The Anarchist and the Republican

How John McClaughry and Karl Hess fought to decentralize power—one from inside the system, one ever further from it

The man on the motorcycle was an anarchist, a lawbreaker, a guy the Black Panthers could turn to when their leader needed transportation; his FBI file fretted that he might "participate in violent activities, such as bombings, should the right opportunity present itself." He was in Vermont to speak at a hippie college, but he took a detour to visit someone else in a mountainside cabin about 40 miles away.

It was the middle of the 1970s. The man in that cabin was a longtime Republican who had served in the state Legislature. He used to work for Richard Nixon, and he would soon write radio scripts for Ronald Reagan. He and the anarchist had never met before.

They chatted in the kitchen for hours, enjoying each other's company. After all, they agreed about a lot.

The anarchist was named Karl Hess, and—let's get this out of the way quickly—he was not in fact prone to planning bombings. (The surveillance state's files on him got some other things wrong as well, including his wife's name and the color of his eyes.) The Republican was named John McClaughry, and—let's get this out of the way too—his work for Nixon had not made him a Nixon fan.

Each man's career looked like an inverted version of the other's. In 1964, Hess had been a speechwriter for Barry Goldwater, an Arizona senator with a hard-right reputation who had captured the GOP's presidential nomination. McClaughry had been among the moderates who opposed Goldwater, and he had helped shape a speech for Michigan Gov. George Romney when that liberal-leaning Republican was thinking of entering the race. Since then, Hess had shifted to the "left": turning against the war machine, learning to love civil disobedience, developing a distrust for corporate America. McClaughry had moved to the "right," battling land use planners and devising Republican alternatives to Great Society programs.

Yet each had arrived at a similar distrust of the state and other centralized institutions. Both had been involved with the black power and neighborhood power movements, and both liked it when workers owned and managed their own workplaces. And both loved technologies that transfer power from institutions to individuals. It's just that one worked within the system and the other ever further from it—two paths that offer lessons not just in libertarian and decentralist ideas but in the ways people pursue them.

'To an Untutored Youth, It Was Pretty Persuasive'

Hess' media career began in 1938, when the 15-year-old son of a divorced D.C. switchboard operator decided he'd had enough of classrooms. So he registered at every high school in town and then told each one he was transferring. Having trapped the truancy officers in a bureaucratic strange loop, he went to work for a radio station and a series of local newspapers.

Reading Hess' earliest articles, you can catch a hint here and there of the anarchistic attitudes he'd be known for later. In a 1944 report on a jailbreak, he seemed to take delight in the details of the prisoners' escape, saving his disapproving tone for the marshals "with a tenacious passion for anonymity" who threatened to arrest any journalists who photographed the scene. A year later, he set out to see which businesses he could bribe into ignoring wartime rationing rules—not to expose them (he didn't identify anyone) but to file a fun dispatch.

But he was still figuring out his politics. After youthful flirtations with the far right and far left, Hess settled into a long-term relationship with the GOP, taking a strong interest in the fight against communism. While there's an obvious intersection between anti-communism and libertarianism, his anti-communist impulses sometimes overpowered his libertarian ones. When the Coast Guard barred Communists from working as radio officers on privately owned merchant vessels, Hess sided with the government, arguing in a 1949 piece for Pathfinder that the risk of "mutiny or sabotage" meant the feds should insert themselves into these hiring decisions.

At times Hess' anti-communism pulled him into potentially disreputable territories. He cranked out speeches for Sen. Joe McCarthy, the red-hunting Republican from Wisconsin, and he wrote for Counterattack, a sort of blacklister's newsletter. He helped run arms to non-Marxist rebels fighting Fulgencio Batista's Cuban dictatorship. ("I knew when I was very young that he had this connection to Cuba," recalls his older son, Karl Jr., "because we had a garage full of Browning machine guns.") He tried to convince the mobster Frank Costello to finance a plot to kidnap and interrogate Soviet couriers.

None of which kept Hess from rising through the ranks of respectable Republicanism. He was the primary author of two GOP platforms. He ghostwrote for future presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. He worked at the American Enterprise Institute, where he did research for a host of Republican politicians and a few Democrats too, including future Vice President Hubert Humphrey. He was a well-respected man living a comfortable suburban life—you might even call it normal, if you overlooked those Brownings in the garage.

McClaughry didn't have a standard two-parent upbringing either. Born in Detroit in 1937, he was raised mostly by his grandmothers in two Illinois towns, spending his summers in Pontiac and the rest of the year in Paris.* (His Pontiac guardian was much stricter, prompting him to joke later that he would spend nine months with Jesus and three with Jehovah.) He didn't pay much attention to affairs of state until he got drawn into an attempt to draft Adlai Stevenson as the Democratic presidential nominee in 1960. When the party picked John F. Kennedy instead, McClaughry opted not to join the Young Democrats—even then, with his worldview not fully formed, he "didn't see myself as a Democrat because of too much statism"—but he did somehow end up, at age 23, as chair of East Bay Senior Citizens for Kennedy-Johnson. Evidently the party was short on senior citizen talent.

