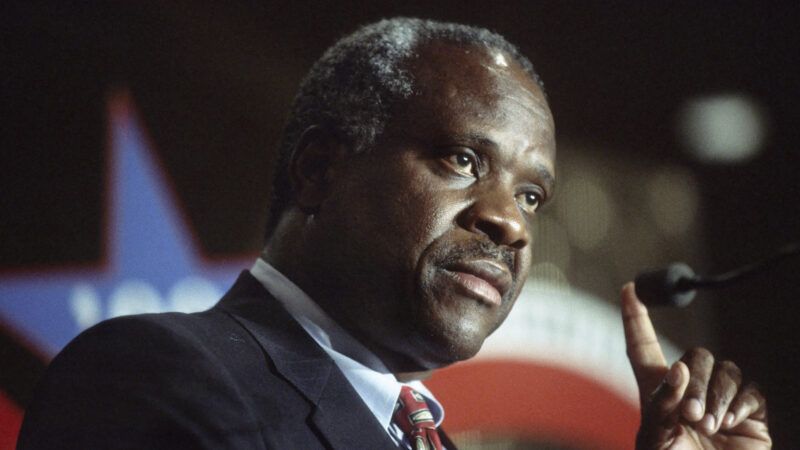

On Affirmative Action, Clarence Thomas Took a Page From Malcolm X

Understanding the jurisprudence of the conservative Supreme Court justice

Later this month, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in a pair of cases—Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina—which ask whether the use of race as a factor in determining college and university admissions violates the Constitution. One justice who will undoubtedly vote against affirmative action in those cases is Clarence Thomas, who has spent years calling for the practice to be overruled.

"When blacks take positions in the highest places of government, industry, or academia, it is an open question today whether their skin color played a part in their advancement," Thomas wrote in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), in which the Court upheld the University of Michigan's use of race in law school admissions. "The question itself is the stigma—because either racial discrimination did play a role, in which case the person may be deemed 'otherwise unqualified,' or it did not, in which case asking the question itself unfairly marks those blacks who would succeed without discrimination."

Similarly, in the affirmative action case Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (2013), Thomas maintained that, "although cloaked in good intentions, the University's racial tinkering harms the very people it claims to be helping." He argued that "all applicants must be treated equally under the law, and no benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify racial discrimination."

Thomas' critics sometimes misunderstand his stance in such cases, wrongly accusing him of believing that American racism is simply dead and gone. For instance, New York Times pundit Charles Blow probably spoke for many when he faulted Thomas for "being unable to acknowledge and articulate the basic fact that race was—and remains—a concern."

In fact, a closer look at Thomas' jurisprudence shows that race is one of his principal concerns, including in cases that are not obviously about race. Take Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), in which Thomas joined a majority of the Court in upholding the constitutionality of a school voucher program. "While the romanticized ideal of universal public education resonates with the cognoscenti who oppose vouchers, poor urban families just want the best education for their children," Thomas wrote. "If society cannot end racial discrimination, at least it can arm minorities with the education to defend themselves from some of discrimination's effects."

If society cannot end racial discrimination. Those are not the words of someone who doubts the persistence of racism. But they are also not the words of a modern liberal, who would probably say that benevolent government programs can and should be trusted to solve the problem. If anything, Thomas' words are closer to the views of the late Malcolm X, who, like Thomas, preached black self-reliance while distrusting even the most well-intentioned white liberals of his day.

And that resemblance is no wonder, since Malcolm X was one of Thomas' early heroes. "I've been very partial to Malcolm X, particularly his self-help teachings," Thomas told Reason in 1987. "I have virtually all of the recorded speeches of Malcolm X." In his 2007 autobiography, My Grandfather's Son, Thomas wrote that while he "never went along with the militant [racial] separatism" preached by Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam, "I admired their determination to 'do for self, brother,' as well as their discipline and dignity."

That admiration is still present in aspects of Thomas' jurisprudence today. Whether you agree with his take on affirmative action or not, Thomas' views can only be fully understood once you recognize this underappreciated influence on his thinking.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I like Clarence Thomas.

He's not perfect, but he's probably the second best justice on the court.

Great article, Mike. I appreciate your work, I'm now creating over $35400 dollars each month simply by doing a simple job online! I do know You currently making a lot of (aos-06) greenbacks online from $28000 dollars, its simple online operating jobs

Just open the link——————–>>> https://smart.online100.workers.dev/

Who's first?

