SCOTUS Dodges a Crucial Problem With Disarming People Based on Restraining Orders

The Court says "a credible threat" justifies a ban on gun possession but does not address situations where there is no such judicial finding.

A federal law that Congress enacted in 1994 prohibits gun possession by people subject to domestic violence restraining orders. Since that seems like a no-brainer, many people were dismayed when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit deemed that provision unconstitutional last year in United States v. Rahimi. But as anyone who reads the majority and concurring opinions in that case can see, there is a striking problem with 18 USC 922(g)(8): It disarms people even when there is little or no evidence that they pose a danger to others.

In an 8–1 decision today, the Supreme Court avoided that issue by noting that the man who challenged his prosecution under Section 922(g)(8), Zackey Rahimi, is a bad dude with an extensive history of violence, including violence against his girlfriend. As applied to people like Rahimi, Chief Justice John Roberts says in the majority opinion, the law is "consistent with this Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation"—the constitutional test that the Court established in the 2022 case New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen.

"When a restraining order contains a finding that an individual poses a credible threat to the physical safety of an intimate partner, that individual may—consistent with the Second Amendment—be banned from possessing firearms while the order is in effect," Roberts says. The decision does not address the question of whether it is consistent with the Second Amendment to disarm someone without such a judicial finding.

Noting that Rahimi raised a facial challenge, Roberts faults the 5th Circuit for focusing on "hypothetical scenarios where Section 922(g)(8) might raise constitutional concerns" instead of "consider[ing] the circumstances in which Section 922(g)(8) was most likely to be constitutional." That error, he says, "left the panel slaying a straw man."

As 5th Circuit Judge James Ho emphasized in his Rahimi concurrence, that "straw man" is not merely hypothetical. The "constitutional concerns" to which Roberts alludes derive from the statute's loose requirements for court orders that trigger the gun ban. Under Section 922(g)(8), a restraining order must include at least one of two elements, one of which sweeps broadly enough to encompass individuals with no history of violence or threats.

The first, optional element—a judicial finding that the respondent "represents a credible threat to the physical safety" of his "intimate partner" or that person's child—provides some assurance that the order addresses a real danger, especially since the law requires a hearing in which the respondent has "an opportunity to participate." As Roberts notes, the order against Rahimi included such a finding. But the second, alternative criterion—that the order "by its terms explicitly prohibits the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against such intimate partner or child that would reasonably be expected to cause bodily injury"—can be met by the boilerplate language of orders that are routinely granted in divorce cases, whether or not there is good reason to believe the respondent is apt to assault anyone.

In his Rahimi concurrence, Ho noted that protective orders are "often misused as a tactical device in divorce proceedings" and "are granted to virtually all who apply." They are "a tempting target for abuse," he said, and in some cases have been used to disarm the victims of domestic violence, leaving them "in greater danger than before."

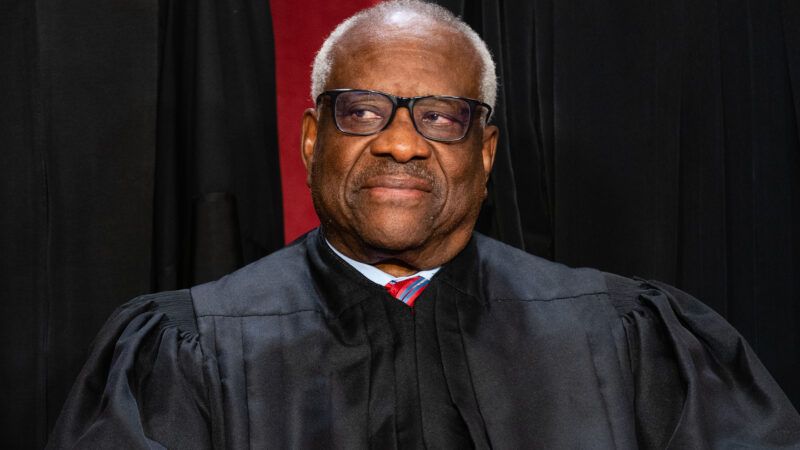

In the lone dissent from today's decision, Justice Clarence Thomas likewise notes how easily someone can lose his right to arms under Section 922(g)(8). The provision "does not require a finding that a person has ever committed a crime of domestic violence," he writes. It "is not triggered by a criminal conviction or a person's criminal history." And it "does not distinguish contested orders from joint orders—for example, when parties voluntarily enter a no-contact agreement or when both parties seek a restraining order."

