Zap Comix Were Never for Kids

Disreputable and censored comix improbably brought the art form from the gutter to the museums.

In 1969, in an atmosphere of simmering animus toward youth culture, an undercover agent from the New York Police Department's Public Morals Squad visited two bookstores to buy copies of Zap No. 4. This minor bit of commerce had violent repercussions. "This bearded guy pushed the door open aggressively and said 'OK, this place is closed down!'" remembered Terry McCoy of the East Side Bookstore. "I thought he was a street guy. I instinctively blocked the entrance. 'Hey, buddy,' I said, trying to calm him down and get him outside, 'what's the problem?' He said, 'You work here?' I said, 'Yes,' and he said, 'You're under arrest.'" McCoy, the boss, and another employee were all taken to the precinct and then the Manhattan Detention Complex.

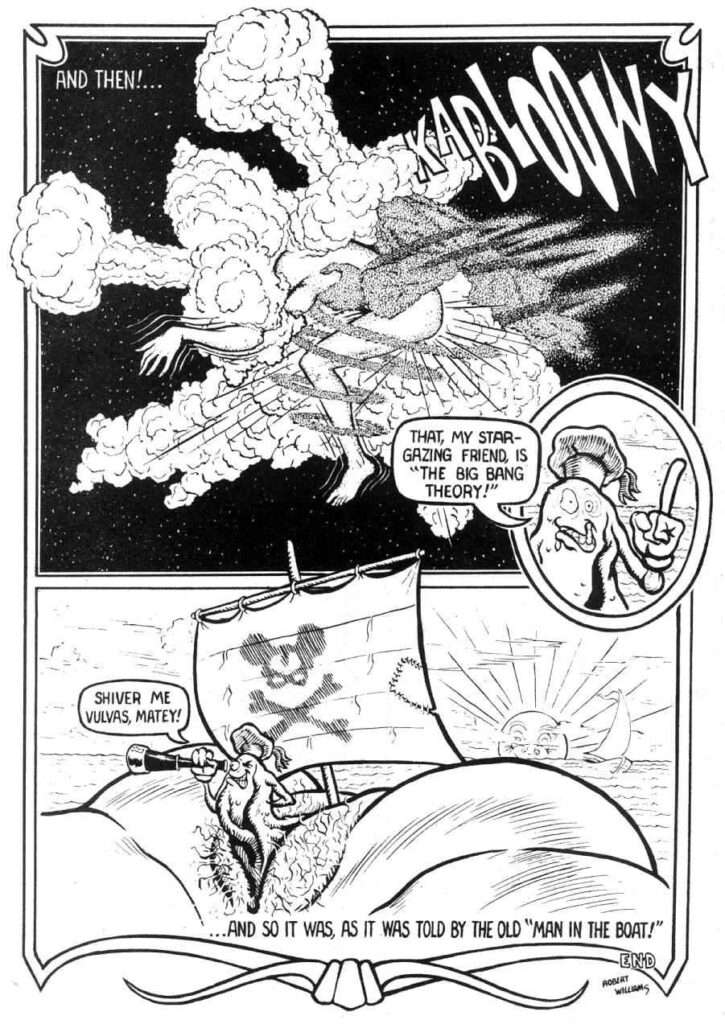

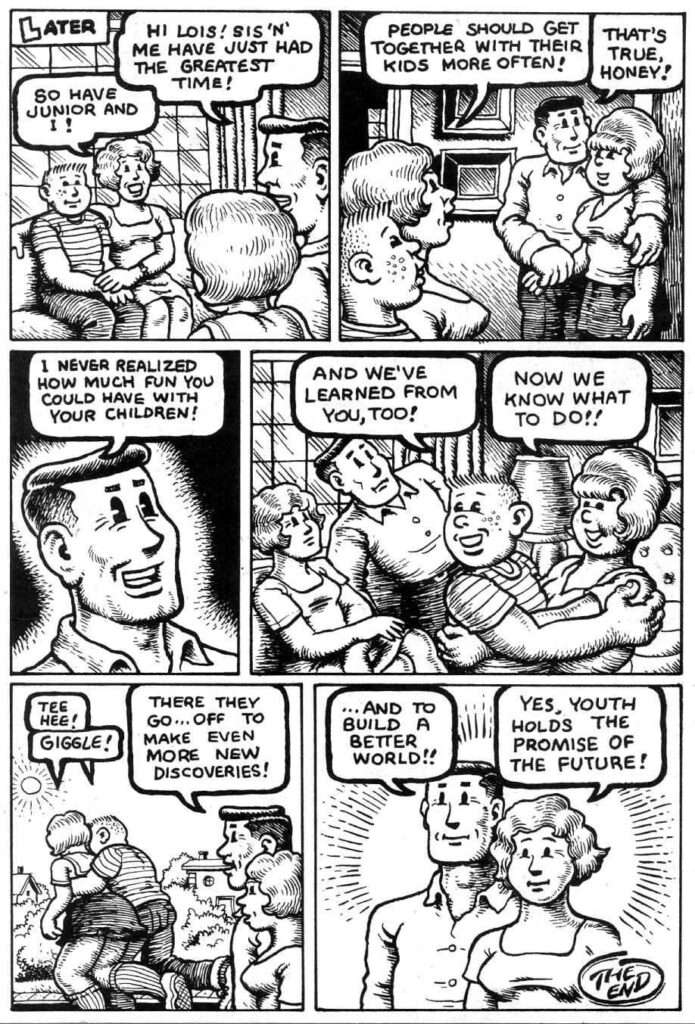

Zap No. 4 is an anthology with stories and drawings by seven different cartoonists: Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Spain Rodriguez, Robert Williams, and Gilbert Shelton. Their tales include everything from sexual torture to an anthropomorphic clitoris, but the star of the lurid show, the most unmistakably offensive and troublesome story—so far beyond what anyone might call "problematic" today—is "Joe Blow," written and drawn by Crumb. We see a father watching a blank TV, musing that he "can think up better shows than the ones that are on," who then stumbles upon his masturbating daughter. From there, things degenerate into an incestuous orgy, with the characters drawn to seem more toylike than human. In the end, after the dad declares "I never realized how much fun you could have with your children," the strip shifts into a mock-socialist propaganda mode. The kids, we are told, are "to build a better world!!" "Yes, youth holds the promise of the future!"

The New York Times asked Crumb about this comic in 1972: "What was your intention?"

"I don't know. I think I was just being a punk."