The young McClaughry was still figuring out his political views—he even had a brief dalliance with the World Federalists—but a 1960 book called Decisions for a Better America drew him into the GOP. A manifesto for moderate Republicans, the volume spoke in broad terms about avoiding government intrusion and in specific terms about the many government activities its authors nonetheless favored. The committee that composed it was chaired by Charles Percy, the president of an Illinois camera company. "In retrospect, maybe it wasn't all that good," McClaughry recalls. "But to an untutored youth, it was pretty persuasive."

Increasingly active in Republican politics, McClaughry joined Vermont Sen. Winston Prouty's staff in 1964. He was briefly involved with New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller's presidential campaign during the '64 primaries, although he didn't like most of Rockefeller's platform, because the main alternative—Goldwater—talked about nuclear weapons in a way that McClaughry thought reckless. When Percy ran for Senate in 1966, McClaughry worked for the campaign and then for the new senator's staff.

But he wasn't some buttoned-down D.C. drone. He amused himself by writing politicians absurdist crank letters under assumed names. He had a hobby of hopping freight trains, a pastime that acquired a Coen brothers quality the day a brakeman joined him in the caboose; McClaughry expected to be kicked off, but the fellow instead insisted they sing old minstrel songs together. He built a cabin in the Vermont woods with no plumbing or electricity, then had a more comfortable home erected on the property; in 1967 he became town moderator of Kirby, and he still chairs his community's annual meetings today. He read an assortment of decentralists, and he spent time thinking about ways to devolve power to civil society. That, he found, was not at the top of the Senate agenda.

'You're Not the Only Libertarian on Earth'

Hess' exit from conventional politics began on Election Day 1964, when President Lyndon Johnson dealt Goldwater one of the most crushing defeats in American political history. Over the course of the year, a host of pundits had denounced Hess' boss as a dangerous extremist. More than 1,000 psychiatrists signed a statement declaring him psychologically unfit. A TV ad suggested he might launch a nuclear war. At the University of Maryland, a band of anonymous students dressed in black pajamas snuck out to alter a campaign billboard in the middle of the night, giving Goldwater a Hitler mustache and replacing his slogan—"In your heart you know he's right"—with "In your head you know he's wrong." Come November, he carried only six states.

With defeat came exile. At the Republican National Committee, Hess later recalled, "Anyone retaining an open loyalty to Goldwater and unwilling virtually to denounce him was on the outside." There was still work: When the Los Angeles Times gave Goldwater a column, for example, he hired Hess to write it for him. But there was less work.

Hess started riding a motorcycle in his spare time. This was not yet a trendy thing to do, and some of the neighbors side-eyed him. After a couple of wrecks, he started working with a welder's torch, at first just to fix his bike but then with the notion that it might be another source of income. He and a biker pal put up a shingle as K-D Welding, and soon Hess was simultaneously a self-employed blue-collar worker and one of Goldwater's favorite ghostwriters. He had a side career as an artist too, welding abstract metal sculptures in his bathtub.

A transformation had begun. Even before '64 Hess had been a fan of the novelist Ayn Rand, famous for her hymns to capitalism and rationalism, but by 1967 he was telling a reporter that he reread Atlas Shrugged "every couple of months." Rather than pushing his politics to the right, this made him reconsider his alliances. In a letter to Goldwater, he distinguished "the status quo, mystically religious, elite types such as Bill Buckley" from folks like the senator, who had a "free-wheeling, very non-stuffy, very radical, if you will, open market society and open-mind philosophy."

As he was drawing distinctions within the right, Hess came into contact with the left. The Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), run by former Kennedy staffers who had grown more radical, reached out to him after the election. The group's founders, Marcus Raskin and Richard Barnet, were intrigued by elements of the Goldwater campaign—the senator's skepticism about executive power, his opposition to conscription, the number of large corporations that had been against him—and asked Hess to conduct a seminar. He gave his talk, and then he kept coming back to the institute, both to speak and to listen. He worked with leftists on one of the central libertarian issues of the day, serving alongside the socialist icon Norman Thomas on the anti-draft Council for a Voluntary Military. He met some of the kids who had vandalized that Goldwater billboard, members of a radical group called Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). He told them he thought the prank was clever.

He was becoming more bohemian too. He got into the radical satire magazine The Realist and the iconoclastic comedian Lenny Bruce. (That's something else Hess and McClaughry had in common: Both wrote fan letters to The Realist.) Soon he was growing his hair, living on a houseboat, dabbling in psychedelics, and not always wearing clothes.

