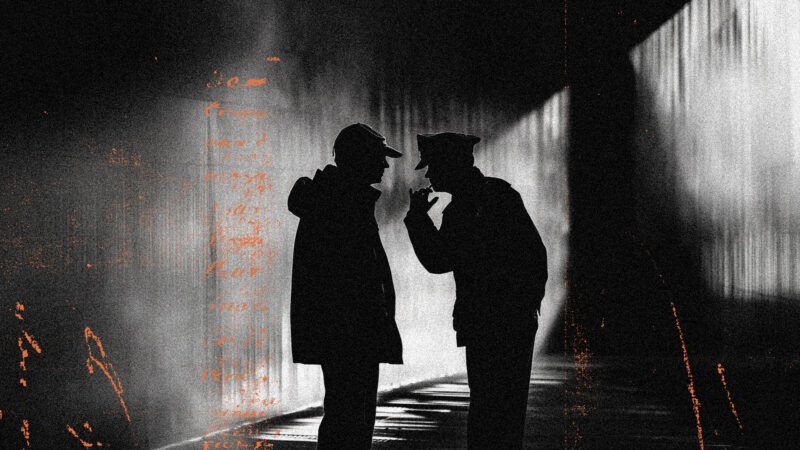

State 'Bias Response Hotlines' Encourage People To Snitch on Their Neighbors for 'Hate Speech'

By the end of 2025, as many as 100 million Americans could live in a state where they can be reported for protected expression.

By the end of this year, as many as 100 million Americans could live in a state where they can be reported to a "bias response hotline" for a wide range of protected speech. While states claim that these reporting mechanisms don't punish people for non-criminal speech acts, many also claim to attempt to stop hateful speech incidents "before they occur."

According to a recent report in The Washington Free Beacon by reporter Aaron Sibarium, these reporting systems allow people to "snitch" on their neighbors. Connecticut allows people to report "hate speech" they "heard about but did not see." Vermont encourages citizens to call the police over "biased but protected speech." Philadelphia actually directs people to give the names of alleged offenders so they can be contacted.

"If it is not a crime, we sometimes contact the offending party and try to do training so that it doesn't happen again," Saterria Kersey, a spokeswoman for the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, told Sibarium.

Oregon's Bias Response hotline encourages citizens to report not only hate crimes, but also "non-criminal hostile expression motivated in part or whole by" someone's protected identity. These incidents can include "hate speech," "displaying hateful symbols or flags," and "telling or sharing offensive 'jokes' about someone's identity."

What happens when someone calls this hotline? The Free Beacon called the hotline and reported a fictional incident—a man, identifying himself as a Muslim said that he felt "targeted" by his neighbor's Israeli flag.

"Within 20 minutes, a hotline operator had logged the display in a 'state database,' referred to it as a 'warning sign,' and suggested installing security cameras in case the situation 'escalates,'" Sibarium writes. "He also informed this reporter that, 'as a victim of a bias incident,' he could apply for taxpayer-funded therapy through the state's Crime Victims Compensation Program, which covers counseling costs for bias incidents as well as crimes."

Even though nothing criminal had allegedly occurred—or even something that could be fairly described as objectively offensive—the operator nonetheless treated the report with immense gravity.

"Even if it is not very explicit, we go with whatever the victim is experiencing," the operator said during the call. "And if your sense is that this is based on discrimination against your faith or your country of origin…that's how I would document it."

Sibarium notes that, while many states use their reporting systems to direct callers to state-funded counseling services, many also use these hotlines as a kind of "predictive policing," tracking reported speech incidents and using them "as data points that are used to predict hate crimes."

It's not clear how much, if at all, these systems violate the First Amendment. While states say they don't punish reported individuals—and often, don't keep their names stored—for alleged "hate speech," it's likely that these hotlines don't explicitly violate free speech rights. However, it's not hard to see how such wide-ranging bias response hotlines could end up chilling protected speech.

"The ability to speak freely is core to our democracy. Any system or protocol that stifles or inhibits free expression is antithetical to the principles and ideals of our institutions of higher education and our republic," Angel Eduardo, a senior writer and editor at the Foundation For Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), a First Amendment group, wrote in a blog post earlier this week. "In both word and deed, bias reporting systems fundamentally undermine these principles — and now seriously threaten the First Amendment rights of…ordinary citizens."

Show Comments (41)