Just four years prior, Crumb had been making a living drawing funny greeting cards for American Greetings in Cleveland, but he'd transitioned into a career of blowing hippies' minds with cartoons in counterculture tabloids such as Yarrowstalks and the East Village Other. In 1968 he broke into the mainstream with his anthology Head Comix, published by Viking. He garnered praise from a variety of generational gatekeepers, and his art graced the cover of Big Brother and the Holding Company's Cheap Thrills, an album that topped the charts for eight weeks. And now he was inadvertently responsible for getting booksellers dragged to prison and forcing publishers into hiding from the authorities.

Revenge of the Smartass Rebel Cartoonists

Zap No. 4 was an example, an archetypal example, of what were called "underground comix." Its artists' work in other places—album covers, rock posters, underground newspapers, T-shirts—defined what it looked and felt like to be young and strange and rebellious (or to believe you were) in the late '60s.

Unlike most comic books sold in America, the undergrounds did not subject themselves to the authority of the Comics Code, whose seal emblazoned the top corners of every comic you were apt to find on a newsstand, in a drugstore, or on a convenience store rack. To get that seal of approval, your comic had to be middle-American wholesome. It had to eschew "profanity, obscenity, smut, vulgarity" and "suggestive and salacious illustration or suggestive posture" and any "ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group." None of these were things that Crumb and his colleagues could be relied on to avoid.

Underground comix (the x to mark them as distinct from the mainstream) were not distributed by the sort of jobbers that were trucking around Time, Better Homes and Gardens, or Family Circle. They were distributed by hippie entrepreneurs, some of whom might also be slinging drugs, and they generally appeared alongside drug paraphernalia (such as pipes and papers for help ingesting drugs, or posters that made you feel like you already had). Though some were periodicals, many were one-shots either by design or by their creator's lack of follow-through. They were not sold as ephemera to be destroyed at the end of every month with the publisher eating the expense of unsold copies, like mainstream comics were. More like books, they would sit on shelves getting more and more dog-eared by the hands of curious thrill-seekers who might not dare to actually buy them and take them home (or who couldn't afford to).