In 1968 the transformation shifted into overdrive. That spring Hess published several essays asking conservatives not to turn up their noses at civil disobedience. In the summer he befriended the anarcho-capitalist economist Murray Rothbard, who had taken to arguing that libertarians weren't really right-wing and should be making common cause with the New Left. When Goldwater, hoping to reenter the Senate, asked his old friend to write for his campaign, Hess agreed on the condition that he wouldn't touch the topic of Vietnam, a war he had growing doubts about. One result: At the University of Arizona, the great right-wing menace of 1964 declared that some of the campus radicals' proposals "are just rewrites of old Republican Party platforms." In fact, Goldwater announced, he had "much in common with the anarchist wing of SDS."

As 1969 dawned, Hess announced his break with the right. Everyone from The New York Times to The National Tattler covered the story—the Tattler gave it the immortal headline "Karl Hess: Goldwater Man Freaks Out!"—and one of the country's most popular magazines, at least among men, commissioned Hess to write a libertarian manifesto. "The Death of Politics" ran in the March Playboy, and it was many people's first exposure to libertarianism. Jim Turney, a future chair of the Libertarian Party, remembers walking across Madison College the day the issue appeared. "People came yelling out at me," he says. "My friends were trying to get my attention, basically telling me: Hey Jim, you're not the only libertarian on Earth as we thought. Because there's this article."

For Ken Western, a former editor and reporter at The Arizona Republic who is writing a Hess biography, the Playboy piece was the moment the man's public image clicked into place. "He became the face of libertarianism," Western says. This was a radical face: "The Death of Politics" condemned the Cold War, denounced drug laws, and declared that its author had "a better chance of surviving—and certainly my values would have a better chance of surviving—with a Watts, Chicago, Detroit, or Washington in flames than with an entire nation snug in a garrison." It also saw hope "in the very exciting undercurrents of black power."

'To Own Those Homes'

McClaughry saw hope in those undercurrents too. He had always opposed Jim Crow, though not always from the same perspective as other activists: When he joined the March on Washington in 1963, he got annoyed at a pro-Castro contingent marching near him and left early, missing Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous speech. But he helped coordinate the Republican Party's civil rights activities on the Hill at a time when phrases like "the Republican Party's civil rights activities on the Hill" were not unusual. When militants started shifting their language from civil rights to black power, McClaughry wasn't put off. Indeed, he started using the phrase himself.

He had a particularly strong admiration for Nathan Wright, the man who chaired 1967's National Conference on Black Power. Wright liked McClaughry too—in his 1968 book Let's Work Together, he quoted heavily from a letter McClaughry had sent to a mutual acquaintance. "What you really want, I think, is the power and the means to build the kind of community your people want and deserve to have, and the sole right to benefit from the profits that result," McClaughry had written. "You not only should want better homes, but also to own those homes. You not only should want decent food in the supermarket, but ownership of that supermarket."

McClaughry found allies in the New Breed Committee, a black group battling Chicago's Democratic machine. Its leader, David Reed, favored local control of schools, opposed new high-rise public housing, thought tenants in the projects should be able to buy their homes, and wanted to replace traditional welfare programs with something like Milton Friedman's negative income tax. In 1966 he decided to challenge the octogenarian incumbent congressman; the Percy campaign convinced Reed to run as a Republican and loaned out McClaughry to help. It would have been a long-shot race even if the Chicago machine didn't cheat, but it cheated anyway, and was obvious about it: On Election Day, the police picked up a Reed staffer and locked him in a cage of old documents at city hall.

McClaughry started drafting decentralized alternatives to Great Society programs. His proposals initially kept a substantial role for federal money, but they gradually moved, as he later wrote, from a "'government pump priming and assistance' model" to a "more libertarian 'get the hell out of the way and let people produce' model." The most interesting of his early efforts was the Community Self-Determination Act of 1968, which he and a New Leftist named Gar Alperovitz composed in collaboration with the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). McClaughry and Alperovitz were intrigued by the community development corporations (CDCs) cropping up around America—local groups that could run businesses and channel the profits into social services. Their bill would have used tax incentives and government-insured loans to establish more CDCs. But just to jump-start them: The aim was for the groups to be self-sustaining, and ultimately to supplant the welfare state.

That same year, McClaughry became an intermediary between Nixon's presidential campaign and potentially friendly black power activists. This was not an easy act of matchmaking. At one meeting, the candidate tried to establish a rapport with CORE's Floyd McKissick by going on about how they had both been at Duke, not realizing that McKissick had been there not as a student but as a cafeteria worker. McClaughry also had a hand in writing a Nixon radio address promoting black capitalism. In its most-quoted moment, the candidate called for "black power, in the best, the constructive sense of that often misapplied term."

Once Nixon was in office, his idea of black power turned out to be more about federal loans and set-asides than removing the barriers that suppressed ghetto entrepreneurship. By then McClaughry had returned to Vermont, where he served two terms in the state House of Representatives and founded a small think tank. But he didn't ignore Washington: His institute did some research for a by-product of Nixon's black capitalism initiative, an ineffectual agency called the Office of Minority Business Enterprise. Its final report for the agency, in 1976, recommended shuttering the Office of Minority Business Enterprise.