Furthermore, Thomas says, the law "strips an individual of his ability to possess firearms and ammunition without any due process," since "the ban is an automatic, uncontestable consequence of certain orders." The Cato Institute made the same basic point about due process in a brief supporting Rahimi's challenge.

Although a hearing is required for the restraining order itself, Thomas notes, "there is no hearing or opportunity to be heard on the statute's applicability, and a court need not decide whether a person should be disarmed under §922(g)(8)." He also points out that the penalties for violating the provision are severe: up to 15 years in prison, plus permanent loss of gun rights based on the felony conviction.

Roberts, who criticizes the 5th Circuit for requiring a "historical twin" rather than a "historical analogue" under the Bruen test, sees precedent for Section 922(g)(8) in "surety" laws that required threatening people to post bonds, which they would forfeit if they became violent. But Thomas does not think those laws are "relevantly similar" to the provision that Rahimi violated.

"Surety laws were, in a nutshell, a fine on certain behavior," Thomas writes. "If a person threatened someone in his community, he was given the choice to either keep the peace or forfeit a sum of money. Surety laws thus shared the same justification as §922(g)(8), but they imposed a far less onerous burden."

In particular, Thomas says, "a surety demand did not alter an individual's right to keep and bear arms. After providing sureties, a person kept possession of all his firearms; could purchase additional firearms; and could carry firearms in public and private. Even if he breached the peace, the only penalty was that he and his sureties had to pay a sum of money. To disarm him, the Government would have to take some other action, such as imprisoning him for a crime." Thomas thinks the government "has not shown that §922(g)(8)'s more severe approach is consistent with our historical tradition of firearm regulation."

Roberts, by contrast, says a prosecution under Section 922(g)(8) can be consistent with that tradition, at least when a judge concludes that someone "poses a credible threat to the physical safety of an intimate partner." The constitutionality of applying Section 922(g)(8) in cases where there was no such finding remains uncertain. Some Second Amendment scholars, such as the Independence Institute's David Kopel, argue that the provision would be constitutional if it were amended to require a finding of dangerousness.

The Court did clarify an important point in a way that could bode well for other challenges to the broad categories of "prohibited persons" who are not allowed to possess firearms, such as cannabis consumers and other illegal drug users. The majority rejected the Biden administration's position that only "responsible" people qualify for Second Amendment rights.

"We reject the Government's contention that Rahimi may be disarmed simply because he is not 'responsible,'" Roberts writes. "'Responsible' is a vague term. It is unclear what such a rule would entail. Nor does such a line derive from our case law."

In Bruen and in District of Columbia v. Heller, the 2008 case in which the Court first explicitly recognized that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to armed self-defense, Roberts notes, "we used the term 'responsible' to describe the class of ordinary citizens who undoubtedly enjoy the Second Amendment right….But those decisions did not define the term and said nothing about the status of citizens who were not 'responsible.' The question was simply not presented."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Noting that Rahimi raised a facial challenge, Roberts faults the 5th Circuit for focusing on "hypothetical scenarios where Section 922(g)(8) might raise constitutional concerns" instead of "consider[ing] the circumstances in which Section 922(g)(8) was most likely to be constitutional." That error, he says, "left the panel slaying a straw man."

Since when has Washington ever let that stop anybody ?

I have to side with Justice Thomas on this one.

