'The Science' Suffers from Self-Inflicted Political Wounds

A separation of science and politics might be called for.

Once upon a time, science evoked enthusiasm. Yes, cinematic mad scientists went overboard with body parts and lightning, but real-life researchers brought us innovations, insights, and improved standards of living. But, like many institutions, science got political and cult-y. Thin-skinned narcissists with government jobs hijacked the systematic pursuit of knowledge and rebranded it as an unassailable body of Truth with a capital T. They cast out as heretics well-informed critics who interpreted evidence differently. In the process, they lost the trust of a public which saw insights replaced by bossy ideologues.

You are reading The Rattler from J.D. Tuccille and Reason. Get more of J.D.'s commentary on government overreach and threats to everyday liberty.

Plunging Confidence in Science

"A new Pew Research Center survey finds the share of Americans who say science has had a mostly positive effect on society has fallen and there's been a continued decline in public trust in scientists," the organization reported last week. "Overall, 57% of Americans say science has had a mostly positive effect on society. This share is down 8 percentage points since November 2021 and down 16 points since before the start of the coronavirus outbreak."

A full third of Americans say science is a wash, equally positive and negative. Eight percent say it's mostly negative. The plunge in support since the appearance of COVID-19 is no coincidence; that's when some scientists, especially those in official positions, began wielding "science" as a shield against debate and a tool for control.

It seemed reasonable in 2020 to heed widespread calls to "follow the science." With the outbreak of the pandemic why not let people versed in studying and dealing with disease set the tone? Pretty quickly, though, politicians and public health officials began justifying drastic and controversial measures such as lockdowns, mask mandates, and school closures as dictated by "the science."

"The phrase became associated with safetyism and overcaution, like people would use it sarcastically when they saw someone running through a field wearing an N95 mask," Faye Flam, a science journalist who launched the "Follow the Science" podcast and came to regret her choice of name, told The Washington Post last year. "So much is mixed up with science — risk and values and politics — the phrase can come off as sanctimonious, and the danger is that it says, 'These are the facts,' when it should say, 'This is the situation as we understand it now and that understanding will keep changing.'"

"Sanctimonious" is a good description for officials who wield "science" to shield against criticism.

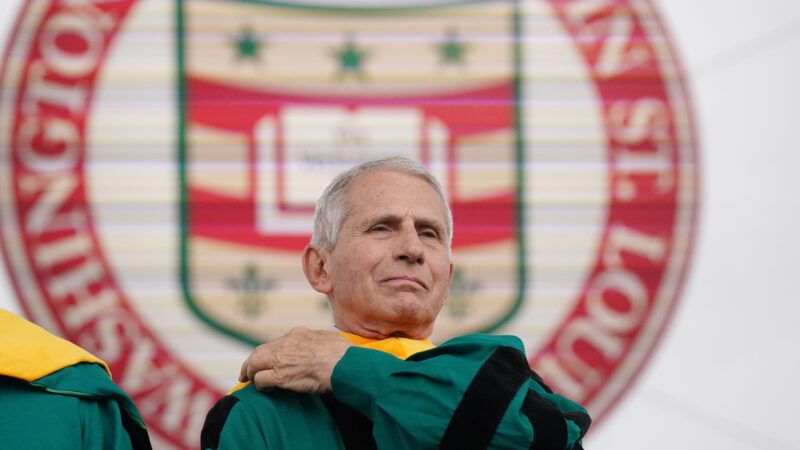

"It's easy to criticize, but they're really criticizing science because I represent science," Dr. Anthony Fauci, former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and then medical advisor to President Biden, told CBS News in 2021. "If you damage science, you are doing something very detrimental to society long after I leave."

Fauci and company "represent science," they claim, but medical experts who disagree with their takes on COVID-19, its source in a lab leak or nature, and proper pandemic responses, do not.

Heretics and "The Science"

After Elon Musk acquired Twitter (now X), he released internal documents to the press revealing "concerted efforts by various federal agencies—including the FBI, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and even the White House—to convince Twitter to restrict speech," noted Reason's Robby Soave. "According to a trove of confidential documents obtained by Reason, health advisers at the CDC had significant input on pandemic-era social media policies at Facebook as well."

Among those targeted for suppression were Jay Bhattacharya, a Stanford University professor of health policy, and Martin Kulldorff, a Harvard University professor of medicine.

"On Friday, at long last, the Fifth Circuit Court ruled that we were not imagining it—that the Biden administration did indeed strong-arm social media companies into doing its bidding," Bhattacharya wrote in September after a court victory (over suppressed speech reaching beyond the realm of public health policy). "The court found that the Biden White House, the CDC, the U.S. Surgeon General's office, and the FBI 'engaged in a years-long pressure campaign [on social media outlets] designed to ensure that the censorship aligned with the government's preferred viewpoints.'"

The rot went further than officialdom, reaching into public-facing institutions.

"High-profile political endorsements by scientific publications have become common in recent years, raising concerns about backlash against the endorsing organizations and scientific expertise," Stanford University's Floyd Jiuyun Zhang wrote earlier this year of a study of the effects of pro-Biden messaging in Nature. "Results suggest that political endorsement by scientific journals can undermine and polarize public confidence in the endorsing journals and the scientific community."

Overt politicization, after court cases, following the publication of company documents, revealed officials and experts purporting to "follow the science" while actually indulging their own preferences and suppressing dissent.

A Partisan Divide Becomes Shared Doubt

Up to this point, the eroding credibility of science was largely a partisan matter. Democrats "followed the science" to restrictive public-health policies. Republicans, who generally favored a lighter public-health touch, doubted that public health officials wrapping themselves in science as if it was priestly garb could be trusted. Surveys showed the predictable outcome.

"Confidence in science has grown among Democrats since 2018, but decreased among Republicans," the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research reported in January 2022.

A year later, after the social media files and court cases, the same survey showed that "confidence among Democrats was back to its pre-pandemic level after a short-term surge of trust during the pandemic." Democrats expressing a "great deal" of confidence fell from 64 to 53 percent (Republican confidence plummeted from 34 to 22 percent). That result is echoed elsewhere.

"The share of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents with a great deal of confidence in scientists – which initially rose in the pandemic's first year – now stands at 37%, down from a high of 55% in November 2020," Pew noted last week. (Republicans expressing similar confidence fell from a high of 27 percent in April 2020 to 11 percent.)

Democrats remain more likely than Republicans to be confident in scientists to act in the public's best interests, and majorities of partisans of both parties as well as independents retain at least a fair amount of confidence in scientists. But an enormous amount of good will has been lost.

Last month, the Senate confirmed Monica Bertagnolli as the new director of the National Institutes of Health with a mandate to "rebuild trust in science." Jettisoning politics and refraining from using science to push policies and personal preferences would be a good start.

Show Comments (241)