'Some Chickenshit Code of Good Behavior'

Hess didn't share McClaughry's history in the civil rights movement. I've seen no strong evidence that he was hostile to African-American rights before his shift of the '60s—the only line that would qualify, a 1956 comment in The American Mercury declaring that the United Nations supported miscegenation, was probably added by the Mercury's far-right editor, who drove Hess away by inserting his obsessions into Hess' articles. But aside from a piece in The Freeman decrying the mistreatment of Native Americans, Hess in his conservative days didn't really talk about racial oppression.

He started paying more attention at the peak of his Randian phase. Not, initially, in a particularly political way: He thought the chief force for ending prejudice should be "the color-blind fairness of 'green power,' the open market." But Hess met and was impressed by CORE's Roy Innis, whose mixture of militant and conservative impulses would eventually steer him into the GOP but who at that point had a radical reputation. He got involved as a welding instructor with a black self-help group called the Phoenix Society. By 1969 he was enchanted by the Black Panthers—partly for their rebellious, gun-toting image, but mostly because they offered locally based social services. He didn't like the Leninist jargon that clogged the party newspaper, but the flesh-and-blood Panthers he knew in D.C. struck him as practical neighborhood activists.

So he helped in various ways: MCing an event, editing pamphlets and speeches, doing odd favors. When Huey Newton, the party's "supreme commander," was heading to D.C. for the second Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention in 1970, the local Panthers came to Hess on Thanksgiving morning telling him Newton needed a car. Hess, who by this time was living in a group house in the Adams Morgan neighborhood, asked one of his housemates—Marie Nahikian—if she had a credit card the Panthers could use. She did, sort of: It actually belonged to her employer, the Institute of Scrap Iron and Steel. They and two Panthers rushed to the only car rental place that was open on Thanksgiving, where the sole vehicle available was a yellow Ford. The Panthers insisted that Huey Newton could not be seen in such a car, Hess and Nahikian argued that they didn't have any choice, and eventually the Panthers drove off with it. After a while they even paid for it, though they held onto it for months, during which time the FBI showed up at the Institute of Scrap Iron and Steel to ask what the hell was going on.

McClaughry, for his part, "never saw much of the Panthers as a useful force." The closest he came to the outlaw side of black power was during the New Breed campaign, when David Reed considered an alliance with the city's biggest black gang, the Blackstone Rangers. In his 2012 book Rule and Ruin, Geoffrey Kabaservice reports that this started when the New Breed crew "approached the gang to try to get them not to harm Reed's workers" but progressed to big dreams of "channel[ing] the gang's energies away from violence and into political activism." One white supporter even volunteered to underwrite a Rangers clubhouse.

McClaughry recognized the local clout that could come with the Rangers' support, but he also recognized the risks of working with what was, after all, a criminal organization. He told an intermediary that he'd be willing to get behind the clubhouse idea if the Rangers would "adopt a code of good behavior—like not stockpiling guns and ammo." The middleman came back with their reply: They'd "be pleased to have the clubhouse," as McClaughry summarizes it, "but no honky was gonna tell them they had to have some chickenshit code of good behavior." That ended that. The Rangers eventually found a different patron: They got money from the federal Office of Economic Opportunity.

'None Dare Call It Capitalism'

The first time Hess met a member of the Weather Underground, an infamous SDS offshoot that carried out a clumsy bombing campaign, the Weatherman told him that they'd been together once before, on the top floor of a San Francisco hotel. Hess replied that this seemed unlikely. Not at all, the Weatherman explained: At the time, he had been a Youth for Goldwater leader.

So there was a lot of radicalization going around. And Hess, riding his motorcycle around D.C. with a red fist on the back of his jacket, was in the thick of it. He announced that he would no longer pay taxes, and the IRS put a 100 percent lien on his earnings. The FBI was surveilling him. The CIA was too. He got arrested at anti-war protests. When "The Death of Politics" appeared, Rothbard wrote to Playboy praising the piece but complaining that it had treated left and right as equally bad when "there is a far closer approach to liberty on the New Left today than on the Right." Now Hess had rushed past Rothbard's position, and Rothbard was complaining that Hess led "an extreme-left tendency within the anarcho-capitalist movement"—if, indeed, he was still an anarcho-capitalist at all.

Hess had condemned corporate elites in Playboy, declaring that big business had "become just the sort of bureaucratic, authoritarian force that rightists reflexively attack when it is governmental." As an alternative, he called for "laissez-faire capitalism, or anarchocapitalism." But now he doubted that capitalism was the right term for what he wanted. Maybe the c-word meant those bureaucratized businesses. (He and his friend Neil Nevins planned a book, never completed, called None Dare Call It Capitalism.) Reflecting on his work as a welder, he started questioning any system that gave one group of people entrenched authority over another. "When you go to work, from having been a mandarin…you discover something that's quite compelling," he told an Albany audience in 1972. "These people are actually, totally, absolutely capable of self-management."

