The Most Controversial Paper in the History of Psychedelic Research May Never See the Light of Day

Researchers gave psilocybin to two dozen religious clergy. Was it guided by science, religion, or some awkward combination?

Rick Doblin had come to believe that psychedelic experiences are the "common core" of all religions, and he wanted to test this thesis. In February 1984, the 31-year-old college student living off a trust fund in Sarasota, Florida, typed out a letter to the United Nations, proposing a study that would double as a "training program for a variety of religious ministries." He needed only 50 volunteers, he said, plus a panel of scholars and religious mystics (including His Holiness the Dalai Lama) to judge the results.

Doblin reached out to several politicians for help too. He even wrote a letter to Pope John Paul II. In the meantime, he took on what might have been an even more daunting task, though today it sounds almost mainstream: turning MDMA into medicine.

Beginning in 2015, another psychedelic visionary, Roland Griffiths, initiated a research project nearly identical to what Doblin envisioned. A collaboration between the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and NYU Langone Health, Griffiths' experiment gave psilocybin to two dozen "religious professionals"—Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, and Muslim clergy—on two separate occasions.

What happened is still mostly a mystery, as the paper has yet to be released. Just as the finishing touches were being finalized, Griffiths was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer. At the same time, a controversy was growing in his lab that threatened to derail the psychedelic renaissance. The accusations centered on alleged misconduct involving the religious professionals study.

Five months after Griffiths died peacefully at his home in October 2023, The New York Times published a bombshell exposé that called the study's integrity into question. The article drew on two ethics complaints filed by a former protégé, a psychologist named Matthew Johnson whom Griffiths had groomed to be his replacement.

Griffiths, Johnson said, had been running his research lab less like a laboratory and more like a "'new-age' retreat center," recommending spiritual literature to volunteers and allowing politically aligned funders to work directly on studies. These funders were also paying for projects aimed at introducing various religious communities to hallucinogens. The line between research and advocacy, he argued, had disappeared.

Johnson also accused Griffiths of infusing his research with his own spiritual beliefs and advancing a political agenda aimed at spreading the use of psychedelics. All this, Johnson said, created a "cult-like atmosphere."

The release of the religious professionals study was put on a permanent hiatus. Since then, more information has emerged about Griffiths and the researchers around him, shedding light on an ambitious plan to revitalize Christianity by incorporating a psychedelic sacrament.

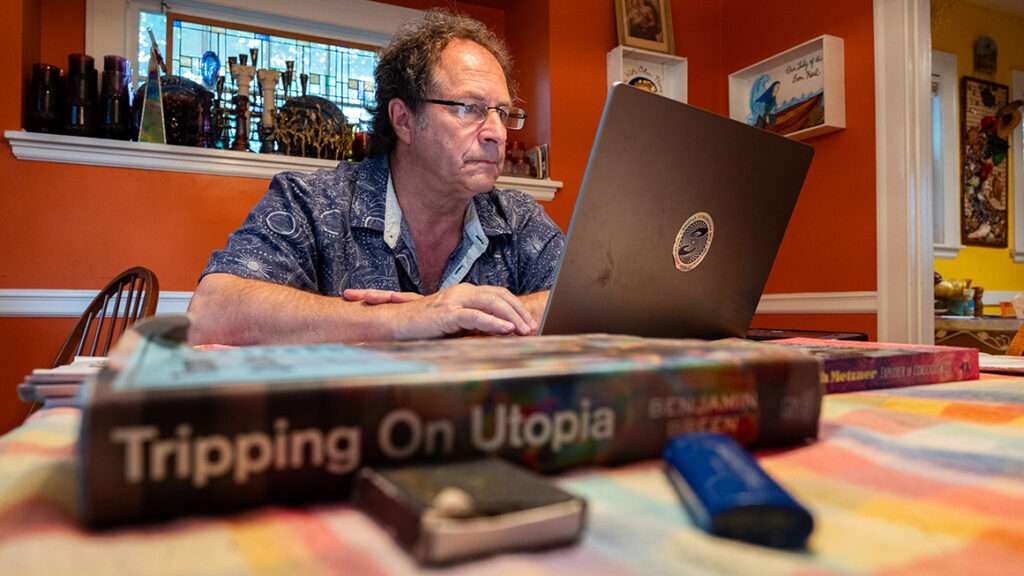

Doblin, who is now the president of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, thinks the unreleased study might be the most important research paper in psychedelic history. It will be a "terrible, terrible tragedy" if it is never released, he says. "I felt that it had the greatest political implications." He blames the delay in publication on fears "that it might spark a fundamentalist backlash against psychedelic research."

