Saving the Rainforest, One Pet Fish at a Time

Despite the objections of animal protection organizations, careful commercial fishing may be the best bet for the Amazon and the world's aquariums.

"Crocodile!" Célia Castro Pinheiro calls back to her husband as she steps into knee-deep water of the Rio Negro, a tea-colored river that begins in the Colombian mountains and flows into the Amazon below the Brazilian city of Manaus. Castro Pinheiro wades cautiously ahead, holding a machete high, worried less about carnivorous beasts and more about the condition of her fish trap, known as a fyke.

When she reaches the bag net structure, about 4 by 2 meters in size, she sees the wooden struts are broken and the net torn to shreds. This is bad news: Thousands of fish, several days' catch, have either escaped or been eaten by the crocodile.

"It was a young one," Castro Pinheiro says of the creature, with surprising composure, "no more than two meters long." Her husband, Jel Pereira da Silva, crouches on the riverbank, resting his rifle on his knees. "It's somewhere around here," he says, tapping his rifle. "Either we dismantle the trap and find another place or I'll stay here tonight, until the crocodile comes out of hiding."

The couple live in the state of Amazonas in northwestern Brazil, and their livelihood is threatened by more than hungry reptiles. Every day in the Rio Negro, they catch and sell fish that are later displayed in aquariums from New York to Berlin to Tokyo. According to estimates from Jens Crueger, president of the Association of the German Aquarium and Terrarium Associations, more than 100 million aquariums are maintained in living rooms around the world. By sheer numbers kept, ornamental fish are the world's most popular pets. The ornamental fish trade is estimated by the World Wildlife Fund to have a retail value of over $15 billion annually.

Most of the ornamental fish in pet stores come from breeding facilities. A smaller, though vital, proportion are wild catches from tropical rivers, delivered through the sweat and care of the likes of Castro Pinheiro and Pereira da Silva. Animal rights and conservation organizations don't like it when animals are caught in tropical waters and flown around the world so that people can relax at the sight of them. And some objectionable practices are sometimes associated with the trade. Some wild-caught fish, for example, are stunned with poison and then snatched. Unscrupulous middlemen often fail to care for fish appropriately. Sometimes they send the catch around the world crammed unsafely into plastic bags filled with water.

"If they do not perish from the damage they suffered during capture and transport, many animals die from diseases [as they are] weakened by constantly changing water conditions," writes the Tierschutzbund, an animal welfare association in Germany. That group asks ornamental fish fans to limit themselves to regionally bred species. The international animal protection organization PETA wants to end the practice of holding fish in aquariums entirely.

In many places, laws are being passed that make it more difficult to trade ornamental fish. In January 2021, Hawaii, one of the most important sources of ornamental marine fish, completely banned commercial ornamental fishing. India has banned trade, sale, and display of over 150 of the most common ornamental fish. A wide array of members of Parliament in Britain have called for a total ban on ornamental fish import. And direct person-to-person sale of live ornamental fish (which is, according to Crueger, a dominant trade channel) is banned on Facebook and Instagram.

If such activists succeed in seriously restricting this long-lived hobby, what will become of the people who make a living catching the fish? On the Rio Negro alone, 40,000 fishermen and women survive off this practice. There, at the beginning of the supply chain, you get a different view of ornamental fishing, one that recognizes how it can be good and sustainable for both human beings and the fish they hunt and keep.

Life on the River

On the Rio Negro, waves can surge as high as on the open sea. The river is so wide that you can't tell which direction the stream flows. At the edges, it merges into flood plain forests. From March to August, hundreds of square kilometers of rainforest are under water up to the treetops. At that time of year, the upper Rio Negro is the size of France.

Now, at the beginning of the year, river arms meander through the forest. At their edges, small sand islands sometimes rise out of the water. These are known as terra firme, solid earth. Masses of ornamental fish cavort near there. That's why Castro Pinheiro and Pereira da Silva set up their large trap at one such spot.

After the crocodile attack, they are busy repairing their fyke. Pereira da Silva cuts a branch with his machete until it is as sharp as a needle. Wrapping a fishing line around a plastic bottle, he climbs into the black water, wades up to the trap, and begins sewing the shredded net. Castro Pinheiro gets a small trap from the boat, puts it in the water, and places in it a pitted piranha head. She stirs a current with a small stick; seconds later, the first fish swim greedily toward the bait. "When they're full, they realize they're trapped."