In that spirit, Hess praised antiauthoritarian outbursts like the wildcat coal strikes of 1970 and the Lordstown walkout of 1972, where (as the management consultant Peter Drucker later put it) Ohio autoworkers "felt almost to a man that they could have done a better job designing their own work and the assembly line than the General Motors industrial engineers did." Indeed, Hess would praise pretty much any strike where laborers looked past their wages to demand a say in their working conditions.

You wouldn't expect a Reagan speechwriter to condemn capitalism, and McClaughry didn't. But he did take an interest in worker self-management, and even more in worker ownership. (The topics are related but distinct. Many employee-owned companies have traditional management structures, and companies that are not worker-owned will sometimes experiment with devolving decision making to the rank and file.) In a 1972 study for the Sabre Foundation, McClaughry argued that a free society rests on the widely dispersed ownership of property; his report explored a range of options for moving in that direction, including employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs).

McClaughry kept writing about the subject over the next decade, and Sen. Percy inserted one of his articles—a piece on the successes of a worker-owned railroad—into the Congressional Record. When McClaughry served, for about a year, as a policy adviser at the Reagan White House, he was one of a small cell of ESOP enthusiasts. Among other things, they hatched a plan to help the Solidarity revolt in Communist Poland by "subtly strengthening" the case for market forces, private landownership, and "worker ownership and self-management of industry," a pitch that made its way to a National Security Council meeting but does not seem to have gotten farther.

'What Could Be Done at a Local Level'

As Hess settled into his left-libertarian period, he settled as well into Adams Morgan. The neighborhood was going through a radicalization of its own: The counterculture had moved in, and it started building a new set of local institutions—cooperatives, small businesses, community newspapers, a credit union. There was even a parallel local government, a town meeting–style body organized outside the formal state institutions: the Adams Morgan Organization, which Nahikian co-founded in 1972.

"I don't think Karl had had any relationship with a local neighborhood community base until he lived there," says Nahikian, who besides being Hess' credit-card-wielding housemate was now also his colleague at IPS. (After years of attending seminars at the institute, Hess had been named a visiting fellow.) "He was floating around not being entirely sure of what he was doing or what he wanted to do. And it was during that time of living in the house with us on Mintwood Place that he really began to carve out a lot of his thinking about what could be done at a local level."

Hess admired those town meetings, and he loved the idea of giving such neighborhood groups control of the services and resources being monopolized by distant bureaucrats. But his focus was finding ways to produce more food, energy, and other essentials locally, not in a spirit of autarky but in a spirit of flexibility and self-reliance. The Adams Morgan techies worked on a range of projects: chemical toilets, rooftop gardens, a solar collector made of cat food cans, a small soap factory. Hess was heavily involved with two: a neighborhood garden, and an attempt to raise trout in a warehouse. These were low-budget efforts that depended on hasty improvisation (the garden plots were separated by ties scavenged from an abandoned railroad station) and informal agreements (when some preteens started vandalizing the crops, the gardeners put them in charge of a plot, which they took to protecting with the same zeal they'd brought to destroying it).

The tinkerers' biggest success was probably the soap factory, which thrived profitably for years until the people involved went their separate ways. The biggest flop was the aquaculture: The fish tanks needed electricity, the city kept having brownouts, the backup generator didn't last long, and if no one was there to deal with the situation that meant the fish would die. And there weren't enough reliable volunteers to have someone stationed at the warehouse each time the power failed, especially since Hess was often out of town giving speeches.

Those travels had another effect on the group's work. Hess was a charismatic speaker with a knack for communicating excitement for his ideas, and that meant a young person might unexpectedly turn up on their doorstep. "Some impressionable college kid…would be, 'Yeah, I don't need college. I need to be in the world and doing something,'" says Esther Siegel, a core member of the community technology group. Hess adjusted his rhetoric accordingly.