Underground comix creators didn't just do art differently; they insisted on doing business differently—and, in doing so, eventually changed the mainstream comics industry as well. They had no interest in dealing with the existing mafias of periodical distribution or the corruption of its returns system; underground comix were thus sold nonreturnable to independent retailers enmeshed in rebel youth culture, without outside sponsors' ads coming between their message and the reader. Most importantly, the artists themselves remained the owners of their work. They were paid royalties like real authors (at least theoretically) and not merely upfront page rates as work-for-hire; and underground comix publishers printed and distributed what the artists chose to create, not vice versa.

Much of what made America juicy, zesty, strange, scrappy, devil-may-care, irresponsibly fun, and chaotically strange in the past half-century flowed through and/or out of this loosely assembled band of brothers and sisters: from hot-rod magazines to funny greeting cards, biker gangs to homemade mod clothing, psychedelic rock to science fiction, cheap girly mags to women's liberation, smartass college humor magazines to karate, Wacky Packages trading cards to surfing, communist radicalism to born-again Christianity, transsexualism to graffiti. They fought and lost legal battles with Disney and vice squads across the nation; they labored for 25 bucks a page or less and reshaped their despised art form into a now essential part of the cultural repertoire of any educated hip adult.

Unlike some other countercultural pop culture products—say, rock music—underground comix were genuinely subterranean, unsupported by major corporations or distributors. They were mostly a dark secret you needed to stumble across in the search for other quirky or forbidden kicks, or be initiated into by a previous acolyte, like some occult rite of passage.

Despite, or because of, that, underground comix became an essential accoutrement of a counterculture life, even as they frequently mocked, satirized, and critiqued counterculture life. They were absurd, scatological, goofy, innovative, scary, beatific, thrilling, heartbreaking, and sometimes shoddy, but in all their manifestations they brought pleasure, insight, and bewilderment to millions while seemingly designed to have their off-register, scrap paper, cheaply printed, stapled bodies fall to pieces in a damp rack in some grotty group house's bathroom damp with Bronner's residue. Still, many of them have been carried into the consciousness of later generations via pricey, highly designed hardcover box sets (or on museum walls).

Underground comix were born of smartass rebel kids yearning to push back vigorously against the limits of what their culture considered acceptable or allowable. These young artists were nearly all motivated at least in part by the knee-jerk censorship of the 1950s. In that decade, respected psychiatrists, Senate subcommittees, and mothers across the nation had decided comic books, especially the ones smart weird kids loved the most, had gone too far. Mainstream comic companies reacted with the self-imposed Comics Code, and the publisher these kids admired the most—EC Comics, home of Tales From the Crypt, Shock SuspenStories, Weird Science, and Mad—shut down all the horror and science-fiction stuff and turned Mad into a magazine. And eventually the censors came for the undergrounds too.

Sell a Comic Book, Go to Jail

The managers of those two stores selling Zap were convicted of selling obscene material and fined $500 apiece—almost $4,000 in today's money. It wasn't the last time an underground comic got someone into legal trouble. Even the famed Beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti had to go to court in 1970 to answer for his City Lights Bookstore selling Zap No. 4.

A Van Nuys, California, man running an explicitly "adult books/art film" shop called Swinger's Adult Books was arrested for selling Zap and Crumb's Motor City Comics in September 1969. A vice officer involved explicitly said, as reported in the Hollywood Citizen-News, that the "warrant was issued on these two publications because they had also been used as examples of pornography in other legal cases. Precedent-setting court action would aid in prosecution…adding that 'dirtier' material was being sold here but was not involved in the arrest." The arrest was triggered by complaints from a local women's club, a representative of which noted that "the type of material to which we refer does nothing to aid in the development of a healthy mental attitude."

Ripples of fear from the Zap busts spread. Comics collector Glenn Bray told Bijou Funnies editor Jay Lynch he was having a hard time finding the new issue in the Los Angeles area in June 1970, warning him that "L.A. is really down on all the underground comix—the cops hassle everybody too much, and I guess the vendors don't seem to think [selling comix] is worth the trouble." Young Lust, one of the best-selling titles of the early 1970s, ended up with hardly any New York newsstand presence for a while because distributors there were, to quote Young Lust editor Jay Kinney, "chickenshit" about naughty comix after the Zap bust.