Probably on balance, the best jurist on the court today. I've always said, be careful about picking a favorite because at some point, they will disappoint you. Thomas certainly has... in the case of a strip search of a high school girl over drugs-- was one of those times if I recall. His deference to law enforcement is not a high point for him. But in general he's probably the best we have.

Since he’s doing good, and giving a public platform to a perspective different from what’s “expected” from a black man, he’s a key target of the establishment he’s trying to enter.

I don’t know how the new Justice Jackson will be, but the people who appointed her expect her to stay on the woke side and adopt the “prog harder” school of lefty jurisprudence.

Perhaps she can "evolve" in office, only this time in a good direction?

Perhaps she can “evolve” in office, only this time in a good direction?

That seems overly optimistic. The entire power structure pushes left, and she knows her history will be written by the craziest leftist in the academy. It takes a Herculean commitment to ideological independence to resist this pressure, and she's never shown any such commitment at all. Further if she had she would never have been a Dem nominee.

Judges almost always move to the left once appointed.

She will be a full on Stalinist in short order.

She will have to recuse herself from every case involving a "Woman" 'cos she has sworn she doesn't even know what that is in her Congressional Testimony.

Don't think for one moment that Jackson will turn. She's just like Sotomayor or Kagan.

I think so. I always emphasize the importance of reasoning over conclusions. This is particularly true with jurists, and absolutely true with Supreme Court members.

I might disagree with things now and again, particularly in criminal cases as you said, but he's a truly consistent person who has described a distinct and consistent worldview over decades. He's par excellence.

We have other good members though as well. Big fan of Gorsuch from what I've seen so far.

He's pretty good. I miss having him and Scalia together.

...me too.

"although cloaked in good intentions, the University's racial tinkering harms the very people it claims to be helping." He argued that "all applicants must be treated equally under the law, and no benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify racial discrimination."

Juxtaposed with:

"...a modern liberal, who would probably say that benevolent government programs can and should be trusted to solve the problem."

I ask, who is the real beneficiary of such programs?

…a modern liberal, who would probably say that benevolent government programs can and should be trusted to solve the problem.”

The assumption is that blacks can't solve the problem themselves. There you see the racism inherent in the system and the legacy of white supremacy as it lives on in the minds of white liberals. White liberals are the biggest white supremacists left on earth.

It's their raison d'etre. Part of being a good, thoughtful, and high minded person. Unlike those horrid and terribly bad deplorables, who live in places Hillary Clinton does not like.

Apply Public Choice theory. AA/quota programs benefit those who run them. It's jobs for the /b/o/y/s/ humans.

If anyone overlooks his discussion of racial issues on the Court, and his concern for other black people, it's a case of preferring narrative over facts.

The narrative says he's an Uncle Tom who does the bidding of the white power structure, *therefore* he can't have any special concern about black people.

The power of the narrative is such that it seems sensible people need to point out the obvious.

GOOGF

Does this make Malcolm X an Uncle Tom now too? I like to keep my books straight.

Within the constraints of a Loony-Tunes organization, he was able to draw some conclusions discomfiting to the establishment.

He also made the mistake of leaving the Loony-Tunes organization and incurring its wrath.

I like to keep my books straight.

Fucking racist.

And homophobic... He said straight he obviously hates LGBTQIAZXRYB (I'm not sure how many letters I need to add today, anyone got the new rules, I wouldn't want to leave anyone out).

LOMGWTFBBQ?+

definitely missing a "2" I've seen "2" in there recently

I think there are as many Letters as Genders ... 32 at this point, but ALWAYS subject to change.

LG ∞

It makes him Malcolm Tom. Or Uncle X, I can’t remember which.

Uncle X was the classic Uncle Buck remake starring DMX.

I'd watch that.

the "Bug with a hole in his chest" scene was epic

Without a doubt. Look at the original political meaning of woke. Black nationalists don't want white liberal pity.

Yes they do.

Malcolm X has one of the best anti-government quotes of all time:

"Only a fool would let his enemies educate his children"

Imagine how modern wokesters would deal with Frederick Douglass if they had a real encounter with him and his political philosophy.

...lol, thanks.

