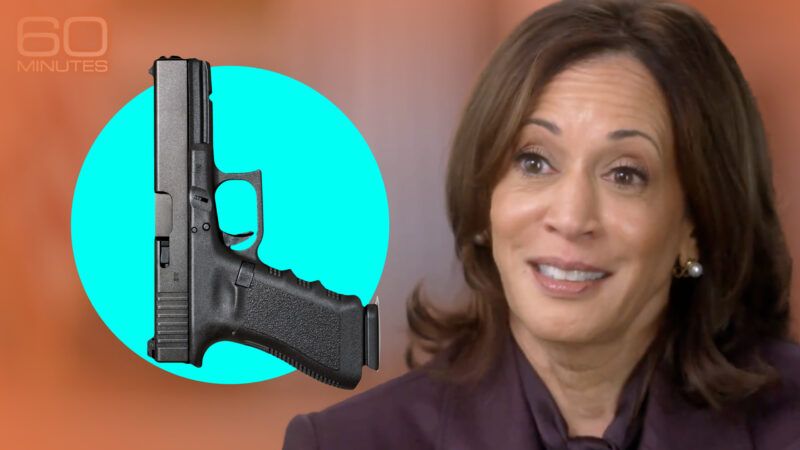

Kamala Harris Says She Owns a Handgun—Despite Fighting To Ban Others From Doing the Same

Journalists should be interested in interrogating this contradiction, should the 2024 presidential candidate continue giving interviews.

When Vice President Kamala Harris appeared in conversation with Oprah Winfrey last month, she dropped a tidbit that may have come as a surprise. "If somebody breaks in my house," she said, "they're getting shot."

It was, or at least it should have been, one of the more relatable things she's ever said. Whatever your politics—Democrat, Republican, Libertarian, Jill Stein groupie, etc.—the right to protect your life and your family when threatened with potentially deadly aggression is something so basic as to transcend partisanship.

It's a bit less relatable, however, when considering Harris' past advocacy against other people accessing the same type of protection she has.

She provided more specifics during her recent 60 Minutes interview. "I have a Glock, and I've had it for quite some time," she said. "My background is in law enforcement. And, so there you go."

That admission should hardly be a bomb drop. But it's difficult to reconcile with her support, as San Francisco District Attorney, for Proposition H, which banned the city's residents from merely possessing (as well as manufacturing or selling) handguns. The ordinance passed in 2005, and a California appeals court threw it out three years later.

Harris hasn't said exactly how long she's owned her firearm. Yet if it's been for "quite some time," as she said, then one can reasonably assume that her owning a gun overlapped with her view that the state should curtail others from doing the same. But the next detail she provided—that she was in law enforcement—possibly provides some context for her position, at least attitudinally, as Proposition H provided gun ownership exemptions for law enforcement, military, and security guards.

Not long after, Harris would also go on to file a brief in District of Columbia v. Heller, the landmark Supreme Court decision that ruled D.C.'s handgun ban unconstitutional and established that people have a right to own a firearm for self-defense, divorced from military service.

That was not the outcome Harris sought in the brief she submitted. Citing past jurisprudence at the time, she said that "the Second Amendment provides only a militia-related right to bear arms," "the Second Amendment does not apply to legislation passed by state or local governments," and "the restrictions bear a reasonable relationship to protecting public safety and thus do not violate a personal constitutional right." Had that view prevailed, the handgun ban in D.C., where she now lives, would have remained intact.

This position may be a bit easier to reconcile. "I don't think there's anything inherently hypocritical or duplicitous about someone owning a gun while also taking the position that the Constitution doesn't protect the right to own a gun," says Clark Neily, who successfully argued Heller as co-counsel, via email. "For example, many thoughtful people think women should be able to have an abortion—and have had or would have an abortion themselves—but nevertheless don't believe there's a constitutional right to an abortion."

The abortion comparison is an apt one, and it's an interesting one to interrogate when considering Harris believes the U.S. Constitution promises a right to one, despite there being no text touching the topic directly. She has not struggled, meanwhile, to argue over the years that gun ownership should be heavily regulated, the Second Amendment notwithstanding.

Neily is still correct, though, that these things are not necessarily inconsistent logically. But it's still worth noting the practical implications: Had the Supreme Court ruled her way, the law would prohibit the people in the city where she lives from having the very sort of gun she now openly acknowledges she keeps to protect her safety—a contradiction that a journalist should be interested in cross-examining at some point during one of her campaign trail interviews, should she continue to give them.

Harris' interests as a prosecutor, it seems, directly contradicted her interests as a private person, and the interests of the little people generally. That discrepancy, if anything, is cause for introspection.

Show Comments (65)