Tariffs Are Adding to Inflation. Biden's Commerce Secretary Says Repealing Some 'May Make Sense.'

Tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump and kept in place by President Joe Biden are costing consumers $51 billion annually.

Tariffs raise prices. That is literally the thing they do.

Politicians often try to obscure that basic fact by talking about tariffs' second-order effects. They say that applying taxes to imported goods will help protect domestic manufacturers—by raising prices on foreign-made goods, making them less competitive. Or, as former President Donald Trump frequently did, they might say that tariffs can promote national security—by making foreign goods more expensive, encouraging investment in domestic industries.

The extent to which any of those second-order effects actually happen is subject to debate, and the past few years suggest that the trade-offs involved are not worth it. But if you leave aside that political debate, there's still a basic, inescapable fact: Tariffs, by design, raise prices.

After nearly 16 months in office, facing historically high price increases, the Biden administration seems to have finally discovered how tariffs work.

Asked Sunday on CNN's State of the Nation whether the administration would consider rolling back some tariffs to fight inflation, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo admitted that it "may make sense" to do that.

Don't get too excited. With her previous breath, Raimondo suggested that the Trump-imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum would remain in place "because we need to protect American workers and we need to protect our steel industry; it's a matter of national security."

There's that typical tariff obfuscation. What Raimondo is really saying is that the administration believes mandating higher prices for steel and aluminum—and thus higher prices on every American, and every American business, that consumes steel and aluminum—is more important than helping to bring down inflation. And that's just days after her boss assured us that he would "take every practical step to make things more affordable for families."

Still, Raimondo added that "there are other products, you know, household goods, bicycles, et cetera, and it may make sense. And I know the president is looking at that."

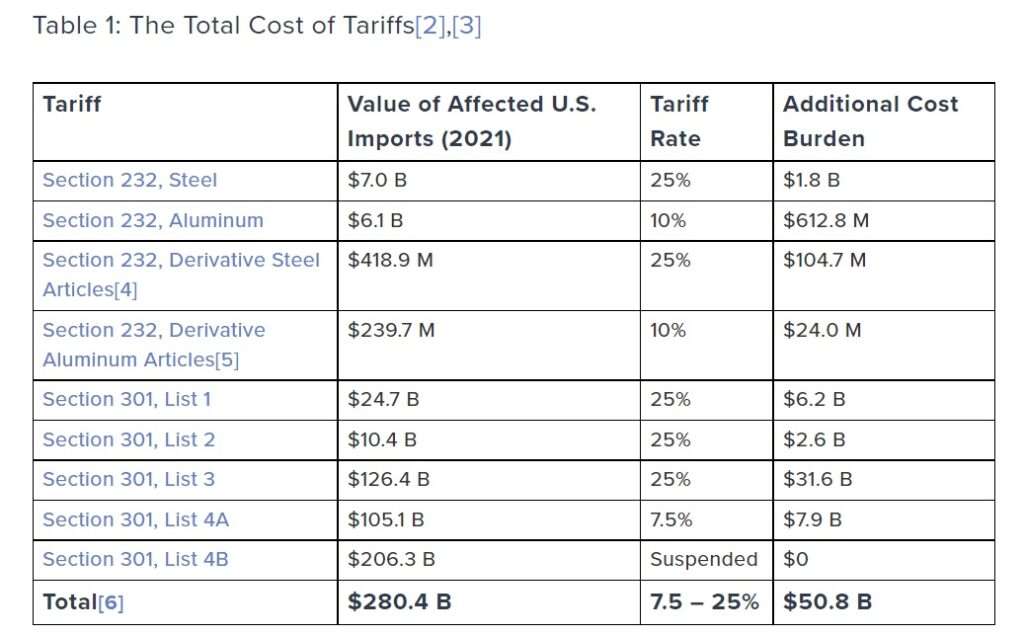

The set of tariffs imposed by Trump and maintained by Biden—including those on steel and aluminum, along with a host of imports from China—is applied to approximately $280 billion of imports every year. Those import taxes add about $51 billion annually to Americans' consumer costs, according to an analysis by the American Action Forum, a pro-market think tank:

As the above chart shows, the tariffs imposed on goods imported from China under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 are much costlier than the more well-publicized tariffs on steel and aluminum (and on their derivative parts). They also apply to a far wider range of consumer goods than most people probably realize, covering everything from bicycles to car parts, camping gear to children's toys, sports equipment to clothing, and a whole lot more.

About two-thirds of all imports from China are now subject to tariffs when they enter the United States, with the average tariff being 19.3 percent. That's six times higher than the average tariff on Chinese-made imports before Trump's haphazard trade war began.

Thanks to all those tariffs on consumer goods, the federal government has collected record levels of tax revenue from tariffs in recent years. And American consumers have seen huge price increases.

Because, yes, tariffs raise prices. That's what they do.