When I went to College the first time (97-99) I was in a class with a former police officer. After his divorce, his ex-wife claimed that he drew his service weapon and threatened to blow her head off. She was immediately granted a Protection Order. Because of that order he could no longer work as a police officer. He did desk duty while he attempted to get the order dismissed. The Judge refused to dismiss the order and the Police Brass was catching heat from politicians and the media for his being on the force. His Union refused to back him up because they didn’t want the publicity. It was later found that she had made the whole incident up. On the day that she said that it happened he wasn’t even in the State.

I understand the need for some thing like this, but, there is no review system, no system for appeal, no time limit and no penalty for obtaining the order by deception. Judges approve the vast majority of orders because there is no downside for approving one, whereas it if an order request is turned down and something happens it can be political suicide.

I doubt that a judge would rule like that today. After all, nothing is more important than officer safety. Not even the safety of a spouse.

That was a judge with some big fucking balls. I can't imagine the system ever turning on the cops. Maybe the wife got herself a man hating lesbian lawyer who went for the throat.

He said it was pre 9/11. Before then police and other ‘first responders’ were not treated like deities as they are now.

It's so hard to imagine I doubt this story is accurate.

I've known cops who should be barred by Lautenberg from possessing arms still working as armed cops.

Send his monkey ass back to Senegal

Wrong spot.

Drunk already?

As has been noted Rahimi was the wrong plaintiff for bringing this challenge. If you want to make the case that restraining orders can be overused, pick a better person to issue the challenge.

Very good point. There have to be a lot better people who really got screwed unfairly who could make this challenge.

Like Saint Floyd?

Rather than open the door further to prosecuting future-crime, I want to suggest a different radical idea, but one compatible with liberty: the elimination of public spaces.

If everywhere (or at least most places) we go are privately owned, then we either conform to the rules set by the owners, or we leave.

If risk-averse phobics want a gun-free world, let them individually or collectively buy ownership of their domain. They would then be legally (and philosophically) entitled to ban guns and expel anyone who does not comply.

Yup, the mechanics of how we accomplish this are challenging, and we would need to adjust to frequent guest status in many places. Or maybe we adapt club memberships writ large, and formalize reciprocal access rights. In any case, it might be better than living in the Minority Report.

How about an alternative? A couple years ago, I read The Centenal Cycle by Malka Older (the word centenal designates a cohort of 100 people who together agree to join a society under a single set of laws/regs/rules).

Based on your preference of governmental theory and laws, you choose to be a citizen of one, 100-person nano-country—a centenal—which usually chooses to ally with a nation consisting of as many centenals, world-wide, as wish to abide with identical rules.

The most interesting part of the trilogy is in the first book, Infocracy. It fleshes out life in dozens (out of millions worldwide) of different such nations: technocratic; technophobic; theocratic; authoritarian; communitarian; libertarian; libertine; commerce-oriented free-market; communist direct economy; ascetic; atheistic; militarian; ethnicity-based; geography-bound; globally dispersed; dear leader personality cult; 100-member-pure-democracy; single appointed-or-elected representative republic.

Don’t like how your nation treats you? There are low-friction ways for an individual to instantly move to any of millions of others who will take them.

Global power in that world is based on how many centenals vote to join you in either a single-nation government, or in federations of nations sharing basic principles but differing in their specific implementations.

Most of the political plot is based on rivalries among a dozen global-power super-states preparing for the every-five-years elections (managed and results guaranteed by benevolent, capable, future-Google) in which the winner receives specific global powers and responsibilities for the next five years. It’s the only time during which every centenal can decide to switch alliances, and that alliance-switching drives the plot.

So, I'd describe the trilogy as a political cyberpunk technothriller set in a global/local political structure enabled by a logical if unlikely extension of Google/Meta-type technology. It takes what could be just another Big Brother future dystopia (and aren’t we all tired of dystopias?) and, as an assumption underlying and necessary to the plot, changes Big Brother to a morally neutral, fully pervasive, collecting-everything-with-all-info-fact-checked/instantly-accessible-everywhere-to-everyone non-governmental entity.