But the paper itself, he adds, doesn't "speak to this whole issue of the common mystical core. They avoid the kind of political benefits that I think could come from this understanding that religions are like languages. We all speak different languages but they're coming from the same basic source."

This idea—that there is one truth and one universal core to all religions—is the heart of Perennialism, a school of mysticism with a long history. Doblin is not the only person in the psychedelic world who is fascinated with this concept: It has turned up, well, perennially, in numerous scientific papers as well as a dubious but popular recent book called The Immortality Key. The idea's influence raises an important question about the renaissance of psychedelic studies: Are these researchers guided by science, religion, or some awkward combination?

'This Work Can't and Won't Go There'

Roland Redmond Griffiths was the avatar of a new generation of straitlaced scientists said to be bringing fresh blood, rigorous standards, and a cautious approach to an area of research tarnished by political antics and reckless evangelism. The scion of the same blue-blood family that produced President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Griffiths was the psychedelic counterculture's dream spokesman: a clean-cut "scientist's scientist," so conservative that he once admonished the soft drink industry for "being in denial about the role of caffeine in their products."

Griffiths' career path took a left-hand turn when he was introduced to meditation and psychedelics. Bored with his research on opioids and tobacco, he started meditating regularly in the early '90s with a girlfriend who was a part of the new age scene. ("She believed a bunch of stuff I didn't believe," he later told me.) After a weeklong retreat, he found himself intrigued by the revelatory insights occasioned by mystical states of consciousness. When he was recruited by a sect called the Council on Spiritual Practices—the group's members have included Jordan Peterson, Ralph Hood, Willis Harman, Walter Houston Clark, and other psychologists interested in comparative mythology—Griffiths became the public face of an ambitious project to "make the mystical experience more available."

After reading works on Jungian psychology, Christian mysticism, and Perennialism, Griffiths slowly began to abandon his earlier commitment to the beliefs of B.F. Skinner, a psychologist who taught that behavior could be altered only through modification of the external environment. He started exploring the internal transformations described in the world's esoteric literature, and the life-altering "conversion" experiences described in the New Testament and other holy books.

These texts, along with the works of Harvard psychologist William James, suggested to Griffiths that an unknown biological energy—perhaps entering through the "subliminal trap door of the mind"—might be responsible for these experiences. If scientists could study them systematically in a lab, they might be able to isolate this force, analyze it, and harness its therapeutic benefits. What if science could cultivate trance states via psychoactive plants, sensory isolation, and music, reducing spiritual enlightenment to a systematic process easily accessible to all?

A 2006 press release from Johns Hopkins' media team—headlined "Hopkins Scientists Show Hallucinogen In Mushrooms Creates Universal 'Mystical' Experience"—captured Griffiths' mood. Acknowledging what he called the "unusual nature" of his research, Griffiths preempted any suspicion that science might be probing into the sacred domain. "We're just measuring what can be observed," Griffiths said. "We're not entering into 'Does God exist or not exist.' This work can't and won't go there." A Q&A attached to the press release expanded on this concern, assuring the scientific community that this "God pill" was notgoing to replace religion.

Doblin believes that the spiritual and medical aspects of psychedelics are so closely entangled that they're impossible to separate. Because Griffiths' primary finding was a link between religious experience and marked increases in well-being, the religious connotations of his work cannot be avoided. In fact, Doblin says, studies into the therapeutic benefits of psychedelics have all been "leading up towards" the religious leaders study. The psychedelic movement, he believes, is the vehicle for a "transformation in consciousness that humanity needs to make," one he compares to the "Copernican-Galileo revolution."

While Griffiths and Doblin frequently argued over strategy, their core beliefs were similar. Both were convinced that psychedelics are critical to the survival of the human species, a tool that can be used to "awaken" humanity to impending ecological catastrophe or nuclear war.

"It is a way to spiritualize people en masse, but starting with people in religious traditions," Doblin says. "This is why I felt that Roland's study—the religious leader study—had the most important political implications of all of the psychedelic research."