In principle, catching ornamental fish on the Rio Negro is not that difficult: The fisherman has to know the right spots, but the rest almost takes care of itself. An estimated 4,000–8,000 species of fish live in the arms of the river around Barcelos, a large municipality in the Amazonas region. Most of them glitter and shine. According to one theory, that's because of the dark water: Fish recognize their reproductive partners by appearance, so evolutionarily the most striking have prevailed.

Pereira da Silva starts the outboard motor and steers the boat through the labyrinth of water and forest. Often branches hang so low that you have to lie down. It's about 11 a.m., and the sun is beginning to burn; time to bring home the morning's catch. Yellow-breasted macaws buzz in the sky, bats fly directly overhead, mosquitoes attack the boat's passengers. Everywhere around us, there's whistling and crunching, creaking and roaring. It's the sound of life on the Amazon, and those who fish are as much a part of it as the fish they cultivate.

Castro Pinheiro and Pereira da Silva live an hour away from the fish trap, on the shore of the village of Daracua, near Barcelos. They live on a disused boat. On deck, a tarp is stretched over wooden beams, and underneath they sleep in hammocks. The money they earn from fishing is enough for rice and beans, tools, gasoline, and medical treatment. Nature provides fish, meat, fruits, and vegetables.

Everyone in Daracua lives on one of these houseboats or in a simple wooden hut. Cooking is done in a communal kitchen in the open air. Around 50 people live in this village, all related by blood or marriage. Castro Pinheiro's father came across the then-uninhabited area now home to this village in the 1990s. It is located on higher ground, so it avoids the periodic floods. His whole family moved here. At first, they caught pirarucu and piranhas, for their own consumption and for sale.

Since the 1980s, tourists and sport fishermen from the United States, Japan, and Europe have increasingly come to the upper Rio Negro, attracted by the huge tucunaré cichlids that live there. Some of the fishermen were also aquarium owners, and were thrilled to see schools of neon tetras swimming past their boats. The demand for ornamental fish from the region increased enormously, and people from all over the state settled in Barcelos, with the ornamental fish trade creating jobs in fishing, commerce, and restaurants.

The booming city became the ornamental fishing capital of the world. Today, fish shops and billboards everywhere display fish from the Rio Negro. The telephone booths are shaped like discus fish. Every February the Barcelos area throws the Ornamental Fish Carnival, where the population splits up and goes at each other in fish costumes, neon tetras against discus.

Castro Pinheiro was 11 when she started catching ornamental fish. At 2 a.m., she and her father would slip out of the house carrying coffee and corn cakes, launch their canoe, and row off. They'd travel four or five hours, depending on where the spots with terra firme were. The practice has continued to shape her life and her family's.