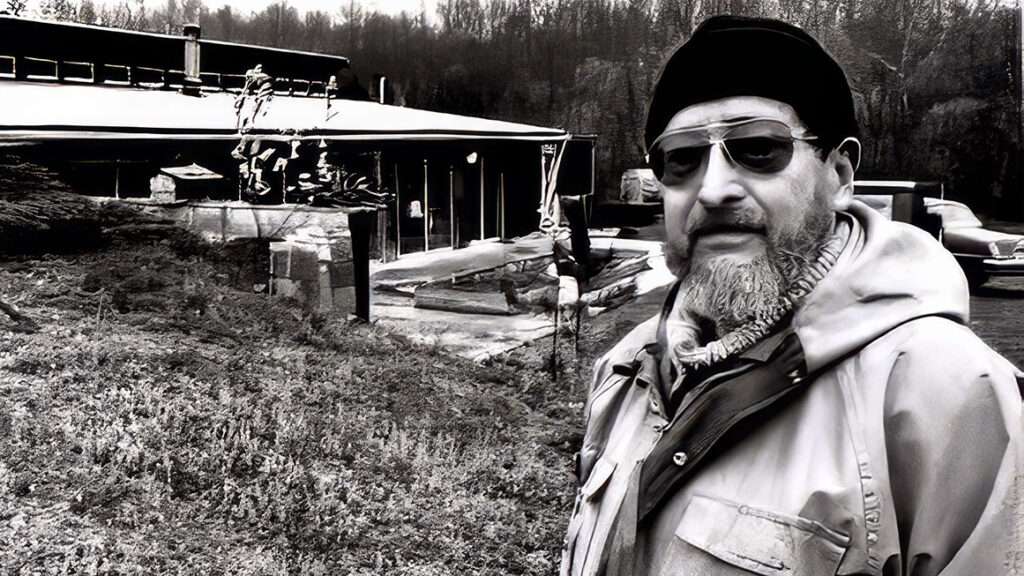

Eventually he adjusted more than his rhetoric. The neighborhood was plagued by crime, and Karl and his wife, Therese, were getting robbed fairly frequently. After a particularly devastating burglary in 1975, they decamped to West Virginia, where they continued their experiments in DIY technology, building an earth-sheltered home largely from secondhand materials, with passive solar heating and a garden.

'To Reverse the Flow of Power'

Word of the Hesses' home reached President Gerald Ford on March 27, 1976, after his plane touched down for a campaign stop in La Crosse, Wisconsin. "Mr. President," a local reporter asked at the airport, "Karl Hess, who was the principal author of the 1960 and 1964 Republican platforms, has dropped out of society—he is living in a homestead in West Virginia. In the March 25 Rolling Stone, he predicts that we might be witnessing the downfall of the Republican Party. In his words, it is 'abandoning the middle class that it once seemed to so solidly signify' and that it has become the party of the rich and the party of big business. How would you respond to those charges?"

The president replied that the charges could not be true because he had asked Congress to pass a middle-class tax cut. History does not record whether he remembered that evening that Hess had once been among the ghosts putting words in Jerry Ford's mouth.

That wasn't Hess' only cameo in the election. During the Democratic primaries, Jimmy Carter's team sounded him out about a campaign job. Hess hadn't given up entirely on elected officials in his left-libertarian years—he ghostwrote a book chapter for Sen. Mike Gravel (D–Alaska)—but it didn't take long to determine that his differences with Carter were too big for that to work.

Meanwhile, McClaughry sent a blistering memo to the Ford campaign, trying to get the candidate to embrace a plan that would blast away bureaucratic barriers to neighborhood-based self-help. This proved about as easy as getting the candidate to grapple with Hess' critique of his party. After Carter beat Ford, McClaughry agreed to serve on Carter's National Commission on Neighborhoods and convinced Reagan to record a radio commentary expressing hopes for the group. Those hopes were dashed: Writing to Hess, McClaughry called the commission "a new chapter in the world history of organizational mismanagement and technical incompetence."

But that broadcast reflected an interesting development. In 1974, McClaughry had started contributing to Reagan's speeches in areas where he had a policy background. Now he was frequently composing Reagan's radio scripts, producing nearly 50. In 1980 he joined Reagan's campaign staff as a speechwriter.

Some of McClaughry's writing for Reagan was what you'd expect from a Republican politician: attacks on the IRS, Cuban communism, and so on. Some was more unexpected, like the script praising Hong Kong anarcho-leftists for their critique of the Maoist regime. ("We oppose all dictatorships, all governments, all forms of statism, and all authority," Reagan quoted with apparent approval.) Or the one about citizen-activists in rural Michigan who found themselves denounced alternately as left-wing or right-wing depending on which arm of the government they were fighting that week. The "real issue can no longer be discussed in terms of left and right," Reagan's commentary concluded. "The real issue is how to reverse the flow of power and control to ever more remote institutions, and to restore that power to the individual, the family, and the local community."

That wasn't an unusual sentiment for McClaughry, who understood that alliances don't always sort cleanly along left/right lines. Once, in the Vietnam era, he found himself on a plane with the conservative Frank Meyer and the anarcho-communist Murray Bookchin; the trio started arguing about conscription, with Meyer apoplectically arguing that a draft was defensible under some circumstances while "right-wing" McClaughry and "left-wing" Bookchin disagreed. But this wasn't the sort of talk people expected from Reagan.

Writing for Reagan had a side benefit for McClaughry, especially after he took that job at the White House: When making the case for a policy, he could quote sentences he had composed for his boss, giving his ideas Reagan's imprimatur. The president was surrounded by people with different agendas, all trying to conjure their own Reagan. And McClaughry joined the conjurers, to the point sometimes of seeming like a conjuration himself. The conservative intellectual William Schambra once gave a speech arguing that Reagan believed in the value of small communities—an emphasis, Schambra later recalled, "then allegedly the exclusive preserve of the left." As Schambra nervously prepared to deliver his contrarian take, McClaughry "materialized at my side. He had read the speech I was about to deliver, and he assured me that I was not in fact delusional, putting into my hands copies of Reagan's speeches that proved it. This is as close as I have ever come to a divine apparition."

