly underrepresented in the comments. At least I can derive some small amusement from watching the Shit on Reason crowd tie themselves into knots trying to explain how they're the "real" libertarians while the writers are all Nazi-commie-leftards. I'll admit to occasionally posting on sites I fundamentally disagree with, but I usually at least give reasoned arguments a try first. If I do break down to outright trolling, I get bored and move on, usually in a few days or weeks, tops. These buffoons have been at it for years.

Britain eventually learned its lesson, and by the mid 19th century went free trade -- and damn near conquered the world. Protectionism is a way to make your country irrelevant, which is what Trump wants.

On other words . . . what?

The reason the colonists left was because they couldn't make and sell finished products which is utterly not the case with Trump's tariffs.

It's almost as if for every initiation of deadly force there is unequal yet apposite reprisal force.

Today's Yankees would simply freeze and surrender for lack of weapons...

Boldly defying a law is flouting it, not flaunting.