The irony of course is that Thomas himself was an affirmative action appointment.

But his reasoning is right on this subject.

Yeah, I remember when George Bush Sr made it clear to everyone that the supreme court justice he was nominating HAD to be a black man before anything else was considered.

It was wrong when Biden did it too.

Because his nominee couldn't be qualified either. You are such a racist piece of shit. You are just human garbage.

Bush was smart enough not to say it out loud. But I doubt it was pure coincidence that the replacement for Marshall just happened to also be black.

And that has dogged his career for years. Which is exactly a point Thomas likes to make frequently. His treatment in the press has been, for decades, an unthinking affirmative action hire who clamped on to whatever Scalia, and then Alito, was saying.

Which is unfortunate, because he has clearly, clearly shown himself to be as qualified for the position as any, and one of the great jurists in our nations history.

Yeah, it makes his point rather than detracting from it. And whatever you think of Thomas, it's pretty hard to make the case that he isn't intellectually independent.

Thomas was a graduate of Yale and former head of the EEOC. He was very much qualified for the position. He is certainly more qualified than both Kagen, who had limited experience in government as a political hack for Obama and was a figure head dean of Harvard Law.

You think he was an affirmative action hire because you are a racist piece of shit and assume any black man is an affirmative action hire. If you were not a racist, you wouldn't be a Democrat or certainly not a white one.

Thomas was an affirmative action pick because Bush Sr. only considered minorities and women for the post. Same as Jackson.

So he knows what he’s talking about.

It’s not a “misunderstanding” of Thomas, Damon. It’s an intentional smear.

They mean well.

Affirmative action is nothing but blacks accepting the slave mindset. Affirmative action assumes that blacks cannot succeed on their own and their success is only the result of white people's willingness to assist them. To support affirmative action is to say that black people's success or failure in this society is entirely dependent upon the willingness of whites to allow it to happen.

Why any black man with any self respect would support such a thing is beyond me. The fact that affirmative action is supported by so many people in this country is a testament to the lasting nature of the moral harm done to this country by slavery.

Might I suggest that the reason that American Descendants of Slavery would support Affirmative Action is that we would like to have the same opportunities that were denied to us under Negative Action, AKA the status quo where we were specifically denied opportunities to succeed by both formal policy and cultural animus? Since, when it was well within the power of the white establishment to simply treat us as citizens, they found it impossible to do so unless compelled to do so by force of Law, we have become accustomed to believing that whites are simply incapable of accepting what Genesis 1:26 says about human beings. I even recall reading someone who posted that the U.S. was Constitutionally intended to only serve the interests of White male landowners. That would explain why, among other things, for most of U.S. history, it was either extremely difficult for blacks to own land, or their land was regularly devalued through such things as Redlining, and the use of eminent domain to build Interstate highways that divided black communities. Think about it, in the nearly 250-year history of this nation, black citizens have only been able to own land without fear of white efforts to either strip them of ownership or destabilize the economy so that their property was extremely devalued for the last 50 years or so, at least, by government edict. When that was ruled to be illegal, they just turned it over to the banking establishment. There are too many investigation reports concerning the improper valuation of property by appraisers and the unequal treatment of black loan clients by banks and lending institutions when it came to loans that it's actually amazing that we still give the U.S. government opportunities to simply treat us as citizens. We've certainly earned that right by now.

What does any of this have to do with affirmative action?

Well, if you want to get lessons from history, why not look to the history of the Balkan peninsula?

It's become a cliche, but Balkanization is what you get when you invoke past screwings against your forbears in order to inflict screwings of your own against those descended from the old oppressors, or who look like them, or who anyway are targets of opportunity.

"...Think about it, in the nearly 250-year history of this nation, black citizens have only been able to own land without fear of white efforts to either strip them of ownership or destabilize the economy so that their property was extremely devalued for the last 50 years or so, at least, by government edict..."

Since 1970 or so? You have a real problem with reality.

We’ve certainly earned that right by now.,

What right exactly? I coudnt really follow

The "right" to take white people's stuff?

Now tell me why you have the right to hurt a bunch of people who immigrated to America post-slavery and post affirmative action just because your ancestors were treated poorly by bloodlines that don't even exist anymore.

Protip: everyone has been treated poorly historically speaking. The egalitarianism of the 21st century is a modern phenomena that most of the world still hasn't accepted.

