Banning 'Unconscionable Excessive' Gas Prices Is Risky Economic Nonsense

Democrats are trying to inject a political solution into an economic problem.

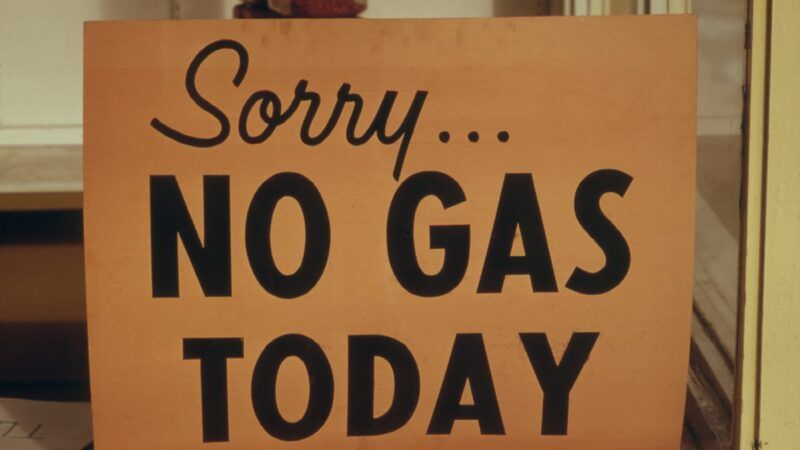

Having failed to learn from history, Congress is apparently determined to force Americans to repeat it.

Earlier this week, the House of Representatives passed a bill granting President Joe Biden, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and state attorneys wide-ranging and ill-defined powers to crack down on "unconscionably excessive" gas prices, supposedly in the name of protecting consumers.

What counts as "unconscionably excessive," you might be wondering? That's in the eye of the beholder apparently, as the Consumer Fuel Price Gouging Prevention Act contains no explanation or definition to limit the new executive powers over prices at the pump. Any seller deemed to be "exploiting the circumstances related to an energy emergency" can be targeted with civil penalties or forced to stop selling gasoline at whatever price the authorities have deemed to be excessive. The text of the bill allows the FTC to determine appropriate "benchmarks" for deciding whether some gas prices might be grossly excessive—a neat little trick that effectively allows the FTC to set prices if it chooses to do so.

Of course, price controls, even when enacted in roundabout ways, don't work. History is full of examples demonstrating this basic economic fact, but probably the most on-point example is the gasoline price controls enacted by the federal government in 1971. "The results were disastrous," Jack Rafuse, a Nixon administration energy advisor, wrote in the Chicago Tribune in 2007. "Oil exploration and domestic oil production slowed sharply. And foreign oil poured into the nation's gas tanks, filling the booming demand for price-controlled gas."

When you mess with prices, they tend to mess back. Artificially low prices signaled to consumers that they should keep filling up, but gasoline supplies couldn't keep up. Long lines and rationing were the predictable results.

No one wants to pay more than $4.50 for a gallon of gas—that's the national average right now, meaning many places are seeing even higher prices—but severing the ability of higher prices to signal to consumers that they should buy less is no solution. At best, it merely hides the problem and creates new ones.

Expanding the executive branch's power to crack down on businesses that are merely responding to market conditions is no solution either. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce warns that the legislation will allow the FTC "to make supply and demand mandates for the energy sector," potentially resulting in falling domestic energy production and higher gas prices.

In other words, the 1970s all over again.

Even some Democrats who ultimately supported the bill—which passed Wednesday with a near-party-line vote in the House—seemed to recognize the danger.

Rep. Paul Tonko (D–N.Y.) told E&E News, a trade publication focused on energy and environmental issues, that the bill was "injecting a political solution into an economic problem."

That's exactly right. For months, Democrats have been trying to scapegoat rising prices throughout the economy on supposed price gouging. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) memorably and bizarrely claimed that higher prices at grocery stores were the result of greedy capitalists, despite the fact that grocery stores operate on some of the thinnest margins of any business thanks to robust competition. Warren and some of her Senate colleagues have introduced a separate bill to give the FTC similar powers over price gouging in all parts of the economy. That bill uses the same vague "unconscionably excessive" framing as the just-passed gas price control bill in the House.

These attempts to deflect blame for the highest inflation rates in 40 years are "dangerous misguided nonsense," according to none other than Jason Furman, one of the Obama administration's top economic advisors.

"The problem with this narrative is that it's just a pejorative tautology," wrote The Washington Post's Catherine Rampell about Warren's bill. "Yes, prices are going up because companies are raising prices. Okay. This is the economic equivalent of saying 'It's raining because water is falling from the sky.'"

To carry that analogy one step further, the bill passed by House Democrats this week might best be understood as an attempt to hack the weather app on your phone to assure you that there's no rain falling now and no chance of rain falling later in the day. Seeing that might make you feel good, but you'll be ill-prepared to deal with the weather when you step outside.