Of course, ending tariffs on Chinese imports won't single-handedly solve the inflation problem. There's some debate over the extent to which tariffs are contributing to inflation. Ed Gresser, a former assistant U.S. Trade Representative who is currently the vice president and director for trade and global markets at the Progressive Policy Institute, a center-left think tank, pegs the figure at about 0.5 percent annually. Experts at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), a trade-focused think tank, say it's about 1 percent.

But there's general agreement that tariffs are having some effect, even if a marginal one, on prices. "Tariffs make imports more expensive; importers often pass these additional costs through to consumers, leading to higher prices and inflationary pressure," PIIE concludes in its analysis of the link between tariffs and inflation.

In a speech last month, Biden promised that corralling inflation was his "top domestic priority." If that's true, the tariffs have to go. All of them. No more obfuscation about the alleged merits of steel and aluminum protectionism versus higher prices. Either combating inflation is truly the administration's top priority, or it isn't.

Raimondo's comments on Sunday suggest it isn't yet. But at least the White House is finally, slowly, admitting that tariffs raise prices.

That's the thing they do.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

How dare Reason be consistent in their criticism of tariffs!

test

interesting, I’m being blocked from posting in the roundup thread – literally a 403 block message – but not on other threads.

I got that for a minute too, but eventually it stopped

Might just be shitty web dev stuff. Reason is not unfamiliar with that.

figured enb was tired of me mocking her ideas lol

I was still allowed to comment, lol.

Of course, ending tariffs on Chinese imports won’t single-handedly solve the inflation problem. There’s some debate over the extent to which tariffs are contributing to inflation.

Is it perhaps due to the fact that the tariffs were around for quite a long time without runaway inflation, and there was a more direct effect-runaway spending and blank checks-that did cause inflation?

Inflation and higher prices are not the same thing.

Don’t confuse Boehm with facts. Their corporate overlords have an agenda to push, an agenda that includes using Chinese slave labor and flooding the country with illegal migrants, both policies that do indeed lower prices while also destroying the country.

You forgot to mention the intentionally introduced market uncertainty and supply constriction in energy

ERIC BOEHM

Reporter

Who do you plan to vote for this year?

I am currently not registered to vote in Virginia, where I live. If I change that before the election, I will vote for Jo Jorgensen—unless I believe there is a chance that Joe Biden will somehow fail to win Virginia, in which case I will vote strategically and reluctantly for Biden.

If you could change any vote you cast in the past, what would it be?

I can’t imagine thinking a single vote is valuable enough to spend time regretting.

https://reason.com/2020/10/12/how-will-reason-staffers-vote-in-2020/

#ReturnToNormalcy

So he voted Libertarian Party. What’s the problem?

Hahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahaha… phew.

Yeah Brandi, okay.

All government taxation and/or spending effectively raises prices. Tariffs on hostile, totalitarian nations at least serve a purpose.

But for some reason, Reason passionately and irrationally hates tariffs and clings to the absurd belief that trade with communist nations employing slave labor is governed by the laws of free markets.

$51 billion is less than the amount of money Congress has wasted on inflaming the Ukraine war. That’s what libertarians should be upset about.

I dislike tariffs because they’re an inefficient method of controlling prices. The best ways to do it are to abolish the minimum wage (forcing labor to compete on the free market) and to dismantle regulations, to drive down manufacturing costs. The reason so much manufacturing went overseas was to escape government regulations, so trying to punish them after the fact by instituting false price controls doesn’t solve it.

Manufacturing needs stability, as well, and they’re not going to return manufacturing jobs to the US unless they have strict confidence that they won’t be regulated out of existence 2 years after making a heavy initial investment. You need investor confidence. It’s why nobody will sink any money into Venezuela-that’s the same reason oil companies are afraid to start drilling anywhere in the US while Biden is in office. A ton of resources are spent upfront getting in position to create and produce things before returns come in, and companies won’t shoulder that cost unless there’s confidence they’ll survive until their gains are realized.

I agree with your first paragraph – there was much we could have done to lower cost to be producers here. However, it isn’t a given that reducing those costly barriers would necessarily result in us being competitive with unfree nations.

Your ideas should have been a first step if our political class was actually interested in sound governance. Tariffs had the bonus of having little congressional oversight to enact.

Nations don’t compete economically. That’s a protectionist fallacy.

Tariffs on hostile, totalitarian nations at least serve a purpose.

Tariffs are not imposed on nations. They’re imposed on we the people. Foreign nations don’t pay them. We do. In the form of higher prices.

you need to start using your head rather than spew neolib corporatist propaganda

First he would have to learn something other than neolib corporatist propaganda. Garbage in, garbage out.

What I fail to understand is where those that feed on garbage get the balls to spew it onto forums where there are people that know better. There is something about the propaganda that encourages its idiotic repetition.