Nobody that would benefit from Affirmative Action today had to live through that period so no they haven't been oppressed. My father did grow up dirt poor in a segregated coal mining town and suffered actual racism and to this day I have never heard him call himself a victim so you and everyone else that wants to claim secondhand victim hood can fuck right off. He went from a dirt floor shack to the Marines to owning his own business and making a comfortable life for his family. He busted his ass and never asked for pity or a handout. He taught me when I was a kid that nobody owed me a fucking thing, if you want something you put in the work and earn it and never apologize to losers for working hard and being successful. I took that to heart and busted my ass, got into a top 10 college and a top investment bank. That's dirt floor shack to Goldman Sachs in two generations because we worked hard, failure and disrespect weren't tolerated and we worked to lift ourselves up. So you and whoever else can be the perpetual victim and wallow in self pity and continue to fail or you can say fuck it I'll do it myself and move forward. If you throw up your hands when things get tough or you blame others for your failures all you'll ever be is a bitter loser. But that's your own fucking fault, not the man, not the system, not an abhorrent and repressive system of slavery that hasn't existed in this country for 150 years. It's you, fucking own it.

And Malcom X was right. The most dangerous thing to a black man in this country is a liberal with good intentions (and other young black men but the liberals with good intentions won't say shit about that). You should listen to his speeches and learn something. He wasn't a perfect man but he was nobody's fucking victim. Fuck affirmative action.

You have any opportunities and rights that any white man has.

This is how it's done.

Not the first time this has happened.

Boost! 😀

He's the best ever.

We dont deserve him

GOOD

is stupid the idea of affirmative action is in front of SC in 2022

Spoiler alert, Uncle Tom accepted his role as a slave, yes, but he also chose to be whipped to death rather than give up the location of escaped slaves. Not exactly a complete traitor to the cause. Just sayin'.

Yeah, in the novel he was virtuous (if nonresistant), it was the stage versions which made him a buffoon.

I am making 80 US dollars per hr. to complete some internet services from home. I did not ever think it would even be achievable , however my confidant mate got $13k only in four weeks, easily doing this best assignment and also she convinced me to avail.

For more detail visit this site.. http://www.Profit97.com

All college applications, or at least those to government-run universities, or those that take government funding (basically all of them), should be anonymized, with no names or photos or geographic information.

At least one university that had discontinued the SAT/ACT requirement on the grounds that it would disadvantage some racial groups is bringing back the requirement, because non-standardized applications criteria (think letters of recommendation, international summer trip enrichment/volunteer activities, after-school activities, etc.) turned out to be more discriminatory than standardized tests (not surprisingly.)

A public university shouldn't be able to discriminate in any fashion, including affirmative action. Private ones should be allowed to whatever they want, in either direction.

Private Us take so much government $, w/some exceptions, that they have agreed to be bound by govt rules. Who takes the King’s shilling…..

The few views and statements credited Malcom X, I tend to respect. I can respect anyone who preaches self-reliance. There is nothing wrong with working together as a team, but it is the collective ideology that I dislike.

There are two ways to view federal law against racism: the goal which, of course, is laudable; and the effect which has only been partially successful while causing a lot of unintended collateral damage. Laws against discrimination fail on at least two fronts: how to define and target discrimination; and failure to actually punish actual discriminatory practices. Trying to punish people for discrimination who don't believe that they are actually racist not only fails to achieve the goal against racism or discrimination but creates a population of non-racists who resent the anti-racism social movement and resist the efforts. There is a difference between promoting the social trend that is happening anyway with or without government; and trying to push it along with badly-written laws.

Offsetting the SAT/ACT test score needed to be successful at an elite university for the sake of equity, and that is what it is, only sets those students up for failure because they do not have the skills to do well.

Long live CT. God bless him.

Sooo... Positive Christian National Socialism wasn't enough, and Clarence is now going full Malcolm X Islam? Does this restore chain-gang sentences for mothers who write to their daughters explaining the rhythm method of birth control?

Battling Biology?

Affirmative action is an affirmation of the differences among the races. Jews do not need Affirmative Action. Orientals do not need Affirmative Action. Asian Indians do not need Affirmative Action. Why does the forcibly favored race need Affirmative Action? There is an answer.

https://www.nationonfire.com/negroes/ .