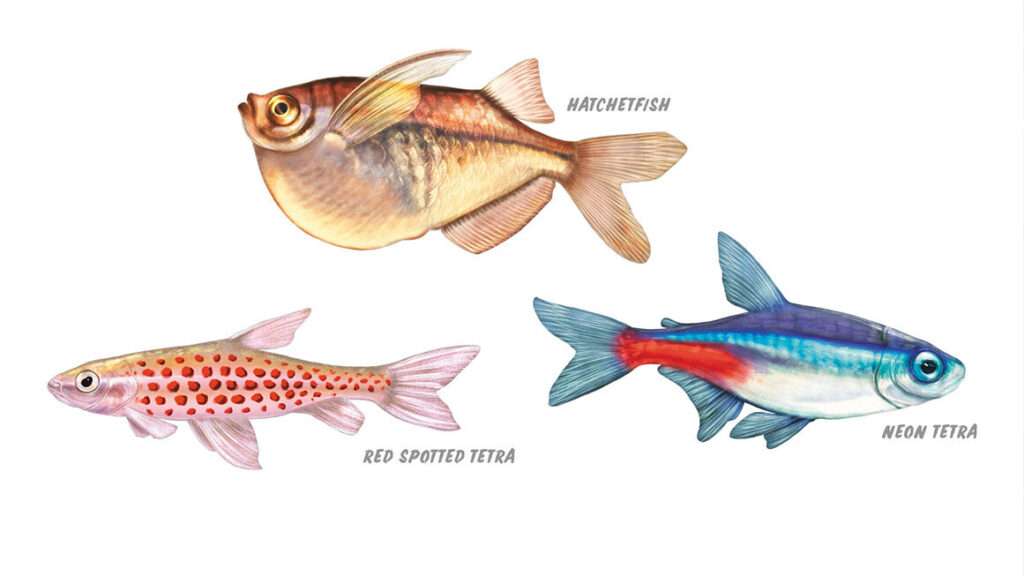

She and her husband catch an average of 10,000 fish a day. Now the couple are sorting them. Neon tetras, hatchetfish, red spotted tetras—in the large tub where the pair first collects the catch, the fish are hardly distinguishable at first glance. All are about the same length, glowing and circling in groups. She calmly and skillfully catapults the fish with her small net into white plastic boxes, separated by species.

The neon tetras are most abundant. The couple catches about 40,000 of them every week. They don't make money on all of them: Sometimes they don't sell at all, and sometimes they don't survive the journey to the customer. But this fish with the distinctive horizontal stripe is the most traded ornamental fish in the world. In the village of Daracua, 1,000 neon tetras cost 30 reals, around $6—slightly more than half a cent per fish.

Before the neon tetras end up in European, Asian, or North American aquariums, they pass through a trade chain with many links: two or three middlemen in Brazil, plus an importer in the destination country who spends roughly 50 cents per fish and sells them for roughly a dollar apiece. Then the fish moves through wholesalers and retailers on their way to the aquarium owner who pays $2 or more for each wild-caught neon tetra—more than 300 times what the fishermen get. "The traders do the business," says Castro Pinheiro. "We fishermen get almost nothing out of it."

Her twin sister, Mara, picks up the fish in Daracua, stores them in her home in Barcelos, then delivers them to steamers that take them to Manaus, the capital of Amazonas state. Mara married into a family that can afford a house big enough for a couple of aquariums. That qualifies her to be an ornamental fish middleman. "She doesn't earn much either," says Castro Pinheiro. "The big money is made by people in Manaus or São Paulo." She means the exporters who know how to store tens of thousands of fish without killing them and also know the global market and have contacts with importers all over the world.

The Global Fish Trade

The 21st century has seen upheavals in the international ornamental fish market, including the mysterious departure from the field of its biggest operator, a man named Asher Benzaken. Back in the day, 90 percent of the Amazon basin's trade in such fish ran through Benzaken. None of the other 13 export companies were able to fill the gap after he left.

In particular, the demand for neon tetras could no longer be met. So aquarium operators outside Brazil, especially in the Czech Republic and Indonesia, began to breed the popular species on a large scale. Farmed fish are considered less beautiful, they have less genetic diversity, and they are more expensive. But the supply is reliable, which has become increasingly important in such countries as Germany, France, and Britain.

Twenty years ago, hobby aquarists in these countries still bought from owner-operated pet shops. Fish could be ordered there, and each dealer had his or her own favorites and connections. Specialists could be found for fresh water, for Southeast Asia, for catfish. But today the market is dominated by specialty retail chains such as Fressnapf in Germany, Pets at Home in Britain, Maxi Zoo in France, and the pet departments of large hardware stores. The chains want to have the same assortment in every store at every time of the year, and they therefore demand fewer species in larger quantities. When suppliers from the Amazon could not meet this need, the region lost market share. Today, the volume of business in the part of the world where Castro Pinheiro and Pereira da Silva fish is about half of what it was in Benzaken's time.

Long transport routes, poorly paid fishermen, declining demand—wild ornamental fishing around the Amazon seems to have nothing going for it. But Joely-Anna Mota sees things differently from her garden in Manaus, in a gated community outside the city center.

Mota, a hearty woman in her mid-40s, is an expert in fish tourism around the Rio Negro, formerly with the Manaus-based Universidade Nilton Lins. She knows animal welfare organizations are against ornamental fishing in this area, yet she sees this industry as offering important opportunities—not just for the fishermen, but for nature as well. "It can become a very clean and fair business and, moreover, protect the rainforest," she says.

Mota grew up in Carauari, a community on the upper reaches of the Rio Juruá, in the middle of the rainforest. The people there traditionally lived from extractivismo—using nature for one's livelihood, a right protected by law in Brazil. This includes self-sufficiency and trade in acai berries, Brazil nuts, resin, coconut oil, and ornamental fish. In order not to endanger the basis of their existence, Mota says, people living off the land in this region tend to treat nature with respect.