A 'Holy Meeting'

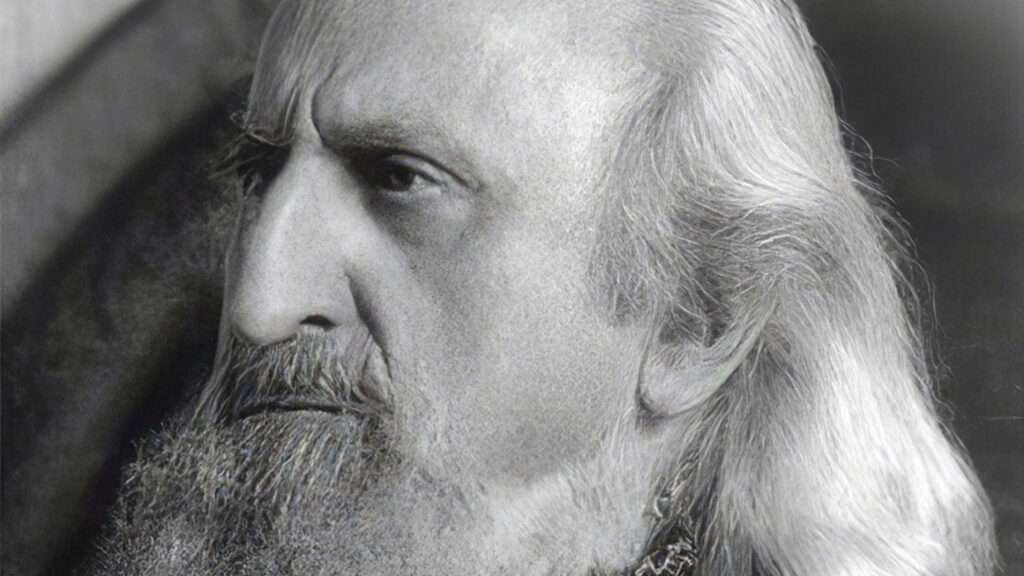

The Perennialist ideas in Griffiths' research are drawn from Forgotten Truth, a book published in 1976. Written by a religious studies professor named Huston Smith, the author was a disciple of a little-known Swiss writer named Frithjof Schuon who, in the 1980s, led a Sufi order based in Bloomington, Indiana.

Though Aldous Huxley was more widely read, Schuon crystallized an "intellectual version" of Perennialism that permeated the psychedelic literature, says Hugh Urban, a scholar of new religious movements at Ohio State University. "Forgotten Truth is where Smith articulates his version of Perennialism most clearly. And that book is just Schuon for the public."

Blending the teachings of the Oglala Lakota medicine man Black Elk with Christian imagery and hardline Islamic mysticism, Schuon taught his followers that the further civilization drifted from the one eternal truth, the more intensely it would descend into chaos and disorder. The ultimate goal of history, he said, was the uncovering of the transcendent unity of all religions and a "New World Order" of which he was the prophet and avatar.

Schuon's group attracted unwanted attention when the eccentric guru was accused of using his authority to satisfy his carnal desires, and it disbanded in 1991.

"Schuon's basic philosophy," Urban says, "is that there's one truth, one universal core to all religions. And at the outer level, the exoteric, all religions are very different, but the closer you get to the inner core, the closer they come. So from his perspective, you could blend them together because the closer you get to this universal truth, the more similar they become." Urban thinks Perennialism appeals to psychedelic enthusiasts because it suggests that "one can tap into the same universal Truth known to the mystics of all ages simply by taking a drug and without the need for the trappings of institutional religion."

Not everyone involved with the study subscribes to such beliefs. Johnson, the former protégé who filed the ethics complaints, thinks the findings have been exaggerated and taken out of context. "Some people want to see the results as validating the Perennial Philosophy," he says. "But it can't."

"I really don't agree that the implications are especially profound," he adds. "Religious professionals who are willing to participate in a psychedelic study tend to respond like others. A solid and publishable finding, but nothing too surprising. I think there was too much of a push to frame this as a magnum opus and a breakthrough on the spiritual effects of psychedelics."

Johnson has warned his colleagues of conflating religion and science. Like any other spiritual tradition where certain individuals—be it gurus, priests, or yogis—claim to have direct access to God, he argues, you are setting up a potentially dangerous situation: "Don't be surprised when you get the sexual abuse of minors or whoever else because of that sacred power."