I assume Mr. Boehm didn’t study calculus. Consumer price inflation is the derivative of the a hypothetical price equation. But, in the hypothetical price equation tariffs are a constant. Which means they have no effect on inflation. Even if tariffs are a proportion of pre-tariff price, they disappear in the calculation of directional moves in inflation. In short, no, cutting tariffs doesn’t reduce inflation. It results in a one-time price cut. I’m opposed to tariffs, but pretending removing them will reduce inflation is just a lie. I’m not sure if Boehm understands this. And I’m concerned if our own government doesn’t understand this.

Anyone buy items from Ebay Europe? Postage has climbed for small items from under 10 pounds or Euros to over 30. In Italy I was quoted a postage rate of 50 euros for a 15 euro item. That is all government induced but I guess none of the PMs are orange or American so all is good.

Tariffs are taxes. Levied on domestic importers and consumers. Why do Republicans defending taxes? Jeepers Cripes, tariffs used to be a Democrat/Union core plank, now the Republicans consider them sacred.

Small government Republicans? Where are you? Did you ever exist?

I believe that the small government low taxes Republicans left the party soon after the elections of former President Trump. The TV and Internet ads are flying at us. Republicans want to cut taxes. I am guessing if you asked about lowering tariffs you could hear a cricket chirp.

The leader of The Party likes tariffs. That means that they must be rationalized and defended, and anyone who says different is a leftist.

Once upon a time the leader of the party was not a president or former president. Nixon was never the leader of the party. Ford was never the leader of the party. Bush I was never leader of the party. Bush II was never leader of the party.

And to be fair, neither was Reagan. Although he was accorded a lot of respect, he never got to dictate any agenda while he was not in office.

It’s a cult of personality, like the president before him, and it’s scary. I pointed this out years ago, and that’s one of the many reasons I’m so hated by conservatives. Because I’m right.

Don’t forget the consistent hypocrisy.

“The benefits of a tariff are visible. Union workers can see they are ‘protected.’ The harm which a tariff does is invisible. It’s spread widely. There are people that don’t have jobs because of tariffs, but they don’t know it.” — Milton Friedman

After thinking about it, he isn’t just the leader of the party, he is the party.

Inflation is causing prices to go up, and tariffs don’t help. Reducing them could take an edge off inflation.

Ridiculous. Inflation runs at over 8% per year. Eliminating all tariffs would be a one-time reduction amounting to a fraction of one percent.

Sounds like the January 6th hearings finale will be a full-blown propaganda session.

https://www.axios.com/2022/06/06/jan-6-committee-adviser-james-goldston

Already cringeworthy.

Wrong thread.

Personally, I like to see the format as a cage match between the former President and Liz Cheney. I am guessing that Cheney would accept and the former President would claim executive privilege. Because only one of the two has real balls.

Lol at attempt to make Cheney a stalwart person

Unrepentant neocons are so hip and dreamy nowadays.

Goldston = Goebbels + Riefenstahl

Open border globalists like boehm just can’t wrap their mind around tarrifs.

Can protectionist nationalists like Truthteller1 wrap their minds around “tariffs,” despite not being able to spell it?

Christ almighty, “inflation” is not a fancy synonym for “higher prices”, you ignorant blowhard.

Tariffs, insofar as they have any effect on inflation, cause it to be lower, because, like all other Federal taxes, they reduce the money supply. You quite literally cannot “fight inflation” by cutting Federal taxes, whatever other virtues Federal tax cuts might have.

The only ways for the Federal Government to fight inflation are tighter monetary policy and tighter fiscal policy. The former is a Federal reserve matter. The latter means less spending and/or higher taxes.

Taxes neither reduce nor increase the money supply, since the government spends every dollar it takes in in taxes

Taxes would reduce the money supply of the government used the revenue to reduce debt.

Um, no, not under current conditions.

If government spending were tied to tax receipts, such that every dollar in revenue resulted in a new dollar of spending, and every dollar of reduced revenue cut spending, then your claim would be true. Since states in general balance their budgets rather than running deficits and surpluses, that’s a pretty decent statement about state taxes.

Back when there was at least some effort in pretending to care about balancing the federal budget, it was also true that more revenue would encourage more spending and less revenue would encourage declines in spending growth, so it was approximately true about Federal taxes.

But the actual situation with the federal government under current political conditions is that spending is mostly independent of taxes. Under these decoupled conditions, both increases in spending and decreases in taxes increase the money supply.

The movement is packed with Austro-conservatarians who decry fiat currency while judging present-day fiscal policies as if we were still on a gold standard. I don’t know if they can’t process that when monetary policies change, fiscal policies must also change accordingly, or if they believe pretending that our currency is backed by a commodity, when it isn’t, is more virtuous or likely to produce closer-to-ideal results than adapting to the reality of the situation.

What are you talking about? The entire point of federal taxation is to decrease the money supply by taking it out of circulation.

HEY… Repealing DOMESTIC Tax will curb inflation even MORE!!!!

Not really… But if you’re going to be retarded about foreigner tax I can be just as retarded and make even more sense about citizens taxes.