Rachel Maddow's Prequel Is a Deceptively Framed History of the Radical Right

The book blames foreign subversives for ideas long rooted in American life.

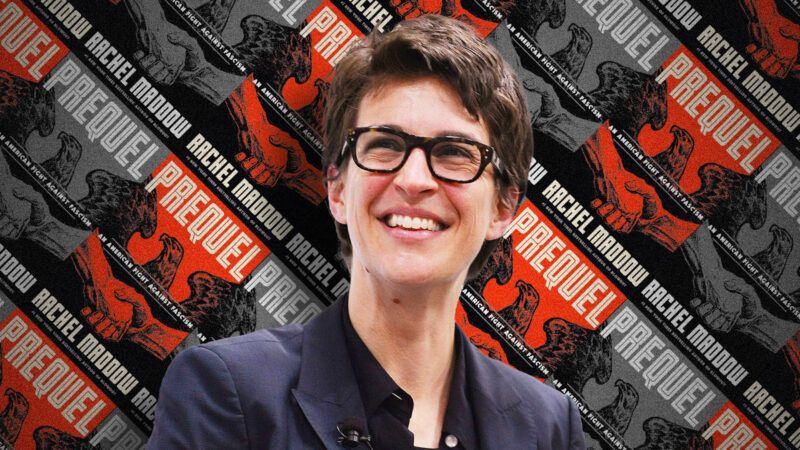

Prequel: An American Fight Against Fascism, by Rachel Maddow, Crown, 416 pages, $32

"American democracy itself was under attack from enemies within and without," Rachel Maddow writes in Prequel: An American Fight Against Fascism. If you're not sure whether she is speaking of the past or the present, that's because she wants to conflate the two.

Prequel is a deeply flawed and deceptively framed history of right-wing radicalism in the United States on the eve of American entry into World War II. Maddow's treatment of this well-worn topic draws principally from primary sources generated from the protagonists of her story, a collection of private spies and anti-fascist activists, as well as contemporary press reporting, sundry government documents, and a narrow base of secondary sources, one that noticeably omits prominent works in the field. Deficiencies in her sources, methods, and analyses make for a book that recapitulates past passions at the expense of sober reflection and reality.

Maddow opens with her strongest case study, covering the German-born Nazi agent George Sylvester Viereck, who tried to push Americans toward neutrality by using personal connections with Congress to spread noninterventionist literature. She then switches focus to her weakest case study, that of populist Democratic governor and senator Huey "Kingfish" Long and his influence on the Nazi sympathizers Philip Johnson and Gerald L.K. Smith. Maddow does not clarify why Long, who died in 1935, is discussed here. But her tone and source selection imply that she agrees with the Kingfish's contemporary critics that his populism and demagoguery made him a proto-fascist and a political gateway drug for more radical figures, like Johnson and Smith.

Maddow then abruptly changes focus to the dark history of American segregation and its influence on Nazi racial science, following the German lawyer Heinrich Krieger's travels through the American South. Then she circles back to more-prominent characters, such as the American fascist Lawrence Dennis, the antisemitic preacher Charles Coughlin, and the abstruse spiritualist (and leader of the fascist Silver Shirts) William Dudley Pelley, among others.

The book's first half is occasionally productive. The chapter on Pelley does a good job of exploring the roots of his ideology: his conflation of anti-communism with antisemitism, his eclectic spiritualism, his millenarian Christianity. And the chapter on American race law is a haunting look at how American legislatures maintained racial hierarchy and what the Nazis learned from their practices.

But what narrative value she creates is relinquished by her analytical leaps, which conflate fascism with phenomena that were already well-grounded in American life well before the 1920s. And Maddow never directly states the size and scope of the groups she covers, such as the German American Bund and the Silver Shirts; instead we get such vague phrases as "many," "a lot," and "an insane number." This makes it easier to confuse the breadth of Maddow's cast of characters for the depth of their influence. (According to historian Francis MacDonnell's Insidious Foes, the German American Bund never attracted more than 25,000 members and the Silver Shirts maxed out at 15,000.)

The book's meandering journey narrows in later chapters, as Maddow argues that German propaganda had a pervasive influence on "isolationist" congressmen. She presents the propagandists' efforts as far more effective than they were, giving the impression that they were the root of Americans' general desire to stay out of World War II. She pays only lip service to the deeper roots of "isolationism," with a mere passing reference to the fallout from World War I. She does not mention the post-WWI revelations of Allied and American propaganda, the widespread alarm at the armaments industry's intimate relationship with the government, or the Great War's domestic abuses of civil liberties. (When Sen. Ernest Lundeen (R–Minn.) denounces a draft bill as "nothing short of slavery," she dismisses him as "shrill.") Instead, she writes as though the desire to remain neutral simply stemmed from abroad, stripping noninterventionism of its historical context and arguing that the "threads of isolationism, antisemitism, and fascism were becoming an ominously tight weave."