Bud Plant, an early comic book store and distribution pioneer, remembers at a Phoenix, Arizona, convention in the early 1970s having "a bunch of underground comix there, and we were at a Ramada Inn or something like that. One of the kitchen staff or one of the cleanup people that night had wandered into the dealer's room after it was closed, picked up some of my undergrounds and took them back to the kitchen, was reading them and then left them laying around. So the next thing we knew the hotel people came in to [the convention organizer] and said, 'We didn't know you guys were selling pornography here.'" The organizer did some fast talking, the undergrounds were put away, and no one got arrested.

At another convention, in Berkeley, California, organizers built plywood walls around their display of potentially obscene art and slept in the makeshift room all night to protect it.

When the folks at the comix publisher Last Gasp shipped titles to England, they would deliberately bury the more gnarly items in the middle of the box, below slightly more anodyne ones, and cross their fingers about how deep the Brit customs boys would dig. Felix Dennis, later a billionaire publishing magnate, was sentenced to nine months in jail for violating Britain's Obscene Publications Act for his role in publishing and distributing the underground magazine Oz, though he served less than a week before public pressure on his behalf got him out pending appeal, and he ended up with a suspended sentence. One of the offending things Oz ran was an image of a sexual Crumb cartoon with the head of the British children's favorite Rupert the Bear superimposed.

In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to take on an appeal of the New York Zap case. That same year, in Miller v. California, the Court issued a decision with fateful effects on the underground comix business. This ruling allowed the standards of obscenity to be fine-tuned to specific jurisdictions in which an item was sold, so the things that might be legally tolerated in San Francisco didn't have to fly in Kankakee, Illinois. The specific facts of the case involved a porn mail-order catalog, but it hit hard at the business of selling cartoon images of sex.

Miller came down in June. By August, Denis Kitchen—founder of Kitchen Sink Press—was sending out a form letter to his artists/creditors, summing up the perfect storm of woes haunting their little cottage industry, starting with the aftermath of that decision: "Underground comix have been the target of prosecutors in several areas. We have received reports of busts in New York, New Jersey, and Iowa, and unconfirmed reports of busts elsewhere. In one instance in New York, the owners of a head shop were arrested and dragged out in handcuffs for selling underground comix."

A sympathetic insider at the police department gave a warning to Don Schenker, majordomo of Zap No. 4 publisher Print Mint, a day before he was raided. He was thus able to get most of the more obviously obscene comics out of their warehouse and into a safer space just before the cops came. For the next year he sold the likes of Zap No. 4 bootleg-booze style, only to people he personally knew, with the offending books never being on Print Mint property. He was not convicted.

Even art galleries were not immune to vice raids. The first Bay Area art show dedicated to underground comix art at the Phoenix Gallery was raided and gallery owner Si Lowinsky arrested. He was acquitted, even though he had been selling the very porny Jiz and Snatch comics, copies of which were seized. Peter Selz of the University of California, Berkeley's art museum, called as an expert witness, judged them "not the greatest of art, but it certainly makes one laugh." The jury, Lowinsky later said, "decided that people have a right to symbolically represent all sorts of outrageous acts, and that society has no right to ban such representations."

But not every case ended in an acquittal, and every arrest could have a chilling effect. As Zap cartoonist Robert Williams would later say, "Me and Crumb, we knew the things we drew, someone was going to have to pay for." And they did, mostly shopkeepers and clerks, in numbers Williams swears were in the hundreds.

From the Gutter to the Gallery

With zero institutional support, the undergrounders drew not just opposition but condemnation—cultural, artistic, and legal. Still, they couldn't be stopped. Underground comix brought comic art to the courtroom, but down the line they brought the form and its creators to Pulitzer Prizes, New York Times bestseller lists, MacArthur "genius grants," Emmys, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The artists' fates were intertwined—and varied. Robert Crumb became a wealthy expatriate icon; S. Clay Wilson, who helped make Crumb what he is, lay brain-damaged for more than a decade in his rent-controlled San Francisco apartment from injuries caused by his out-of-control drunkenness. Art Spiegelman won a Pulitzer Prize and a Guggenheim Fellowship and became the leading intellectual spokesman for the entire art form; Jay Lynch, one of his best friends, who as a teen had passed out copies of the absurd cartoons they drew together to strangers, died nearly destitute and forgotten. Bill Griffith has thrived for decades at the eternal summit of the working cartoonist, a syndicated newspaper strip, while his old pal Roger Brand, who inspired him to create that strip's central character, Zippy the Pinhead, died decades ago as a burned-out speed freak selling pages to strangers for beer money. Robert Williams can pull in high six figures for a single painting, while Trina Robbins was driven out of drawing entirely by the toxic psychological aftereffects of gendered interpersonal warfare in their tight little scene.