McClaughry's great lost Reagan speech was supposed to air on election eve 1980, but a shift in the polls prompted the campaign to drop its plans for a national address and the text was never cleared for delivery. If the broadcast had happened, Reagan would have opened with the story of those neither-left-nor-right activists in Michigan. He would have offered a series of libertarian complaints about intrusive government, and he would have celebrated an assortment of human-scale institutions, including CDCs and co-ops and community gardens. He would have praised the "basement inventors and backyard experimenters" exploring alternative energy sources. Declaring that "a society of landless serfs, toiling on the estate of a feudal baron, could not aspire to either prosperity or freedom," he would have encouraged tenant ownership of public housing and worker ownership of businesses. He would have called for letting people divert some of their taxes to neighborhood projects. At one point he would have quoted Nathan Wright.

It was powerful rhetoric, although—as McClaughry himself would tell you—anyone expecting Reagan to govern that way would have had a lot of disappointments.

Hess didn't care for Reagan, who he regarded as a creature of big business and the military-industrial complex. (After McClaughry published an article that helped sink the presidential campaign of former Texas Gov. John Connally, Hess dropped him a line that praised the piece but also expressed his doubts that Reagan was any better.) But McClaughry's lost speech felt like something Hess could have written. Not the Hess of 1964, cooking up red-meat rhetoric for Goldwater, but the Hess of 1980, preaching a gentle anarchy in the West Virginia hills.

'The Entire Industrial World Is Fracturing'

By this time Hess was drifting away from the left. There never was a formal break, just a gradual disenchantment—there was too much jargon, too much authoritarianism, too many folks whose hatred for the American government had curdled into a hatred for the American people. He started to suspect that the left had removed itself from working-class life about as thoroughly as the right had removed itself from challenging the state. "This was the only country," he complained in 1984, "that ever developed a left-wing movement which had as its only constituency the upper-middle class."

Hess' love of decentralized technologies expanded to encompass the digital world. His vision of that emerging future was rather prescient, though to find that vision you have to go hunting—he never wrote a book about it, leaving his thoughts scattered through an assortment of articles and speeches, the latter often delivered in a loose, improvisatory way. (When Therese travelled with Karl to speaking engagements, she would sit in the front row with "a little flag in my purse that said bullshit. When I thought he was going a little too far, I would just sort of get out that little flag and wave at him, and he would kind of rein in a little bit.") The world he sketched felt at least 10 years ahead of his time, as though he were transmitting from the post–Cold War era.

That's post–Cold War in a concrete, literal sense: Hess saw the Soviets as a paper tiger on the verge of collapse. ("If we could open one McDonald's and get U2 over to play some good rock for them," he announced in 1985, "they would probably subvert them more than anything the CIA could come up with.") He also caught a glimpse of the networked planet that would emerge in the Cold War's ashes. "The entire industrial world," he said in 1987, "is fracturing into smaller, more skillful, and more flexible manufacturing units." He predicted that same year that copyright laws would soon be unenforceable. In an interview with Liberty, he suggested we were "heading toward a more individualistic type of production." Warming to the subject, he added that a "confederation of cybernated machine tool companies could build automobiles exactly the way each customer wants them" and that "all General Motors has going for it now is the U.S. government."

If Therese had been there then, she might have taken that last bit as her cue to pull out the bullshit flag. But if his comment was overconfident, surely it was directionally correct: We were heading toward an age of makerspaces, shanzhai workshops, and long tails. Coming generations, he told Liberty, "will be able to design all the artifacts of their lives to fit their personal lives." Americans were already "designing their families, their relationships with other people in idiosyncratic and highly individualistic ways. That's one reason why the big corporate and state bureaucracies will have to go."

Meanwhile, Hess started calling himself a capitalist again. Indeed, in 1987 he published a guidebook for young entrepreneurs called Capitalism for Kids. (Sending a copy to an old friend, the novelist Rita Mae Brown, Hess declared, "I guess I'm just a free market freak after all.") Granted, the distinction between Hess the capitalist and Hess the anti-capitalist wasn't always obvious. Nine days after he sent Brown the book, he told a Libertarian Party audience that companies should be "de-managed," that he wanted a world of freely federated self-governing workplaces, and that we should repeal incorporation laws. Conversely, his New Left–era denunciations of the capitalist elite often included arguments that they do not have valid claims to their property under the standards favored by people like Rothbard. If he was still hanging onto those right-libertarian concepts in his left period, and if he was still supporting self-managed industries in his postleft period, were there differences?