To make her case, Maddow retells a well-worn story about Viereck's use of the congressional frank, a taxpayer-funded mailing service, to distribute what Maddow calls "pro-German mailings." In fact, it was predominately literature that advocated neutrality. As historian Douglas M. Charles argued in J. Edgar Hoover and the Anti-interventionists, "All Viereck managed to accomplish was a wider distribution of anti-interventionist literature that, in any event, did not lead Americans to reassess their views on the Allies."

Her book culminates in the 1944 sedition trial, in which the United States federal government charged a heterogeneous and largely unaffiliated assortment of 30 defendants, which included far-right figures like George Sylvester Viereck, Lawrence Dennis, and William Dudley Pelley, for sedition under the 1940 Smith Act. She presents the episode as a missed opportunity to uproot homegrown fascism. In fact, the Justice Department filed its flimsy charges on politically motivated grounds—a clear threat to constitutionally protected speech and association, no matter how unsympathetic the defendants could be.

Throughout Prequel, Maddow displays a systemically uncritical use of her source material, frequently presenting the self-gratifying hyperbole of fascist propagandists and the motivated reasoning of anti-fascist reporters as gospel.

Whether she knows it or not, Maddow is dredging up a thesis from the past, written in the wake of World War II when passions were high and perspectives blinkered. This view does have some academic adherents, and she cites their work: Bradley W. Hart's Hitler's American Friends, James Q. Whitman's Hitler's American Model, Sarah Churchwell's Behold, America, Steven J. Ross's Hitler in Los Angeles, and others. But she drives her thesis beyond the confines of her evidence in a manner that these scholars do not. Hart, for example, hedges where Maddow does not, acknowledging that the "United States was not at risk of an imminent fascist takeover in the late 1930s" when he argues that there was "fertile terrain in which dictatorship might be able to take root." Yet Maddow leaves the impression that there was a risk of an imminent fascist takeover in the 1930s, with German propaganda fertilizing that fertile terrain.

Meanwhile, there is a sizeable body of work that challenges Maddow's thesis and that of her source material. Such works include established scholarship such as Leo Ribuffo's The Old Christian Right, Deborah Lipstadt's Beyond Belief, and Bruce Kuklick's recent Fascism Comes to America, to name a few. While these works do not downplay the pernicious ideologies of the far right nor their presence in American life, they do not sensationalize or dehistoricize them nor assign them more influence than they deserve. Lipstadt, who has devoted much of her career to combating the radical right's penchant for Holocaust denial, dedicated an entire chapter of Beyond Belief to challenging American anxieties about a Nazi "fifth column"—the very fears that Maddow is trying to resurrect. While Nazi Germany did have spies and propagandists in the U.S., Lipstadt cautioned that "they never constituted a network with the scope and power the press attributed them."

In Insidious Foes, MacDonnell argues that while odious and illiberal, right-wing extremists "never posed any real danger to the republic"; instead, a media echo chamber constructed the perception of a vast and powerful far right. He also makes a good case that Germany's propaganda effort was "spectacularly unsuccessful" and ultimately did more damage to the noninterventionist cause than it aided it. Ribuffo's classic The Old Christian Right (a work that Maddow mentions in her author's note but does not cite) similarly argued that the fear of these groups was a "brown scare" that often "exaggerated both [the far right's] power and its Axis connections."

How does Maddow square her findings with those of these earlier works? We do not know, because she does not tell us.

In closing the book, Maddow invites the reader to take inspiration from the work of Americans who sought to stop homegrown fascists by "any means at hand," assessing their legacies as worth remembering and emulating. Yet Maddow omits the pernicious legacy that followed from using "any means at hand" and violating the very norms her heroes sought to protect. They created the destructive and restrictive myth of isolationism, which held that it was an absence of American power from the world's stage that directly led to the rise of fascism abroad. They actively colluded with a foreign power—Great Britain—to interfere in American elections and manipulate American media. And they helped stoke the panic that led to Japanese internment and spurred the growth of the domestic security state. The latter, ironically, soon boomeranged against the left.

Those legacies are also worth remembering if we are to preserve liberty from an ever-present threat—not from enemies within our ranks or outside our walls, but within ourselves.

Show Comments (117)