That organization, named Information, is recognizable as a capable/benevolent future evolution of Google where both the dream-tech and Don’t Be Evil, actually work. Get past the conventions of the technothriller genre, and the global societal political part is interesting. Yes, it does require near-Tolkien-level willful suspension of disbelief.

As to a review, Infocracy (the first book) is inventive world-building supporting a pretty good politics/elections story…kind of All the President’s Men meets Neuromancer. Unfortunately, however, the thriller aspects start sending the plot downhill in book two, to a total crash-and-burn in book three.

Total words could have been cut in half—potentially resulting in one very good book—a problem not uncommon with writers starting with an assumption of a trilogy so they can sell three books instead of one.

You'd probably be interested in the first book, as inventive speculation on your challenging mechanics of how "we either conform to the rules set by the owners, or we leave...let them individually or collectively buy ownership of their domain." It's fine to finish there...go to books 2 and 3 at your risk.

That is a fantastic series. I highly recommend it.

Where are the trumpists?

Clarence says, "Me want free, me want free!"

NardZ, tell your triplets to get to work! The racist scum will fall inline behind them.

Your very racist

Someone flunked Supreme Court 101. The law being challenged does require an individualized determination of the facts and a credible allegation of danger from the subject of the restraining order. And it's only for a limited time period.

Sullum should know the court isn't going to "address situations where there is no such judicial finding" if it wasn't an issue in this case.

But they did say it has to be an individualized determination by a court in both the Chiefs opinion and Gorsuch's concurrence.

That's the problem: "An individualized determination" is very different indeed from "A conviction by a jury of your peers".

The Court majority has now legitimized stripping people of rights, formerly only a consequence of a felony conviction, by judicial fiat. Scratch the right to a jury trial.

The Second Amendment is a fundamental right under our Constitution and only extreme overriding circumstances – proven in court to be an actual and imminent danger – should be allowed to remove that right. Harming another individual except in self defense or the reasonable defense of others; or threatening to harm others, is a crime. A restraining order is a civil order not requiring the level of evidence required under due process to charge or convict a person of a crime and, therefore, does not rise to the level of due process to take away that person’s rights under the Bill of Rights. Although it does not surprise me that Roberts and the other socialists on the Court look for any shred of an excuse to erode the second amendment, it does surprise me a bit that so-called “conservatives” took the bait here! If a person threatens another person with harm there is no reason whatsoever for the District Attorney not to investigate that crime and if the suspect is charged with the crime then the suspect might reasonably lose such rights temporarily until found guilty or not guilty, regardless of some restraining order.

Zackey Rahimi, is a bad dude with an extensive history of violence, including violence against his girlfriend.

If he's such a bad, violent dude, why has he never been convicted of a violent felony -- felony prohibition on firearms ownership would make one tied to the restraining order moot.

If I understood the story correctly Rahimi has been convicted of those crimes, but the one in question here was not one of them. It's a technicality that turns out to be more important than the actual facts of this particular culprit. The law itself is an example of overreach that needs to be struck down. No one has seriously questioned the Constitutionality of removing the second amendment rights of convicted felons in prison or (maybe) parole.

Three things I will note.

- while many have pointed out the due process deficiencies of imposing collateral consequences based upon restraining orders from state courts, this case did not involve due process.

- another issue is whether or not Congress actually had subject matter jurisdiction to enact this law. Unlike states, Congress lacks a general police power. Specifically, Article I does not give Congress general subject matter jurisdiction over intimate partner violence. Nor does it give Congress power to impose collateral consequences to reinforce state court restraining orders. The only clear jurisdiction the feds have over state court restraining orders would be to review them if challenged on federal legal grounds. However, while Rahimi and some amici argued this, Rahimi did not argue this in the courts below, so SCOTUS passed on this question.

- it appears if a state were to temporarily prohibit persons subject to these orders from engaging in any form of intimate contact or relationship while these orders were in effect, then a facial challenge to such a prohibition would fail under this opinion.