Illinois Won't Let Him Do His Job Filing Paperwork—Unless He Gets a Private Detective License

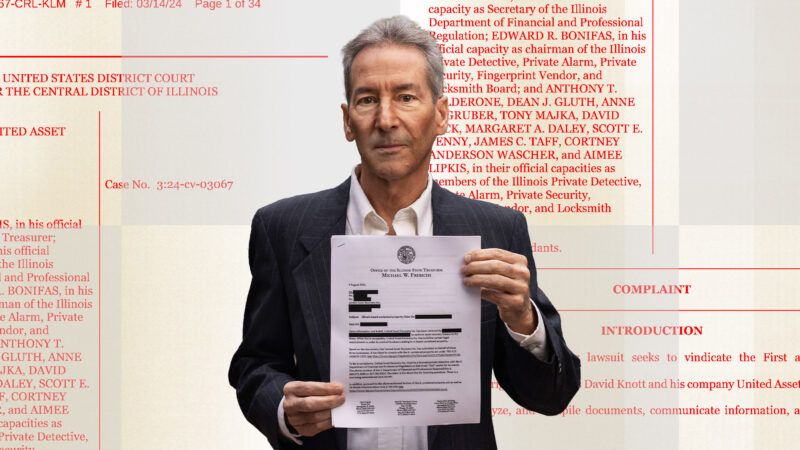

David Knott helps clients retrieve unclaimed property from the government. The state has made it considerably harder for him to do that.

Should you need to display competency in crime scene evaluation, interviewing and interrogation techniques, electronic surveillance, and firearms in order to file paperwork with the government?

Common sense answers that question. But common sense, unfortunately, doesn't always drive policy, so it will instead be up to a federal court to consider that query as a part of a federal lawsuit at the nexus of occupational licensing and free speech.

David Knott is the paperwork filer in question. And there is quite a bit of paperwork for him to file. Knott's company, United Asset Recovery Inc., helps clients reclaim lost personal property held by the government: Across the country, states take possession of lost assets—uncashed checks, abandoned bank accounts, etc.—but they are required to return them if the owner petitions the state and successfully proves that he or she is the rightful owner.

If is the operative word here. Many people don't realize the government is holding their property, or they don't know how to get it back, which is why companies like Knott's exist. Paid by commission, he checks government databases listing unclaimed property, contacts the owners, and offers his services in filing the necessary paperwork to retrieve their property.

But in 2021, the state of Illinois told Knott he was no longer permitted to do so unless he obtained a private detective's license, which would require he apprentice for three years with an investigator, a licensed attorney, a corporation with 100 or more employees, the armed forces, or a law enforcement agency. This is despite that he does not, in fact, have any interest in being a private investigator. He would also have to prove he is adept at the areas mentioned above—crime scene investigation, interrogation, surveillance, and firearms—despite, again, that he has no intention of employing any of those skills.

Should Knott ignore the government's directive, he would face criminal prosecution—a misdemeanor for the first offense, a felony for any subsequent one—and a $10,000 fine per infraction.

His lawsuit alleges that framework is unconstitutional. Illinois law bars Knott and his company "from reading, analyzing, communicating, or compiling information and documents concerning their clients' or potential clients' unclaimed property in exchange for an industry-standard contingent commission," reads his complaint, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of Illinois. "That is a content-based restriction on speech; the law applies to Plaintiffs only because of the type of information and documents—the communicative content—that they want to read, analyze, communicate, and compile." Also at stake is the First Amendment right to petition the government, which would seem exceedingly relevant when considering that property owners themselves do not need a private detective license to petition the state for their property back. So why should Knott?

The suit further alleges that the Illinois government is violating Knott's 14th Amendment right to pursue an occupation without irrational government intrusion. "Plaintiffs' occupation is so different from conventional private detective work that any governmental interest in regulating private detectives is not implicated," notes his complaint. "None of the experience required to obtain a private detective license has any meaningful connection to Plaintiffs' work finding and recovering unclaimed property."

When considering that last point—that it essentially takes Simone Biles–level mental gymnastics to connect Knott's work to the detective license—it's worth asking why the state requires this at all. Knott's suit offers an answer: "Illinois has a clear incentive to impose irrational and unnecessary barriers like the license requirement: The fewer people recover their property, the more money the state has to shore up its budget." (The state currently has over $5 billion in unclaimed property.)

That theory isn't just applicable to an obscure debate in Illinois. As I've previously written, many governments across the U.S. have made it laughably difficult for people to get their property back after it is seized via civil forfeiture, the practice that allows the state to take people's money or property if they are merely suspected of a crime. Innocent property owners may have to navigate a labyrinthine obstacle course before they can get their stuff back—if they manage to make it to the end—as years go by before they're even permitted a hearing. That those hurdles discourage people from fighting for their property back is not an oopsie. It's a feature, not a bug.

For his part, Knott will soon find out if such a feature can withstand constitutional scrutiny when it paralyzes his ability to do something very basic: file paperwork with the government.

Show Comments (16)