How the Media Got the Vinyl Chloride Risk All Wrong

The Ohio train accident was frightening enough. Spreading inaccurate information won’t help the citizens of East Palestine.

The residents of East Palestine, Ohio, have more than enough to worry about. A train wreck with black fumes of burning chemicals pouring from a tank is frightening enough. The absolute last thing they need is the news media spreading even scarier—but inaccurate—information about the accident.

Yet for weeks, that is precisely what's been going on.

Vinyl chloride, a chemical long used to make PVC plastics, is being portrayed as something more suitable for capital punishment than for a routine manufacturing process in a factory. Ohioans, like the rest of the country, are being bombarded by horrifying claims about its health risks, most of which have been just plain wrong.

There is, in fact, strong evidence that vinyl chloride not only is not deadly but is, in fact, considerably less toxic than many common, everyday drugs and chemicals. Likewise, its cancer risks have also been wildly overstated. It is easy to call a chemical a carcinogen, but in the absence of context, dose, and length of exposure, this term means little.

Fortunately, there is a longstanding, highly regarded organization that provides information on the health risks of individual chemicals. The National Fire Prevention Association (NFPA) describes itself as "a global self-funded nonprofit organization, established in 1896, devoted to eliminating death, injury, property and economic loss due to fire, electrical and related hazards." The group maintains a database of more than 3,000 chemicals—a critical tool for first responders or other workers who must deal with the aftermath of a chemical spill or fire. Here we can begin to understand the real risks of vinyl chloride.

NFPA uses color-coded "safety diamonds" to provide easily read information about chemicals that firefighters may encounter. They quickly cover a chemical's health hazards, flammability, and stability (that is, whether it can spontaneously explode), along with any special warnings—for example, when exposure to water must be avoided.

NFPA classifies health hazards on a scale of 0 to 4, where 0 indicates little or no hazard and 4 is reserved for deadly chemicals that can kill even with short exposure. Vinyl chloride has a 2 rating—a "moderate" hazard, described as posing a "temporary or minor, reversible injury [that may be] harmful if swallowed, inhaled, or absorbed through the skin."

To put this in perspective, both alcohol and chloroform—the latter was used for general anesthesia for 125 years—are also rated 2. Both alcohol and chloroform are also known carcinogens.

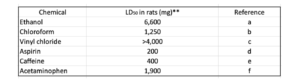

The disconnect between the data and the coverage becomes even more apparent when data from animal models of toxicity are considered. One common measure of toxicity is the LD50, which stands for "lethal dose 50 percent"—the amount of material given at once (usually orally) that kills half of the test animals. Although these data cannot be quantitatively applied to human beings, LD50 values are useful for identifying which chemicals are very toxic (and which are very safe). If vinyl chloride was highly toxic, the test would indicate it.

In rats, ethanol and vinyl chloride are both non-toxic; it takes a large dose to kill the animal. Both caffeine and aspirin are at least 10 times more toxic than vinyl chloride.

Ohio residents are being exposed primarily by inhalation, not oral consumption, which may reduce the relevance of LD50 values. But according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, vinyl chloride toxicity via inhalation is low in both rodents and people. It is not unreasonable to assume that the chemical would have been useful for general anesthesia when the science was in its infancy. Indeed, a 1947 study showed that it not only was efficacious in animals but was less toxic than chloroform, although the authors ultimately recommended against its use in general anesthesia because the therapeutic index—the difference between the effective and lethal dose—was too small.

The cancer risks, probably the scariest to most people, have also been badly exaggerated. But in a different way—duration of exposure.

Cancers do not result from single exposure to chemical carcinogens. It takes years for cigarette smokers to develop lung cancer. The chances of cancer developing many years later from a single or brief exposure, whether it be one cigarette, a pack, or even a carton, are infinitesimally small. The same holds true for vinyl chloride; it is an occupational carcinogen. Between its volatility and rapid metabolism, vinyl chloride does not accumulate in the human body.

Aside from the possibility of catastrophic explosion, there is one genuine scare from vinyl chloride: its combustion products.

When it burns—as it is still doing today—vinyl chloride is known to produce deadly phosgene gas (a WWI chemical weapon) and hydrogen chloride, a highly corrosive irritant. The latter is probably responsible for residents' symptoms and fish deaths, since fish are extremely sensitive to acidic water.

While it seems clear that hydrogen chloride exposure is real, the same cannot be said for phosgene. Had people near the accident been exposed to significant amounts of phosgene (and it doesn't take much), the picture would be very different. Intensive care units and morgues would be full. In the absence of severe illness and death, it can reasonably be assumed that phosgene has not been released in significant quantities

Finally, the threat from the accident could have been far worse had the train been carrying some of the highly toxic chemicals—far worse than vinyl chloride—that are routinely shipped around the country. But this is little comfort to East Palestine residents. They are still coping with a burning train containing at least five other chemicals. The last thing they need are sensationalized, inaccurate reports of a rather benign chemical in their midst.

Show Comments (83)