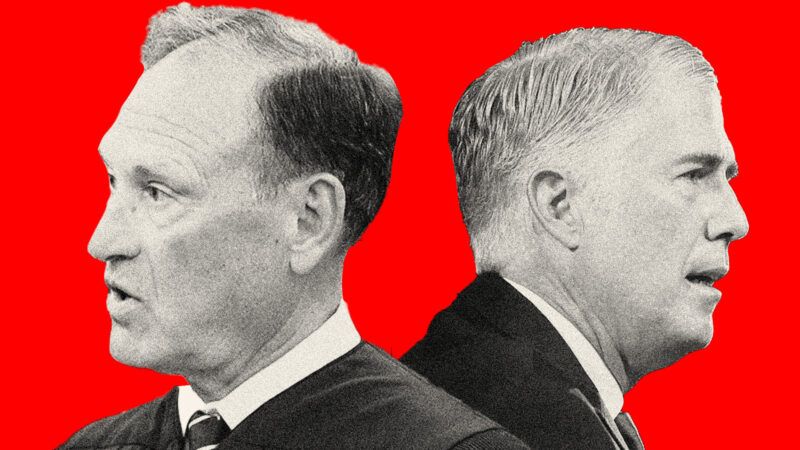

Gorsuch and Alito Butt Heads in Another Criminal Justice Case

According to Alito, Gorsuch’s opinion “veered off into fantasy land.”

When Supreme Court Justices Neil Gorsuch and Samuel Alito stand on opposite sides of a criminal justice case, it is safe to assume that criminal justice reform advocates will be cheering for Gorsuch. That maxim certainly held true today in the Court's 7–2 decision in United States v. Taylor.

At issue was whether a conviction for attempted robbery under one federal law, the Hobbs Act, also qualifies as a "crime of violence" under another federal statute, 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(3)(A). This matters because the additional "crime of violence" designation carries with it a second felony conviction and extra years in prison. Writing for the majority, Justice Gorsuch held that the "crime of violence" designation did not apply.

To qualify as a "crime of violence" under the federal law at issue, the offense must have, according to the statute, "as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another." Justin Taylor was charged with attempted robbery under the Hobbs Act. To secure that conviction, Gorsuch explained in his opinion, "the government must show an intention to take property by force or threat, along with a substantial step toward achieving that object. An intention is just that, no more. And whatever a substantial step requires, it does not require the government to prove that the defendant used, attempted to use, or even threatened to use force against another person or his property." In other words, while an attempted robbery occurred under the Hobbs Act, "no crime of violence" occurred under the terms of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(3)(A).

Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito each dissented from Gorsuch's opinion. Thomas blasted Gorsuch for a soft-on-crime judgment that distorted federal law, is "divorced from reality," and which "threatens public safety." Alito was not exactly complimentary either. "I agree with Justice Thomas that our cases involving §924(c)(3)(A) have veered off into fantasy land," he wrote. Gorsuch's "strict reading of the text," according to Alito, led to an absurd result.

In 2020 I wrote about the growing trend of criminal justice cases dividing the "conservative" judiciary. One of my examples involved Gorsuch and Alito clashing over the meaning of the Fourth Amendment, with Gorsuch advancing an interpretation that would cause the government to lose many more cases than it currently does while Alito countered with a far more deferential stance in favor of prosecutors and police.

Today's dispute over statutory interpretation in a criminal sentencing case represents yet another active front in this ongoing and crucially important judicial battle.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

IANAL and don't know the finer details of the legal definitions of "robbery" and "violence" under two different laws, other than remembering quite a few cases where definitions of the same word or phrase in different laws differ considerably. But as far as I'm concerned, the benefit of the doubt should always go against the government. They have given themselves too many advantages already.

Reading the opinion now but from the highlights, here's what happened:

Defendant, and an accomplice, tried to rob someone. The robbery went bad and the accomplice shot someone. The federal government makes it a crime to commit robbery with an "interstate component" (insert a 10-hour video of rolling eyes here) with an added extra penalty if it's a "crime of violence". The issue isn't whether or not the crime was or wasn't violent, but rather whether violence is "inherent" or "elemental" to the act committed. Basically, it's worse if the thing you are doing can't possibly be done without attacking someone. The SCOTUS is saying here that robbery doesn't inherently have a violent component to it so the defendant just gets his twenty years in the slammer, rather than having that time further enhanced because the crime actually committed was violent.

