SCOTUS Dodges a Crucial Problem With Disarming People Based on Restraining Orders

The Court says "a credible threat" justifies a ban on gun possession but does not address situations where there is no such judicial finding.

A federal law that Congress enacted in 1994 prohibits gun possession by people subject to domestic violence restraining orders. Since that seems like a no-brainer, many people were dismayed when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit deemed that provision unconstitutional last year in United States v. Rahimi. But as anyone who reads the majority and concurring opinions in that case can see, there is a striking problem with 18 USC 922(g)(8): It disarms people even when there is little or no evidence that they pose a danger to others.

In an 8–1 decision today, the Supreme Court avoided that issue by noting that the man who challenged his prosecution under Section 922(g)(8), Zackey Rahimi, is a bad dude with an extensive history of violence, including violence against his girlfriend. As applied to people like Rahimi, Chief Justice John Roberts says in the majority opinion, the law is "consistent with this Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation"—the constitutional test that the Court established in the 2022 case New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen.

"When a restraining order contains a finding that an individual poses a credible threat to the physical safety of an intimate partner, that individual may—consistent with the Second Amendment—be banned from possessing firearms while the order is in effect," Roberts says. The decision does not address the question of whether it is consistent with the Second Amendment to disarm someone without such a judicial finding.

Noting that Rahimi raised a facial challenge, Roberts faults the 5th Circuit for focusing on "hypothetical scenarios where Section 922(g)(8) might raise constitutional concerns" instead of "consider[ing] the circumstances in which Section 922(g)(8) was most likely to be constitutional." That error, he says, "left the panel slaying a straw man."

As 5th Circuit Judge James Ho emphasized in his Rahimi concurrence, that "straw man" is not merely hypothetical. The "constitutional concerns" to which Roberts alludes derive from the statute's loose requirements for court orders that trigger the gun ban. Under Section 922(g)(8), a restraining order must include at least one of two elements, one of which sweeps broadly enough to encompass individuals with no history of violence or threats.

The first, optional element—a judicial finding that the respondent "represents a credible threat to the physical safety" of his "intimate partner" or that person's child—provides some assurance that the order addresses a real danger, especially since the law requires a hearing in which the respondent has "an opportunity to participate." As Roberts notes, the order against Rahimi included such a finding. But the second, alternative criterion—that the order "by its terms explicitly prohibits the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against such intimate partner or child that would reasonably be expected to cause bodily injury"—can be met by the boilerplate language of orders that are routinely granted in divorce cases, whether or not there is good reason to believe the respondent is apt to assault anyone.

In his Rahimi concurrence, Ho noted that protective orders are "often misused as a tactical device in divorce proceedings" and "are granted to virtually all who apply." They are "a tempting target for abuse," he said, and in some cases have been used to disarm the victims of domestic violence, leaving them "in greater danger than before."

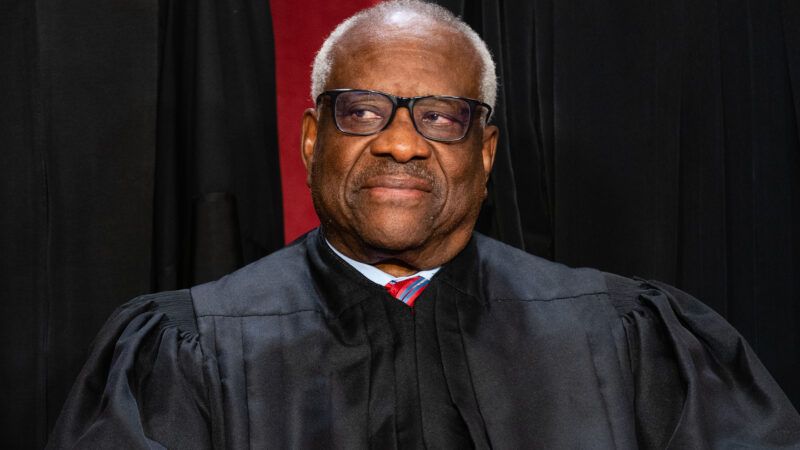

In the lone dissent from today's decision, Justice Clarence Thomas likewise notes how easily someone can lose his right to arms under Section 922(g)(8). The provision "does not require a finding that a person has ever committed a crime of domestic violence," he writes. It "is not triggered by a criminal conviction or a person's criminal history." And it "does not distinguish contested orders from joint orders—for example, when parties voluntarily enter a no-contact agreement or when both parties seek a restraining order."

Furthermore, Thomas says, the law "strips an individual of his ability to possess firearms and ammunition without any due process," since "the ban is an automatic, uncontestable consequence of certain orders." The Cato Institute made the same basic point about due process in a brief supporting Rahimi's challenge.

Although a hearing is required for the restraining order itself, Thomas notes, "there is no hearing or opportunity to be heard on the statute's applicability, and a court need not decide whether a person should be disarmed under §922(g)(8)." He also points out that the penalties for violating the provision are severe: up to 15 years in prison, plus permanent loss of gun rights based on the felony conviction.

Roberts, who criticizes the 5th Circuit for requiring a "historical twin" rather than a "historical analogue" under the Bruen test, sees precedent for Section 922(g)(8) in "surety" laws that required threatening people to post bonds, which they would forfeit if they became violent. But Thomas does not think those laws are "relevantly similar" to the provision that Rahimi violated.

"Surety laws were, in a nutshell, a fine on certain behavior," Thomas writes. "If a person threatened someone in his community, he was given the choice to either keep the peace or forfeit a sum of money. Surety laws thus shared the same justification as §922(g)(8), but they imposed a far less onerous burden."

In particular, Thomas says, "a surety demand did not alter an individual's right to keep and bear arms. After providing sureties, a person kept possession of all his firearms; could purchase additional firearms; and could carry firearms in public and private. Even if he breached the peace, the only penalty was that he and his sureties had to pay a sum of money. To disarm him, the Government would have to take some other action, such as imprisoning him for a crime." Thomas thinks the government "has not shown that §922(g)(8)'s more severe approach is consistent with our historical tradition of firearm regulation."

Roberts, by contrast, says a prosecution under Section 922(g)(8) can be consistent with that tradition, at least when a judge concludes that someone "poses a credible threat to the physical safety of an intimate partner." The constitutionality of applying Section 922(g)(8) in cases where there was no such finding remains uncertain. Some Second Amendment scholars, such as the Independence Institute's David Kopel, argue that the provision would be constitutional if it were amended to require a finding of dangerousness.

The Court did clarify an important point in a way that could bode well for other challenges to the broad categories of "prohibited persons" who are not allowed to possess firearms, such as cannabis consumers and other illegal drug users. The majority rejected the Biden administration's position that only "responsible" people qualify for Second Amendment rights.

"We reject the Government's contention that Rahimi may be disarmed simply because he is not 'responsible,'" Roberts writes. "'Responsible' is a vague term. It is unclear what such a rule would entail. Nor does such a line derive from our case law."

In Bruen and in District of Columbia v. Heller, the 2008 case in which the Court first explicitly recognized that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to armed self-defense, Roberts notes, "we used the term 'responsible' to describe the class of ordinary citizens who undoubtedly enjoy the Second Amendment right….But those decisions did not define the term and said nothing about the status of citizens who were not 'responsible.' The question was simply not presented."