The skeptic might dismiss underground comix as the jokey sick nonsense a hormone-raged hostile smartass adolescent boy might be scribbling in his notebook in the back row, bored and resentful of his teacher. A lot of it is like that. Yet so much would be different without the underground comix creators and their influence, from the look of the modern New Yorker to the classic iconography of rock 'n' roll. No mainstream New York imprint would be publishing graphic novels without them, nor would major universities be teaching comics aesthetics or history. The Simpsons would not exist, nor would any modern adult animation. Even the modern superhero comic would be wildly different—Alan Moore, the British writer of Watchmen, first broke into the U.S. comics market in an issue of the underground Rip Off Comix.

Underground comix gave a later generation of (im)maturing cartoonists something they needed to thrive: a sense of permission to dare to be who they could and wanted to be, to dig to the core of their talents and selves. It meant a lot, and it still does.

This excerpt is adapted from Dirty Pictures: How an Underground Network of Nerds, Feminists, Misfits, Geniuses, Bikers, Potheads, Printers, Intellectuals, and Art School Rebels Revolutionized Art and Invented Comix by permission of Abrams Press.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Crickets. Tumbleweeds.

A silent intersection.

Nothing was spoken.

Public morals squad

Hated underground comics

Locked up outsiders

Not only were they never for kids, but they were never funny either.

^ This.

They may have been ground-breaking but they were poorly-written, ugly garbage.

I wish more talented cartoonists had tried to push boundaries.

Had they been other than what you term "poorly written, ugly garbage" they would have been mainstream. And accomplished absolutely nothing.

Talented cartoonists don't have to be mainstream.

Or well behaved.

I know a lot of Crumb's stuff was beyond shock value, and he was often "just being a punk." But sometimes it is good to have someone just stick it in the eye of established mores.

BTW, if you haven't already check out his illustrated rendition of Genesis. Makes the entire thing both readable and comprehensible, as well as entertaining. I wish could have done the entire Bible; it could possibly inspire a Judeo Christian renaissance.

With Moses as Mister Natural, the "Keep On Truckin!" man, crossing the Red Sea? Or Jesus doing the "Keep On Truckin'" step wirh a cross on his backt all the way to Golgotha? 🙂

I seem to recall seeing in a relative's old Hippie magazines a comic strip that looked R. Crumb-y (is that the adjective?) It was portraying Hippies drinking Ripple and acid-tripping and fucking in the midst of a nuclear Apocaolypse and with the usual "Born-Again" spiel about making sure you're "saved" before you die. And it concluded with something like: "Heaven: More Than Just 'Pie-In-The-Sky!'"

I guess you could say it was like R. Crumb feeding Jack Chick some "stepped-on" cornpone. 🙂

"...portraying Hippies drinking Ripple and acid-tripping and fucking in the midst of a nuclear Apocaolypse and with the usual "Born-Again" spiel about making sure you're "saved" before you die. And it concluded with something like: "Heaven: More Than Just 'Pie-In-The-Sky!'"

How one can not think that is funny, I just don't know. Maybe it's just me, but that kind of stuff make me piss my pants laughing.

It was definitely weird. Perhaps it was an outreach attempt to Hippies by the "Jesus Freaks" Movement of the time.

Another thing I remember from publications from that time were the full-page ads from Rev. Kirby J. Hensley who headed The Universal Life Church, whose creed was "Do Only That Which Is Right" and who offered free lifetime ordination as a Universal Life Church Minister. They also sold religion and philosophical courses as well as more specialized Ministerial Titles and Credentials. In the Information Age, they started offering the free Ordination online with a printable certificate.

And sure as the world they're still around:

Universal Life Church

https://www.ulc.org/

Some have used their ordinations to do neat things like attempt to argue Conscientious Objection to being drafted into Vietnam (how successfuly, I don't know) and performing the earliest same-sex weddings in the U.S. Even Madalyn Murray O'Hair took up the Ordination as kind of a gag.

As Jerry observed: "What a long, strange trip it's been..." 🙂

Gilbert Shelton's comix (conspicuous in their absence) were hilarious! Back then we had hilarity-enhancers that hugely increased the market for movies and fun reading. Thanks to the Kleptocracy, fentanyl overdoses replaced all that.