Thanks.

My first reaction was that of course robbery is inherently violent. Then I thought of shoplifting, or picking a pocket, or stealing a car, or burglary, none of which are inherently violent in their definition, and my second reaction was that only government could confuse something so badly, especially when it is not the criminal act itself at issue which must be checked for violence, but only the abstract definition.

Again, thanks for "clarifying" what is unclarifiable.

I mean, IANAL either, so I can't argue whether what the SCOTUS decided is correct or incorrect reading of the law. The dissent seems to be reading the words as if "crime of violence" describes the act actually performed (which no one is arguing that shooting someone isn't violent). It's all lawyers arguing over what triggers the penalty enhancement, whether it's actually doing something violent (you get extra prison time for hurting people) or whether the crime, in the theoretical, demands violence (you get extra prison time for committing crimes that can only end in people getting hurt). I think Reason is kind of taking a stretch to call this criminal justice reform because it turns out to be to the benefit of a prisoner in this particular case. Dude is guilty AF and no one disputes that he's going to spend a lot of time behind bars for what he did.

I even have made $30,030 simply in five weeks clearly working part-time from my loft. (res-32) Immediately when I've lost my last business, I was depleted and fortunately I tracked down this top web-based task and with this I am in a situation to get thousands straightforwardly through my home. Everyone can get this best vocation and can acquire dollars

on-line going this link.> https://oldprofits.blogspot.com/

shoplifting, or picking a pocket, or stealing a car, or burglary

Those are all technically distinct from robbery too. Robbery is theft directly from a person. And I believe a threat of force has to be involved. So it's a pretty tight distinction. But I'm with you. Benefit of the doubt should not go to the government.

I agree both in theory (government should never get the benefit of the doubt), but also wonder why it makes any sense to have a 'crime of violence' felony. Just increase the sentencing guidelines for actually violent crimes?

Or really, why are these federal crimes in the first place. Let the states prosecute these things.

They kind of have to be federal crimes, as the states cannot prosecute a crime committed in, say Washington D.C., or on a military base.

Great

I'm going to go read the opinion, also. Based on my brief understanding from the article, I'm actually feeling Gorsuch might be wrong on this one. The types of criminal justice reform I'm in favor of has little to do with punishment for violent crimes after a conviction; it's respecting the rights of the accused before they've been convicted, bail reform, nonviolent offenses (like simple possession), and excessively intrusive laws. Basically, I'm not looking for big reforms in robbery statutes, I'm fairly happy with how those work.

But I'll read it. Gorsuch is smarter than I am, by a lot, and he's usually well-reasoned in his arguments.

hlo

Thanks for the explanation n00bdragon. If I understand Gorsuch and the majority opinion correctly, one can politely and without any threat of violence commit robbery, that is, take something of value from another person. For example, if the robber says, "I'm not going to harm you but you need to give me all your money or I'll be upset with you," that is not a crime of violence. I agree with both Gorsuch, that such a robbery is non violent, and with Alito, that such a robbery is living in fantasy land.

I like when Alito whines. Usually a good thing.

So Gorsuch was trying to argue that an attempted armed robbery where one of the perpetrators shot someone was not violent? I suppose because the convicted man did not personally hurt anyone? Yeah, that deserves some ridicule. No wonder Root buried the facts of the case. Knee jerk rooting for a convicted criminal to win a decision is not laudable when the facts are not on your side.

No, he's arguing that the crime of robbery, as defined in the statute, does not require proving violence was used as an element of the crime, so it is therefore not a 'crime of violence', regardless of whatever happened in the commission of the actual robbery. I don't think anyone's disputing this particular robbery involved violence.

Thomas' dissent is SCATHING, holy shit.

