Washington Sued for 'Racially Conscious' Homeownership Program

Washington's Covenant Homeownership Program excludes certain applicants on the basis of race.

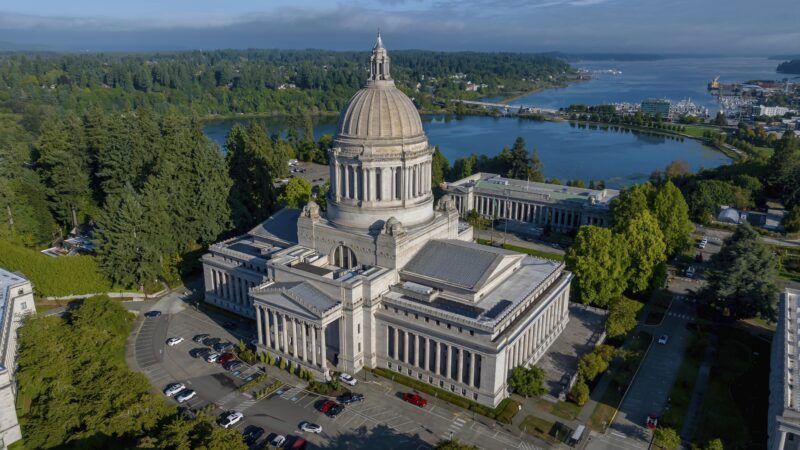

The Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR) submitted a complaint on Tuesday against the Washington State Housing Finance Commission (WSHFC) for its Covenant Homeownership Program, which explicitly bars certain applicants from eligibility on the basis of race. The commission cites the 2024 Covenant Homeownership Program Study as empirically justifying its "race-conscious" special purpose credit program, but it's unlikely to pass strict scrutiny.

The Washington State Legislature passed the Covenant Homeownership Act in May 2023 to remedy "past and ongoing discrimination and its impacts on access to credit and homeownership for black, indigenous, and people of color." Past discrimination includes 50,000 clauses in home deeds and homeowners associations that were used "between the 1920's and 1960's throughout Washington state to restrict housing based on race, religion, and ethnicity," according to the commission. The Covenant Homeownership's special purpose credit program offers certain first-time homebuyers a zero-interest rate loan for downpayment and closing cost assistance to address discrimination and reduce the racial disparity in homeownership.

The program raises its revenue by collecting a $100 document recording assessment for real estate transactions, which the commission projected will "generate between $75 million and $100 million each year." The program is restricted to those Washingtonians whose ancestors (or themselves) were subjected to state-based racial discrimination in housing contracts before the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Further qualifications for the program include earning the area's median income or less, being a first-time homebuyer, and either being or having an ancestor who was Hispanic, Native American, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander, Korean, or Asian Indian and lived in the state before April 1968. Limiting access to the program's special purpose credit program in this way "facially discriminates on the basis of race," according to the complaint.

WSHFC acknowledges the program's racial requirements, describing it as going "beyond 'colorblind' or 'race-neutral' assistance" to allow Washington "to directly remedy the harm caused by its discriminatory policies." Although the commission insists the program "does not represent a formal reparations effort," the United Nations, whose definition the commission cites, disagrees. One of the U.N.'s four reparations measures is "compensation…provided for any economically assessable damage, loss of earnings, loss of property, loss of economic opportunities, [or] moral damages."

The Covenant Homeownership Program Study, published by the National Fair Housing Alliance, a nonprofit advocacy group that fights housing discrimination, justifies the program's racial discrimination on the grounds that "state institutions played both active and passive roles in perpetuating housing discrimination against a range of marginalized groups." The researchers also considered disparities in homeownership rates in their recommendations for racial eligibility: 68 percent of non-Hispanic white households are homeowners, compared to only 49 percent of Hispanic and non-white households and 31 percent of Black households.

Japanese and Chinese Americans are ineligible for the Covenant Homeownership Program despite the program's study identifying discrimination against both groups: "Anti-Japanese sentiment led to the passage of the 1921 Alien Land Bill by the Washington Legislature," which restricted the ability of Japanese residents "to own and lease land"; and Chinese people were excluded from land ownership by "the prohibition of 'alien land ownership' in the 1889 State Constitution."

Though the Covenant Homeownership Act states its purpose is to remedy past and ongoing discrimination, it excludes certain "Asian subgroups who…have homeownership rates on par with or…higher than Whites." Nonetheless, the exclusion of Japanese and Chinese Americans from the program undercuts the whole rationale of historical injustice, says Joshua Thompson, director of the Equality and Opportunity Program at the Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF), which is representing FAIR in its lawsuit.

Historical discrimination is rightly recognized as evil, as is present-day discrimination, which is unconstitutional except when narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest. Thompson explains that there are only two such interests: "If you need to classify on the basis of race for a short moment to avoid a prison riot…and remedying past discrimination." Though this second interest seems to open the door to race-based programs like Washington's, Thompson explains "that the person receiving the remedy is the person that was injured by the harm." In other words, it is unconstitutional to use race as a proxy for individual injury resulting from illegal discrimination.

The commission describes the Covenant Homeownership Act as "the first programmatic use by a government agency to remove persistent structural barriers to homeownership," but numerous policies have already been enacted at the federal, state, and local levels to decrease inter-group disparities in facially discriminatory ways. Thompson says PLF has around fifty ongoing cases against the preferential treatment of disadvantaged/minority/woman business enterprises for public contracts, racial and gender quotas for state boards and commissions, federal contracts favoring minority-serving institutions, and preferential licensing for certain racial groups, such as marijuana dispensary licenses for black New Yorkers.

One might wonder how these programs can exist at all if they're flatly unconstitutional. The answer is that even unconstitutional programs must be identified and challenged by someone with legal standing—by some particular person or group of people damaged by exclusion from a particular program—in order for courts to prohibit them through a permanent injunction.

Nonetheless, Thompson is optimistic that the continuous game of legal Whac-A-Mole can be ended in the next five years not just through appellate opinions but by changing hearts and minds. Ending race-based policies is "the moral result that will happen eventually," says Thompson, but "it's not going to happen without the work that needs to be done."

Show Comments (55)