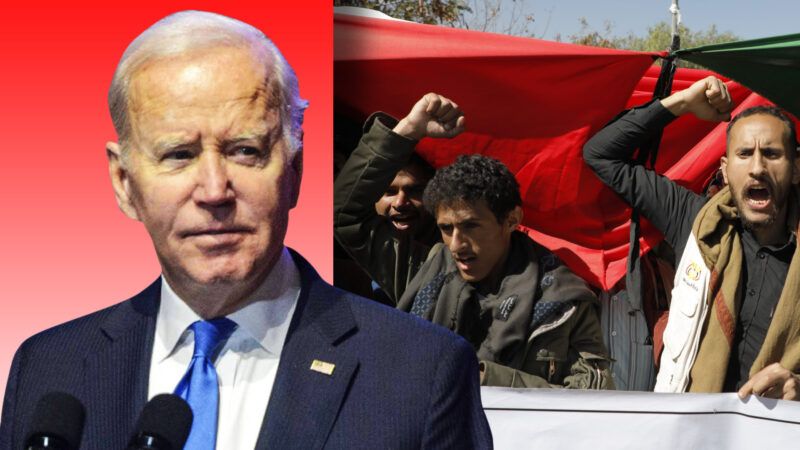

The War on Terror Zombie Army Has Assembled

All of the unfinished U.S. conflicts in the Middle East are coming together into one big crisis for Biden.

President Joe Biden announced U.S. airstrikes on the Houthi movement, one of two competing factions claiming to be Yemen's government, on Thursday. The attacks came after Houthi drone and missile attacks on trade routes in the Red Sea, which Houthi leadership said was meant to pressure Israel to lift its siege on Gaza. Several members of Congress from both parties said that Biden had no constitutional authority to attack. Biden justified the strikes in terms of self-defense.

It was a new escalation, and it wasn't. The United States has been involved in Yemen for years, striking Al Qaeda and supporting a Saudi-led coalition against the Houthis. But Thursday was the first open combat between the U.S. military and Houthi forces, except for a limited incident in 2016. It was also the first airstrike in Yemen by anyone in nearly two years. Saudi Arabia had accepted a truce and peace talks in early 2022, partly because of U.S. pressure.

The Intercept also reported on Friday that special U.S. Air Force intelligence teams, whose job is to share targeting data, had been ordered to Israel. Although the Biden administration has claimed that it is only sharing intelligence with Israel for hostage rescue missions, the arrival of the targeting teams suggests that Washington is playing a much more active role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict than ever before.

Meanwhile, the Iraqi government is asking the U.S. military to leave Iraq after a U.S. drone strike killed an Iraqi militia commander. (Behind the scenes, Biden administration officials seem confident that the notion of expelling Americans from Iraq is empty talk.) Although U.S. forces have been battling pro-Iran militias in Iraq for decades now, there had been a monthslong truce in place, which Iraqi militias decided to break after war erupted in Gaza.

All of the ghosts—or perhaps zombies—of U.S. foreign policy for the past 30 years seem to be assembling into one big war. Since the Obama administration, Washington has promised to pull U.S. forces out of the Middle East, while quietly dabbling in proxy wars all over the region. That arrangement turned out to be neither stable nor sustainable. Right under everyone's noses, and without permission from Congress, the United States has gone from proxy warfare back to direct combat in the Middle East.

The immediate cause of the crisis was unexpected: the mass Hamas-led killing and kidnapping of Israelis last October and the Israeli invasion of Gaza in response. But the underlying dynamics were there for everyone to see. American leaders believed that they could impose an unpopular order on the Middle East without putting in much effort and freeze the Middle East's conflicts on Washington's terms. And like an overconfident character in a horror movie, the Biden administration accidentally foreshadowed the bloody events to come.

"The Middle East region is quieter today than it has been in two decades now," National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said a week before the war. "Now challenges remain—Iran's nuclear weapons program, the tensions between Israelis and Palestinians—but the amount of time that I have to spend on crisis and conflict in the Middle East today compared to any of my predecessors going back to 9/11 is significantly reduced."

Those "challenges" have now combined into the worst Middle Eastern crisis in decades.

Sullivan had borrowed his playbook, the Abraham Accords, from the Trump administration. The idea was to unite Israel and the oil-rich Arab monarchies through their common enmity with Iran. Security ties would lead to economic cooperation and cultural normalization, while the Iranian government would collapse on its own under the pressure. U.S. military forces could underwrite the whole thing without getting involved directly.