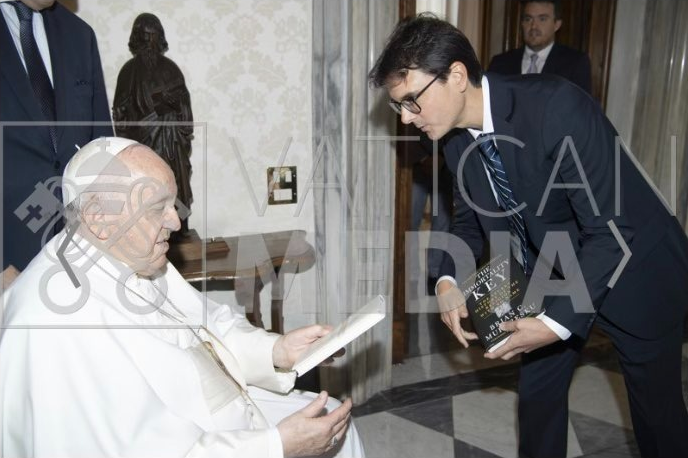

Griffiths, on the other hand, was convinced that he made a groundbreaking scientific discovery with enormous cultural implications. His involvement with activity outside the scope of his official research included a "Holy Meeting" at the Vatican where one of his associates—a lawyer named Brian Muraresku—presented Pope Francis with a manifesto for a psychedelic "New Reformation."

The scientists conducting the religious professionals study discussed details of the meeting through text messages, which included a watermarked photograph of Muraresku—part of the inner circle of Hopkins researchers—preparing to hand the pope a copy of his 2020 book The Immortality Key, which argues that psychedelics might rescue a "dying faith" and save Western civilization. The book also claims that Christianity began as a spinoff of pagan mystery cults that used a hallucinogenic fungus in their most sacred ritual, which purportedly evolved into the Christian ceremony of communion. (Many people depicted in this supposedly "groundbreaking" book on psychedelics and religion are now speaking out against it. More on that here.)

While it's not clear whether the pope has actually read Muraresku's book, the Vatican did recently host a conference featuring a talk on psychedelic science. In September, a controversy broke out when Pope Francis expressed an idea akin to Perennialism: "Every religion," he said, "is a way to arrive at God."

Behind the scenes of the study, Muraresku was also involved with Ligare, a Christian missionary organization launched by a Hopkins clinical trial participant named Hunt Priest—a pastor and former Delta Airlines marketing executive—focused on introducing various Christian communities to psychedelics.

'He Did Have His Blind Spots'

Since the investigation, there has been a notable silence from Griffiths' inner circle, though Hopkins has cut several of his core team members loose.

One of those who departed—Bill Richards—wrote the original protocol for the religious professionals' study and was Griffiths' right-hand man for many years. The 84-year-old psychologist claims to be unaware of what the investigation was really about. The paper, he insists, simply indicates that professional religious leaders can have religious experiences that are helpful to them. "What's the big deal about that? Why should that be controversial? I just don't understand it."

People from different spiritual traditions around the world, he says, "all report this unitive mystical consciousness."

"I'm convinced it's just part of our makeup, that within us is this great unity. And of course, within the unity is intuitive knowledge. And part of the unity of that knowledge is what the Hindus call the bejeweled Net of Indra, or the Unity of Mankind, or that everyone is ultimately connected to everyone else, which has profound implications for ethics and world peace, you know?"

Griffiths' problems with his subordinates, according to Richards, mainly centered on issues of control. "As much as I love and appreciate Roland, I would say he did have his blind spots, and I think he had difficulty empowering others. He could be very devaluing of the clinical dimension and very preoccupied with the statistics. Those numbers made him excited." According to Richards, his friend would be there all by himself on Saturdays, completely absorbed in his work, an aloofness that caused problems in earlier marriages. "Roland was working hard to get the last studies published and so on, almost up until he entered a coma. He was preoccupied with the most pedantic little details of manuscripts."

Though the two have been criticized for infusing scientific research with their own Perennialist beliefs, placing religious objects in the session rooms, and blessing participants with greetings of "namaste," Richards is unapologetic (people in India say namaste "on the street constantly," he objects) and stands behind the religious implications of his and Griffiths' work.

"I think we are participating in an expansion of consciousness, a spiritual awakening, an evolution of what we call normal," he says. There is no way to separate psychedelic therapy from its spiritual nature nor from the reality of our interconnectedness, he argues. He also suggests that the Food and Drug Administration incorporate philosophers and scholars of comparative religion into their advisory panels.

