A 25-Year Prison Sentence for Beating Up a Dog Is Not Justice

Frank Javier Fonseca's punishment, which may amount to a life sentence, is a microcosm for many of the issues with the U.S. criminal legal system.

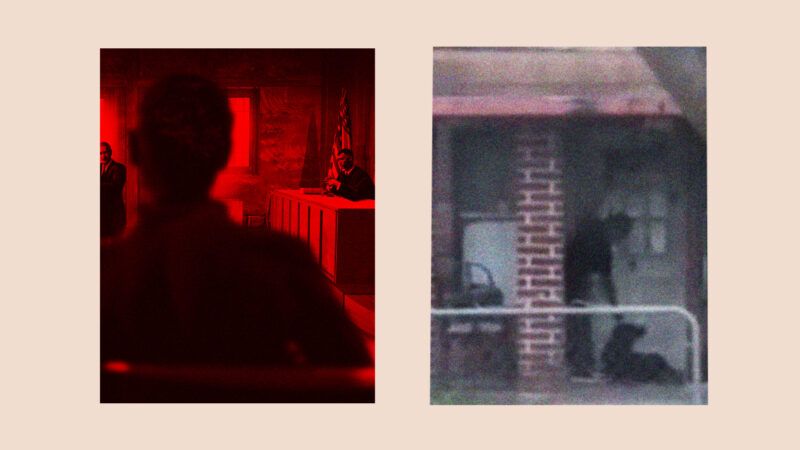

"The only, absolute and best friend that a man has, in this selfish world, the only one that will not betray or deny him, is his Dog," King Frederick of Prussia is reported to have said in 1789. There's a reason we still say something like that today, and it's because you can't say the same thing about people. Like Frank Javier Fonseca, a Texas man caught on video punching and kicking his Rottweiler, Buddy, for getting out of the yard.

In early February 2019, a passerby filmed Fonseca as he punched his dog on his porch. He kicked and choked him and hit him with a piece of wood. The video was shared with Animal Care Services (ACS) of San Antonio, which questioned Fonseca, who told them that that was his way of disciplining Buddy. The dog was removed from Fonseca's home, aided to a full recovery, and placed with a new family that presumably has a better handle on obedience training.

Fonseca, meanwhile, will spend the next 25 years in prison. While I love dogs as much as the next person, this is not justice. Fonseca's sentence for beating up his pet—which was his property under Texas law—grossly exceeds most punishments Texas dispenses for those convicted of assaulting a human being. Defendants found guilty of an assault causing physical harm face up to a year in prison. When the alleged victim is a government official, security officer, emergency services worker, family member, or date, that punishment may be anywhere from two to 10 years behind bars. And when someone brandishes a deadly weapon and causes serious physical harm, they may land behind bars for anywhere from two to 20 years.

The city of San Antonio boasted about forcing taxpayers to house Fonseca in a steel cage for the next 25 years—for $22,751 annually, well over half a million dollars total—for losing his temper and beating an animal. It "is one of the longest punishments for animal cruelty ever recorded in the state of Texas," Lisa Norwood, the public relations and outreach manager for ACS, said in a statement.

Taxpayers will subsidize Fonseca's living arrangements for longer than someone who assaults a disabled or elderly person, longer than someone who assaults their mother, longer than someone who takes a knife and inflicts serious, lasting physical damage to another human being, which the city of San Antonio acknowledges is not the case even with Buddy, who recovered from his injuries. It is also a considerably longer sentence than most receive for rape, which in Texas is capped at 20 years without aggravating factors. Fonseca's sentence is even longer than many defendants receive for murder.

So why is Fonseca, 56, getting what amounts to a life sentence for hurting his dog? While Norwood's statement suggests this is about sending a message to other dog punchers, the government says Fonseca had felony priors for crimes of retaliation and drug possession.

It's difficult to argue with a straight face that a years-old drug possession conviction should be used to increase his sentence for hurting Buddy. Fonseca's consumption habits may harm himself, but invoking that offense at sentencing is not about keeping San Antonio safe. It is about securing a sentence that would otherwise be impermissible under the law. Access to that kind of leverage is one of the primary reasons law enforcement groups oppose ending the war on drugs.

And while the same cannot be said for "crimes of retaliation," in which people threaten government workers, Fonseca had already paid his debt to society for that, just as he had for possessing drugs. It's certainly reasonable to consider a criminal defendant's history at sentencing—someone who assaults people over and over again, for example, should not receive the same sentence each time.

But even if you find animal cruelty to be abhorrent, as I do, a decades-long prison term is not the appropriate response to all objectionable behavior—something we often forget in the context of the U.S. system, which is utterly addicted to lengthy prison terms. Desensitized bystanders may view Fonseca's punishment as normal. It shouldn't be.

Show Comments (89)