"I can still use my snout!"

-Wonder Warthog

Much of what made America juicy, zesty, strange, scrappy, devil-may-care, irresponsibly fun, and chaotically strange in the past half-century flowed through and/or out of this loosely assembled band of brothers and sisters: from hot-rod magazines to funny greeting cards, biker gangs to homemade mod clothing, psychedelic rock to science fiction, cheap girly mags to women's liberation, smartass college humor magazines to karate, Wacky Packages trading cards to surfing, communist radicalism to born-again Christianity, transsexualism to graffiti.

What made America juicy was brevity. It's a Puritan holdover. Consult Warriner's English Grammar for more details.

brevity is the soul of wit

Polonius in Shakespeare's Hamlet

"I never realized how much fun you could have with your children," the strip shifts into a mock-socialist propaganda mode. The kids, we are told, are "to build a better world!!" "Yes, youth holds the promise of the future!"

The New York Times asked Crumb about this comic in 1972: "What was your intention?"

"I don't know. I think I was just being a punk."

... 50 yrs. down the road, little Scotty Shackford cribs his manifesto.

Words and ideas are dangerous.

I bought and Issue no.4 along with other back in the early seventies. Loaned them to a friend and he deliberately destroyed them.

Ahh, the memories: Mr. Natural and Flakey foont, the Furry Freak Brothers, biker gang known as Screamin' Gypsy Bandits, The Checkered Demon...my fave, along with some of the best psychedelic artwork not seen since.

Those were the days.

New York Police Department's Public Morals Squad

You're saying you didn't set a police car on fire during a BLM riot? Get in the car, asshole.

Look at the dates in the article. The heat came off of Haight-Ashbury's favorite and Austin, Texas' second-fave literature (after Furry Freak Brothers and Fat Freddy's Cat) after a single electoral vote went to the Libertarian Party in January of 1973. Ain't that the damndest coincidence? It's almost as if every vote cast for Libertarians John Hospers and Tonie Nathan packed 11,000 times the usual clout! All at once Republican Comstock laws banning birth control and "disloyal" material hit the dustbin of fascist history.

'Just goes,to show ya,huh?... 😉

Bacon Story--From Grumpy Old Men

https://youtu.be/u05gAMMazWY

Sorry, Grumpier Old Men.

My mind was irreparably damaged by all the Zap Comix I read in high school. Underground comix, filled with depravity and filth turned me into a moral degenerate.

I still dream of having illicit sex (the best kind!) with Ambrosia Sweetcheeks.

And you are better off for it.

One of the frequently-used tag-lines from Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In, after a person gets conked on the head by a Cop or a Judge or other authority figure was:

"And I am a better person for that!" 🙂

Things like that made me wonder if George Schlatter had Libertarian-minded folks for comedy writers. It was filled with one-liners like that. For example, one of the actors, Jo Anne Worley, had a sign that said: "Mao-Tse Tung Plays Monopoly!" 🙂

Speaking of, I suspect w lotcof Rad-Fems got their ideas of feminine beauty from R. Crumb. 🙂

Crap.

Stupi9d hippy leftist crap. That's what it was then. That's what it is now. With a 'message' as subtle as a sledgehammer.

The left can't meme. Not now. Not then.

And if you laughed at any of this garbage you were either high or retarded and laughing because it's what you thought you were supposed to do.

There WAS a great underground comics scene--but it wasn't this garbage.

Some of it was pure shock value, but the point was to question everything and be an iconoclast to all.

Often it was just weird, but if you couldn't laugh at Zap etc. you either took yourself too seriously [and I'm thinking that was sort of the point of most of it, to point that out] or just lacked a sense of humor.

It was comix, after all. And if you didn't like it absolutely no one told you that you should indulge in it.

Um tut sut?

Sure, why not?

Meatball!

I have a fondness for that era as well. And though I also do not like the restriction of the comic book code, I also dislike this story you see a lot of underground comix being a refuge for talent and creativity from the bland mainstream of comics. There was a lot of talent working in DC/Marvel in those days, too. The topics were different but there was artistry to be found.

...but did they take their young kids to drag shows?

More like taking the drag show [and various other perversions] to the kids.

Robert Williams is a favorite. A friend was lucky enough to have one of his own pieces hanging next to a Williams painting at C-Pop in Detroit.