Just What the CEO Shooting Needs: A Video Game Moral Panic!

NBC reports the assassin's video game habits, as if they matter.

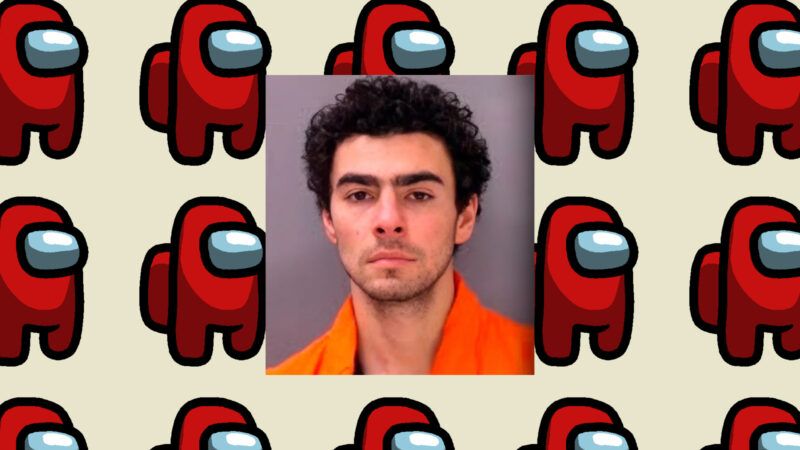

On Monday, police arrested Luigi Mangione, suspected of being the gunman who killed UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson last week. Right away, the internet scoured Mangione's online presence, deducing numerous details about his life (a privileged Ivy League graduate in the tech world) and his potential motive (a painful and debilitating injury). But NBC News offered an odd theory of its own.

"Luigi Mangione, who was arrested and charged with murder in the shooting death of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson, once belonged to a group of Ivy League gamers who played assassins," the article begins. "In the game, called 'Among Us,' some players are secretly assigned to be killers in space who perform other tasks while trying to avoid suspicion from other players."

If that feels like a particularly weak parallel to draw, it should.

Among Us is an online multiplayer game rated for players aged 10 and up, based on its "fantasy violence" and "mild blood." It's also very popular, and not just among violent vigilantes: The game has over 150 million registered users and averages more than 10 million active users each day. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D–N.Y.) even played Among Us on an October 2020 livestream. Clearly, one's interest in a very popular party game is not an indicator of future criminal violence.

The NBC News article nearly admits as much, noting that the "child-friendly" game "has been wildly popular, especially during the pandemic, and particularly among young children because of its simple mechanics, colorful cartoonish nature, and unpredictability."

To be clear, NBC does not say that Among Us is to blame for Mangione murdering a health insurance executive; it merely quotes a college acquaintance who found it "ironic" that someone he primarily interacted with in the context of a game featuring killers would, himself, end up a killer.

And sure, there's some dramatic irony in that sequence of events. But it certainly doesn't rise to the level where it should lead a major national news network's write-up of the suspect's arrest.

In fact, multiplayer video games in which players kill each other have long been a popular pastime: Earlier generations would gather around TVs to play Halo or GoldenEye 64 against each other. The coffee table book LAN Party, released earlier this year, depicts numerous multiplayer gaming sessions from the early 2000s.

Even apart from the digital space, Among Us follows the same basic format as numerous card games: Partygoers since the 1980s have played Mafia, in which some players are deemed "civilians" and others are deemed "mafia," and each team tries to suss out and kill the other.

Instead, NBC's decision to choose the video game anecdote as the focal point of its article is reminiscent of the numerous times violent video games have shouldered the blame for real-world violence.

The most prominent example is the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. "Many commentators and some parents are wondering aloud about what influence—if any—video games may have had on the actions of the two gunmen," The New York Times reported just days later, noting that the pair were fond of first-person shooters Doom and Quake. Lawmakers have tried to either ban or severely limit the sale of violent video games, only to be struck down by courts for violating free speech.

Even as far back as 1976, the arcade driving game Death Race allowed players to run over screaming civilians. The gameplay was primitive and the graphics looked more or less like Pong, but a representative of the National Safety Council complained to the Times that the game could lead to violence: "I shudder to think what will come next if this is encouraged. It'll be pretty gory."

"Research clearly suggests that exposure to violent video games temporarily increases a person's hostility," Villanova University psychology professor Patrick Markey wrote in 2013. "However, research does not show a clear link between playing violent video games and real world violence. Although researchers have often noted the preference of violent video games by many school shooters, given that 97 percent of adolescents play video games such a preference is not overly surprising." Research conducted in the years since has further disputed the link between video games and violence.

And yet the claim has persisted, cited both by President Barack Obama and by President Donald Trump after mass shootings during their respective tenures in office.

Again, perhaps NBC did not intend to imply a direct correlation between two unrelated events. But in choosing to lead its coverage of Mangione's arrest with the tidbit that he once enjoyed playing a particular video game, the outlet appears to be playing into age-old tropes that a ubiquitous activity enjoyed by millions is actually some pernicious force of evil.

Show Comments (46)