The Conspiracy Jokers

A new book explores the legacy of the Report on Iron Mountain, while another probes the life of the novelist and essayist Robert Anton Wilson.

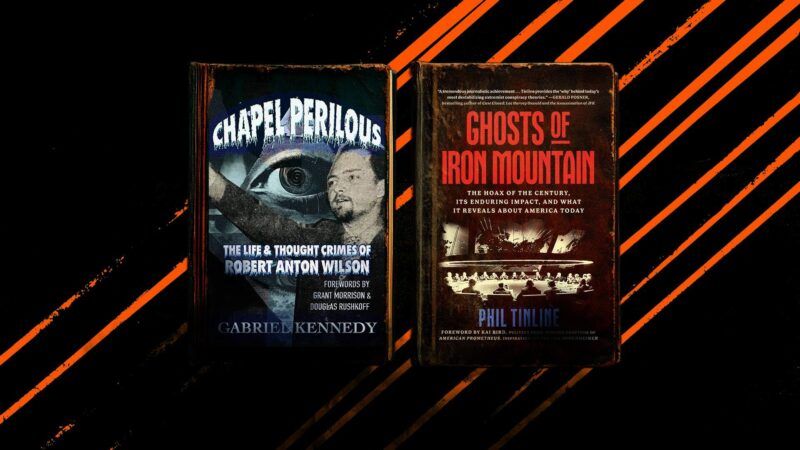

Ghosts of Iron Mountain: The Hoax of the Century, Its Enduring Impact, and What It Reveals About America Today, by Phil Tinline, Scribner, 352 pages, $29.99

Chapel Perilous: The Life and Thought Crimes of Robert Anton Wilson, by Gabriel Kennedy, Media Heist Publications, 288 pages, $29.99

When I was 18, a friend handed me a spiral-bound samizdat manuscript he'd run off at Kinko's. This had once been a secret document, he told me: the report of a government commission that had concluded war was necessary for social stability. Someone had leaked it, and it had been published—but later it had disappeared from stores, almost as though it had been suppressed. Happily, he had a copy, and now I had one too.

The book was the Report From Iron Mountain on the Possibility and Desirability of Peace, and it was, in fact, a hoax. Victor Navasky, the founder of the satiric magazine Monocole, had conceived it after seeing the headline "Peace Scare Drives Market Down"; written in a near-flawless imitation of the bloodless prose favored by groups like the RAND Corporation, it was a cutting parody both of the sentiments that made such a headline possible—"crackpot realism," as C. Wright Mills called it—and of the mandarin class that produced such bureaucratic doorstops. Dial Press had pretended it was a real document when it released the book in 1967, but the primary author, Leonard Lewin, had come clean about its origins five years later. Eventually it had gone out of print, which is why it disappeared from stores.

But I was reading the text in 1988, when one could not simply Google a book's title and learn about such past events. So I read it in a state of uncertainty, increasingly unsure about whether I was encountering a genuinely monstrous document or a very dry joke at the expense of people who write such documents.

Phil Tinline has now written a thoughtful, engrossing, and highly readable history of that dry joke. Ghosts of Iron Mountain does not merely relate how the prank was hatched, executed, and received; it explores the hoax's afterlife, as the document was rediscovered by people who didn't watch that saga unfold in real-time. Not just anarcho-leftists like my friend, but an assortment of right-wing populists with similar attitudes about the officials who send soldiers to die in wars. After the Cold War ended, the book kept circulating in the conspiracy world, where it inspired yet more texts, some from perspectives rather distant from the worldview that inspired the original prank.

But not, perhaps, as distant as you might think. Tinline writes intelligently about the continuities between the New Left of the 1960s and the pan-ideological anti-establishment ethos that embraced Iron Mountain in the 1990s. He recognizes that this conspiracism did not spring from nowhere—that when New Left figures like Mills critiqued the power elite, their criticisms had a lot of substance to them, and that the militia types who rediscovered the Report three decades later were recoiling from some of the same phenomena that Mills rightly opposed, even if some of them were prone to mixing those legitimate fears with nonsense about extraterrestrials or Freemasons.