There were, but they were subtle. For one, his early-'70s self had not only used those Rothbardian arguments against the corporate chieftains; he went through a period of also accepting more conventionally leftist theories of exploitation. Less philosophically but maybe more substantially, he had developed a different attitude toward the rich. When Marcus Raskin inquired about a possible protest campaign for the presidency, the '70s Hess skylarked a platform that included breaking up "every corporation accounting for as much as 2% (?) of production in any field of service, production, or business of any sort." (Parts of the platform feel tongue-in-cheek—it also included a pledge never to set foot in the White House—so take that 2 percent figure seriously, not literally.) The '80s Hess, by contrast, thought there were important differences between more and less entrepreneurial men of wealth, even when those men clearly owed at least a portion of their fortunes to the state. (When Ross Perot clashed with the more bureaucratic-minded suits on the General Motors board, Hess sided with Perot.) And he no longer seemed interested in expropriating anybody. Better to unleash free competition and let it wear the old order down.

'Against the Bolsheviks and the Whites'

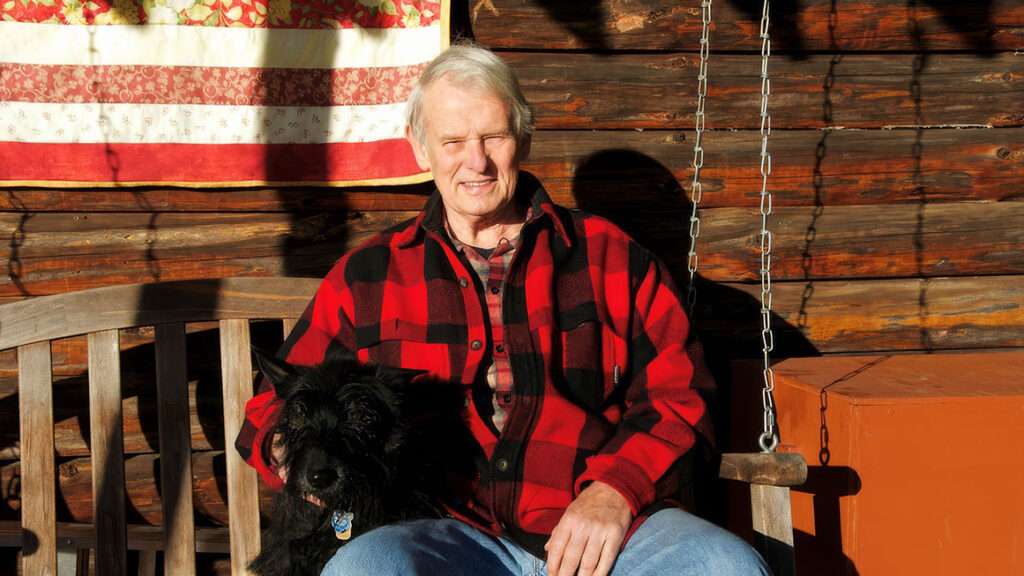

After a couple of decades in West Virginia, where he took up furniture repair, tutored adult illiterates, and edited the only survivalist newsletter ever to publish a Murray Bookchin article, Hess died in 1994. McClaughry is still alive, but he's retired. To read about their careers is to read a series of names, Reagan and Percy and Goldwater, that exist only as historical references.

But it is also to read about men who moved beyond our stale political labels, creating spaces for something more interesting. When Ron Paul was seeking the 1988 Libertarian presidential nomination, Rothbard tried to convince Hess to serve as Paul's running mate, citing his "striking capacity to appeal to both right-wing and left-wing audiences." Hess hadn't left his leftist and rightist selves behind—he had learned from both worlds and incorporated what he liked about each.

McClaughry kept his feet planted on the right, getting a reputation around Vermont as a crusty conservative always ready to tear into regulators. He even managed to get the GOP's gubernatorial nomination in 1992, though this was partly because the party fathers didn't expect to win. But he didn't let that category contain him. He was open to conversation with anyone who seemed interested in breaking down concentrated power, from the New Right stalwarts of the Conservative Caucus to leftists like Alperovitz, Bookchin, and David Van Deusen, an anarcho-syndicalist who for a few recent years improbably ascended to the top of the Vermont AFL-CIO.

Van Deusen and McClaughry kept up a friendly private dialogue, joking sometimes about the mobs that might pursue them if word got out that they were corresponding. For all their disagreements, Van Deusen says, "We both reject and oppose fascism, we both have strong concerns about regressive tax burdens on working people, we both hold a sympathy for the Kurdish struggle in Rojava, and we both believe in a democracy where opposing views can co-exist." And then, invoking a famous three-way struggle between anarchists, Leninists, and the czarist White Army: "If it were 1919 and we were in the Ukraine, we both very well may have rode together with Makhno against the Bolsheviks and the Whites."

I'll bet Hess would have rode along too. Maybe on a motorcycle.

----------------------------------------------------------

* CORRECTION: This originally misstated where the young McClaughry spent his summers.

Show Comments (85)