The Iranian nuclear program indeed seemed to be the biggest threat. Although the CIA does not believe Iran is currently building an atomic weapon, its nuclear infrastructure could be used for that purpose. Former President Barack Obama had believed that, unless a U.S.-Iranian deal was struck, he would have to choose between bombing Iran or accepting an Iranian bomb. The Trump administration offered a different option: Exert pressure that "expands the space" for an uprising against the Iranian government. That seemed to work. Halfway into the Biden era, Iran faced its most intense unrest since the 1979 revolution.

One wrinkle remained: several million Palestinians, living under various degrees of Israeli control, with neither a country of their own nor legal status in any other country. The hopeful days of the "two-state solution," negotiations to create a State of Palestine living peacefully alongside the State of Israel, had gone by. A growing chunk of Palestinian society supported armed rebellion, and a growing chunk of Israeli society supported "population transfer," a euphemism for ethnic cleansing.

The Trump administration was unbothered. "The biggest threat that our allies and partners in the region face is not the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. It's Iran. You've got to start there," Trump administration official Brian Hook said in August 2020. As was the Biden administration. Current Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in January 2021 that "it's hard to see near-term prospects for moving forward" on the issue.

Perhaps the United States alone could have solved the conflict; perhaps no one could have. Either way, Washington had tied itself to the outcome. Israel continued to receive U.S. military aid in greater amounts and with fewer conditions than any other country. And the Abraham Accords made Israel a key part of the entire Middle East's security architecture.

Meanwhile, Tehran was licking its wounds. Although the Islamic Republic of Iran is internationally isolated and domestically losing control, it has many cards left to play. Iranian leaders can still count on a large arsenal of missiles and drones and an array of pro-Iran guerrilla forces across the region. (The Houthis are one such group.) Saudi Arabia, once an advocate for bombing Iran, decided to cut its losses and accept a diplomatic deal with Iran last year.

The stage was set, then, for the October war to spread all over the region. The Abraham Accords were exposed as both fragile and unpopular in the Arab world, especially after Israeli leaders began to talk about expelling Palestinians from Gaza en masse. Iran had a golden opportunity to escalate on its terms. Hezbollah, the pro-Iran party in Lebanon, immediately began firing on Israeli territory. Biden sent two aircraft carriers to the region to deter any further escalation against Israel, while also talking Israel out of a preemptive war on Lebanon.

Iraqi militias broke their truce with Americans the following week. The U.S. bases originally set up to overthrow Saddam Hussein and repurposed for the war against the Islamic State were now redoubts against Iran's Iraqi supporters. Like the Obama and Trump administrations before it, the Biden administration cited the original Iraq War authorization to justify its newest battle.

Then the Houthis began to menace international commerce. Houthi spokesman Yahya Sare'e claimed that Israeli shipping was a "legitimate target" until the siege of Gaza was lifted. Echoing the logic of liberal American hawks, he claimed that Yemen had a responsibility to protect Palestinian civilians. But the Houthi attacks also struck non-Israeli ships and drove international shipping companies out of the Red Sea, which normally carries around 10 percent of global trade.

As it turned out, the problem wouldn't take care of itself. Despite the Abraham Accords, no Arab state except Bahrain was willing to intervene against the Houthis on behalf of Israeli shipping. (Saudi Arabia also seemed more concerned with maintaining its own truce.) Biden decided to cobble together his own fleet to fend off the Houthi assaults.

There is another small wrinkle: None of these fights have any mandate from the American people. Congress last authorized military action against Iraq in 2002. It has never passed a law allowing the president to threaten Lebanon out of shelling Israel, nor one allowing the Navy to bomb Yemen out of threatening cargo ships. The Biden administration has tried to keep its support for Israel, including a U.S. military base on Israeli soil, as secretive as possible.

For all the sound and fury about college campuses, there has been no real national conversation on U.S. involvement in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or its regional spillover. Before the October attacks, Washington seemed confident that it could steer events from a distance. Now that U.S. forces are directly involved, American leaders are pretending that it was a sad inevitability, that their hands were forced.

Or perhaps they're not pretending. Earlier this week, Blinken was in Saudi Arabia, trying to convince reporters that the crown prince was still interested in joining the Abraham Accords. Like zombies, they shuffle off into the distance, not really understanding where they came from or where they're going. Unfortunately, they're dragging the rest of us behind them.

Show Comments (145)