Or nonsense about Iron Mountain. Yes, Tinline tells us, we have good cause to be wary of powerful people. But we also have good cause to be suspicious of documents that just happen to seem to confirm our worst suspicions. In Tinline's words, you have to "keep an eye on the line between your deep story about how power works, and what the facts support. Between what feels-as-if and what is."

* * *

Around the same time my friend gave me that private-label Kinko's edition of the Report From Iron Mountain, another acquaintance informed me that he had met a member of the Illuminati at a Grateful Dead show.

These days virtually everyone knows what the Illuminati allegedly are—an ancient cabal of conspirators who secretly rule the world, or are secretly trying to take over the world, or in any event are up to something secret, depending on which version of the story you prefer. But in the 1980s they were still semi-arcane, a subject you probably wouldn't encounter without being plugged into one oddball subculture or another. Their name came up at the cafeteria table, and my pal promptly declared that he knew that group: Every now and then, one of them would approach him at a Dead show just to check in on how he was doing and how well he was working toward his innate potential. Then another Deadhead piped up to say that he'd had the same experience. (I was sitting with the hippies that day.)

This time I concluded right away that I was dealing with a dry joke. I just wasn't sure (and I'm still not sure) whether the jokers were the folks at the table, who knew me well enough to know that this might be a funny way to pull my leg, or some person or persons who found it amusing to approach stoners at Grateful Dead concerts and declare that a benevolent order of illuminated beings was keeping an eye on them.

Either way, there was a rich history of joking about the Illuminati, going back at least as far as 1968. That year a group of pranksters conceived of a project called Operation Mindfuck, which involved (among other things) planting absurd items about Illuminati plots in any publication they had access to, from Playboy to Teenset. Two of the Mindfuckers, a pair of Playboy editors named Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea, eventually transformed this Illuminati mythos into a satiric trilogy called Illuminatus!, which appeared in 1975, became an underground hit, and spread satiric Illuminati lore even further.

Wilson in particular became associated with this approach to the Illuminati, and with a host of other topics too. In dozens of books and hundreds of articles (including the occasional small contribution to the publication you are reading right now), he sketched out a psychedelic anti-authoritarian vision that made him an important part of the countercultural intelligentsia: an influence on figures ranging from the "investigative satirist" Paul Krassner to the LSD enthusiast Timothy Leary to the comedian George Carlin to the novelist Tom Robbins (who credited Wilson with converting him to anarchism). The man even inspired a Tammy Wynette single. Yet despite that influence, and despite several worthwhile works of fiction, Wilson himself remained a sub rosa figure, with a cultural status roughly comparable to where his friend Philip K. Dick was before Dick's posthumous breakthrough to the mainstream.

Now at last Wilson has a biography. With Chapel Perilous: The Life and Thought Crimes of Robert Anton Wilson, Gabriel Kennedy has drawn on everything from Wilson's early journalism to his cameos in the Chicago Red Squad's surveillance files. Not just an in-depth look at Wilson's life and career, Chapel Perilous is an ably conducted tour through the many milieus that Wilson passed through—worlds of mystics and atheists, scientists and Playboy staffers, the antiwar and civil rights and libertarian movements. Not to mention pranksters and conspiracy theorists.

If Wilson's work still feels alive and relevant today, nearly two decades after his death in 2007, that may be because one of his favorite topics was the breakdown of consensus reality—or rather, the breakdown of the illusion that your tribe's reality-tunnel was ever universally shared. One way Wilson made that point was a literary technique he called guerrilla ontology: mixing the true, the false, and the unknown to such a degree that, in Wilson's words, "the reader must decide on each page 'How much of this is real and how much is a put-on?'" When readers find themselves in that situation today, we call it "being online."

Iron Mountain was, in its way, an act of guerrilla ontology. And so, I suppose, was my friend's account of his conversation with the Illuminatus at the Dead show. Unless, of course, the Illuminati really did haunt the parking lot outside a rock concert. Gotta keep an open mind, right?

Show Comments (5)