Richards also told me that Sacred Knowledge—his semi-autobiographical book, which doubles as a Perennialist manifesto—has now been translated into 10 languages. He also claimed that Muraresku had "smuggled 10 copies" of the book into the Vatican. Muraresku, who by Richards' account "just appeared in my backyard one day," is "a wonderful guy," Richards says. "He looks like this uptight conventional lawyer in the daytime and turns into Indiana Jones at night."

Ralph Hood, a psychologist who belongs to the Council on Spiritual Practices, also thinks that the controversy has been oversimplified and misinterpreted by people with no personal experience with psychedelics. The world's preeminent scholar of Appalachian serpent handling sects, Hood created a measurement scale that was widely used in psychedelic research; he also helped launch the studies at Johns Hopkins.

Hood, who at 82 is still teaching at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, has been criticized for importing Perennialism into psychedelic research. He denies that, and he also rejects the idea that Griffiths was infusing spiritual beliefs into his research. To the contrary, Hood says, the chief problem with psychedelic research is that the people studying mystical experiences "exclude the possibility that these are genuine spiritual phenomena."

There is a problematic and unquestioned assumption built into science, Hood says: the idea that the experience of transcendent and alternate realities is either delusional or proof of mental illness. What if there is, beyond the capability of the human senses, an "invisible order" that science cannot penetrate? These discriminatory attitudes—an unwarranted bias against religion—preclude the possibility of real innovation, rendering psychedelic research a futile endeavor. Griffiths, following in the footsteps of William James, remained open to these possibilities, leading some to accuse him of dabbling in occultism.

"William James fought back against the licensure of the professions. They're used to exclude, he said, not to include. So they give you a more restricted range of options, not the broader range that we need."

To make psychedelics a mainstream medicine, Hood argues, regulators are seeking a safety that will miscategorize psychedelics as antidepressants and destroy innovation. "The culture is looking for a type of safety that is actually life threatening," he says, "because it doesn't allow you to do what's really important in the long run. So the safe option is very often the worst option….You're not going to fall off the bike if you refuse to ever ride one."

The voices of the volunteers themselves, he adds, are being "effectively silenced" when they are told their experiences are not true. "It's extremely limiting and focused on one aspect of something and therefore falsifies the reality of phenomena."

In the wake of the controversy surrounding the religious professionals study, some scientists are shying away from the mystical experience construct—part of an effort to purge their work of Perennialist influences and distance themselves from anything that feels new age. By backing away from the Jamesian tradition, Hood argues, they're shooting themselves in the foot.

Hood is generally hopeful about the future of psychedelic research. "The danger," he says, "is it's going to be turned into a money-making machine, because the access to sacraments is going to be through prescription and then through pharmacies, and that's going to be a huge failure."

I am skeptical that researchers will offer a purely scientific explanation for the mystical experience anytime soon, as current methods hardly begin to reveal the hidden mechanics behind the bizarre episodes that people like Hood and Griffiths study. For what it's worth, Griffiths felt the same way. "Reductionistic materialists would say, well, this ultimately boils down to brain network changes," Griffiths told me in 2023. "But the level of complexity there far outstrips anything that we can possibly measure. So we're at our infancy in terms of understanding the neuroscience. Our ability to measure what's going on in the brain is incredibly primitive….All we can do is start guessing at it, and then using different frames of reference to explain it."

'You Were More Right Than I Was'

And what about Doblin, the man who dreamed four decades ago of something like Griffiths' study? That experiment, he says, is the very last thing that he and Griffiths discussed before the latter's death. By Doblin's account, Griffiths had had a change of heart about their strategic disagreements and recognized his approach as overly cautious.

"He said, 'You were more right than I was about the importance of drug policy reform, and I was too conservative to object to these things,'" Doblin recounts. "I feel like he had come to see that it's about changing culture as well as doing the science. If you don't change the culture, then you can't even do the science."

Ever the visionary, the 71-year-old Doblin is still looking for opportunities to merge religion and medicine. On a recent trip to Spain, an incense holder suspended from an enormous dome with ropes in the Cathedral of Santiago caught his eye. "And they could swing this incense holder to spread it throughout the church. But, I said, it was inactive wafers. So I think distributing these things through religion would be a really good idea if people were encouraged to really explore more, to tap into this Perennial philosophy."

I asked him whether he would attempt to resurrect his U.N. proposal from 1984. He smiled and said no. "I think we're too wrapped up in trying to make MDMA into a medicine to see what that involves."

Show Comments (33)