Today, alluvial areas are being drained in many parts of the Amazon rainforest, and soy and cattle are the country's most important exports; trade in tropical timber and gold prospecting are also significant. A fifth of the rainforest has been cleared for those industries over the past 40 years. "The ornamental fish trade can mitigate this dramatic development," Mota argues—if more of the economy of the Amazon basin comes to rely on it.

In the late 1980s, the Taiwanese biologist Ning Labbish Chao studied the consequences of this industry. His study, which was published by the National Institute of Amazonian Research, showed not only that ornamental fishing is a cornerstone of people's livelihoods in the upper Rio Negro, but also that it is sustainable. He had expected to find fish stocks declining sharply in the fished area. But measurements over several years showed they in fact remained constant. In the dry season, many schools of fish from the Rio Negro are trapped in small puddles of water. Many fish starve to death or are eaten by a natural enemy. "Only a vanishingly small portion of the population survives the dry season," Mota says. With this huge natural blow to fish populations, ornamental fishing turns out to be largely irrelevant to the stocks.

Chao founded an initiative in 1991 to promote ornamental fishing, called Project Piaba. Its slogan: "Buy a Fish, Save a Tree." It is supported by several partners, including the National Institute of Amazonian Research, the World Wildlife Fund, the World Pet Association, the World Food Programme, and the International Ornamental Aquatic Trade Association.

Mota has been one of the project coordinators since 2014. With her colleagues, she works on enhancing the value of wild-caught fish from the region. "In the past," she says, "people emphasized quantity. They wanted as much as possible for their money." Today, people buy stories—they want to know about the origin of the product and the producers, and they appreciate the handmade.

That's why Project Piaba developed a seal with the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food Supply for the neon tetra from the Rio Negro—one with a designation of origin, similar to that for Parma ham or Champagne. In addition, fishermen, middlemen, and Project Piaba coordinators are now united in a cooperative, and the distribution channel from the villages to exporters is certified. Crueger, the president of the Association of the German Aquarium and Terrarium Associations, thinks it's a good idea. "We support such certification." He and his European peers, he says, are willing to pay more if they can be assured that social and environmental standards are being met.

'Both Are Good for Us'

The sun is rising in Daracua. Castro Pinheiro and Pereira da Silva have been out on the Rio Negro for hours. In the pile hut next to their houseboat, Romualdo Rodrigues heaves himself out of his hammock. At 56, he is the oldest ornamental fisherman in Daracua. An athletic-looking man with rough hands and leathery skin, he loads up for a tour in his narrow, motorized wooden canoe and shortly thereafter steers into one of the river arms, repeatedly scooping the overflowing water from the footwell of the canoe with a plastic bottle.

After 20 minutes, he switches off the engine and steers into a small waterway. A dead forest suddenly appears, countless charred trees jutting out of the river, as black as the water. "That was a ribeirinho" who set the fire, Romualdo says: a person who lives on the riverbank. In the dry season, he wanted to clear the land to use it for agriculture. "But once there's a fire here, nobody puts it out." The fire burned for days. "That's the danger," says Romualdo. "If you don't have a job, you have to do something to survive."

Then he brings up another industry that has expanded in recent years. Along the villages on the Rio Negro runs the main cocaine trafficking route, Romualdo says, downriver from Peru and Colombia to Manaus and from there to the rest of the world. "Every ribeirinho who can't make a living from extractivismo tries his luck in another way." The fisherman cranks up the engine. His is a way of life that, if more widely accepted by those concerned with conservation, could provide different, better ways for people in the basin to survive.

In the early evening, he retreats to his hut while Célia Castro Pinheiro dangles her feet on the houseboat. Her husband, as always at this time, goes bait fishing in the water. As he emerges, his cellphone beeps on the boat deck. He reaches for it, still dripping wet. He nods, types, tells his wife that tomorrow she has to go fishing alone. He has an assignment in Barcelos. Sport fishermen from southern Brazil are looking for a guide.

Sport fishing is still good business on the Rio Negro: Many ornamental fishermen work on the side for tourists hunting for the giant tucunaré, who then take a selfie and throw the fish back into the water. "Some buy our fish for their aquariums," Castro Pinheiro says. "Others catch them for a photo." She shrugs. "Both are good for us."

Show Comments (34)