Yet, the Court holds that Taylor did not actually commit a “crime of violence” because a hypothetical defendant—the Court calls him “Adam”—could have been convicted of attempting to commit Hobbs Act robbery without using, attempting to use, or threatening to use physical force. Ante, at 5; see §924(c)(3)(A). This holding exemplifies just how this Court’s “categorical approach” has led the Federal Judiciary on a “journey Through the Looking Glass,” during which we have found many “strange things.” L. Carroll, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass 227 (J. Messner ed. 1982).

Rather than continue this 30-year excursion into the absurd,

I would hold Taylor accountable for what he actually did

and uphold his conviction. Accordingly, I respectfully dissent.

He's pissed that the court overturned the sentencing based on a hypothetical set of facts instead of the facts of the case. Basically Thomas says, "Bring a better case to the court to challenge this statute because this fucker was violent, and deserves for the law to be applied properly."

Thomas is a great jurist. He is definitely the most rigorous thinker on the court in my lifetime.

Gorsuch, as far as I've seen, is also pretty great and has a thorough, thought through Textualist viewpoint. I look forward to more opinions from him.

When they disagree, I am very open to the likelihood that there is a lot of complexity at play in the issue. I may agree with one versus the other, but I think it is reasonable to allow that both have serious points to be made. Get us to a point where the judiciary is made up of Thomas-types arguing over the interpretation of the law with Gorsuch-types and our country will be so much better for it.

It was an armed robbery where one of the perpetrators shot someone. There was a use of physical force involved in the commission of the crime.

To conclude that because robbery does not necessarily require violence, the proven actual use of violence and threatening of violence in this particular crime can be dismissed is absurd logic.

Think of it this way: The judges are arguing over whether the +10 years sentence enhancement for a "crime of violence" applies to crimes which can only be done violently (the majority opinion) or whether it should be applied to any crime which involves violence, regardless of whether it requires it in the abstract (the dissent). No one is dismissing the crime as it happened at all.

My non-lawyer take on this is that cases like this result from too many laws.

Maybe there should be a concerted effort to clean up the statutes and make clear what is and is not a crime.

Find me a lawyer that agrees there are too many laws and I'll show you an unemployed person.

what if too many laws in all aspects other than that which the lawyer practices?

No matter how crystal clear the language might be, attorneys will argue and some judges agree the law is vague and not clear. That is what attorneys do, and judges being attorneys often go along for the ride through the looking glass.

https://www.zerohedge.com/political/impact-soros-funded-district-attorneys

I don't think Damon explained the case very well.

Taylor and an accomplice committed a robbery, and his accomplice shot and killed the victim. Taylor was convicted of Robbery. The issue is that the crime of Robbery is not necessarily violent (even though in this case it was). So, Gorsuch said the extra sentence for "violence" could not be added.

https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/supreme-court-rules-for-defense-in-federal-gun-sentence-case

No, you explained it poorly. "Robbery" is inherently violent. What they're arguing is that ATTEMPTED Robbery is not inherently violent. You can be arrested for attempted robbery before you ever had the chance to attempt violence or threaten violence, but robbery is inherently violent.

I think the 7 member majority was so excited to craft a new precedent, however, that they ignored the fact that this was a very violent case of attempted robbery and not a hypothetical.

It was an armed robbery where one of the perpetrators shot someone. There was a use of physical force involved in the commission of the crime.

To conclude that because robbery does not necessarily require violence, the proven actual use of violence and threatening of violence in this particular crime can be dismissed is absurd logic.

So the defendant didn't shoot anyone. What did _he_, not his accomplice, allegedly do that was violent? Was that proved in court?

Part of the problem seems to be that the statute redefined "robbery" so it doesn't require violence or a threat of violence. In it's common meaning, robbery is inherently a violent crime and there's no need to prove at trial that a particular robber was violent. But when Congress changed the definition, they messed that up; now that a nonviolent "robbery" is possible, due process requires a specific court finding of violence before it can be taken into account in sentencing.

Congress's second mess was allowing "violent crime" to be a sentence enhancement at all. Leave robbery in it's common meaning of theft by force or threat and add any years they consider appropriate for "violence" to the sentence range for robbery itself.

Rule of thumb, if reason supports something, question it extensively.