Price controls are lies—pleasant ones, perhaps, but lies just the same—and the government ought not to be in the business of forcing businesses to lie to consumers for political reasons.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

It's easy to tell "unconscionably excessive" gas prices.

Those are the ones no one will pay.

Can we gat an amen for forming an "excessively fascist government" control board?

Easily work do it for everyone from home in part time and I have received 21K$ in last 4 weeks by easily online work from home. (rea20) I am a full time student and do in part time work from home. I work daily easily 4 hours a day in my spare time.

Details on this website >>>> https://brilliantfuture01.blogspot.com/

To everyone who fell for the Trump/Russia collusion Clinton cabal criminal conspiracy, may I mention to you what a damn idiot you are? An idiot who sat in front of the pages of WaPo, NYT, or the screen with Rachel "bombshell" Madcow and lusted after every word she "uddered". Don't you feel stupid now? With Clinton made up bullshit that was obviously bullshit you fell for it. Or, maybe you don't feel stupid and you still believe the ridiculous lie that was put upon this nation for four-plus years. If so, please stay far, far away from a voting booth in the future. You are too stupid to vote! Look at what your stupidity as done to this nation. For shame! You personally should be sending letters (handwritten) to Mar-a-Lago, requesting Trump return to the White House.

How could so many supposedly educated people be so damn stupid to deliberately vote to undo what good times we had only 18 months ago.

And, what's so sad is most who vilified Trump on this site are attorneys! How bad is that for our nation? Crooked, stupid lawyers! Millstones and oceans are the best you deserve!

Because Trump disliked government price manipulation?

Want to create a website or android app for your bussiness. We are a company with 8 years of experience we have our headquarters located in Kolkata,India.We are specialized in app development and web development our clients are from worldwide. You can simply visit our website and check our portfolio.

Will it help me pay for my gas?

How about an ‘amen’ for an organization that hunts down and cleanses leftists from the US?

They also just introduced a bill in the Senate to require a federal firearms license to buy or own a gun:

https://notthebee.com/article/senate-democrats-apparently-thought-they-werent-going-to-lose-hard-enough-in-november-so-they-just-introduced-a--nationwide-highly-restrictive-gun-control-proposal

That will stop all those criminals!

The idea is, given that street thugs and gangbangers will not follow this law, it gives the feds more power to put them away.

It does not mean they will actually use this power, though.

I just don't see what authority they have to do something like this, even if it could pass.

Also, remember how backed up the passport office was for - I dunno - forever? Or the immigration bureaucracy? Or the VA? Or any number of other federal agencies people have the misfortune of having to deal with personally?

Can you imagine, if something like this bill were put into effect, and you, as a legal gun owner, all federally permitted up and everything, come up to your five-year-renewal date and submit your paperwork and they're backed up? Or whatever future administration decides as a policy to slow down their processing? Or maybe the people doing the processing are just as efficient, professional and diligent as other federal employees. Now you're expired. You can't legally own a gun. You can't sell it either.

Actually, unfortunately, this is one power I do believe the feds explicitly have. It's regulating the militia, the claim will be that the feds need to know who actually has what arms in order to make the militia a useful force.

It would actually make sense if they were desiring to enable a modern-day functioning militia. Unfortunately, I don't believe the use of a power has to be for the reason used t explain it. The power is given to Congress, it is up to Congress to decide how to use it so long as they stay within other constitutional strictures.

If I remember correctly, if you have an FFL you can legally build a machine gun.

Can anyone confirm that?

ifif youyou fifile the right paperwork

If you build machine guns for police/military use, you can get the right FFL to do so.

That is a common misreading of the 2A using modern definitions for common colloquialisms of the 1700's. You have to translate it a bit to get a more modern reading. My modern paraphrasing would read something like the following:

"Because the government will need a professional, well-equipped military, therefore, the government will not be allowed to disarm the public."

Remember, the people who wrote these words had just recently fought a war against their former government, which had tried to disarm them. That's also why we have the 3rd Amendment - No one ever worries about the feds posting soldiers in your house these days, but they had just been through that.

The enumerated power over the militia is laid out in Article 1, Section 8, which says:

"To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress;"

In this case, the Militia is comprised of both professional soldiers, state-run volunteer 'militias' (National Guard), and volunteers if and when needed. And the feds are supposed to be supplying them with weapons, not 'permitting' them weapons.

Militia's were run by the states, not the Federal Government.

democrats are the best gun salesmen ever

Who is going to bell that cat? Can't wait to see the volunteers. I dare a pink or purple-haired soy boy to come down my drive with intentions to make ME comply with their regulations. Or, maybe the soy-boy will send her wife to do it.

Meanwhile the so-called "smart" attorneys, both practicing and in academia, have decided that they can't speak up to support the Constitution. Because those lawyers know their firm can be destroyed overnight by the twitter crowd and the professors know that tenure no longer means anything. The little monsters they have created can toss them out of their cushy Chaired position without a second thought. LOLOLOL. Sucks to be you now, doesn't it?

It never fails to amaze me how the socialists infiltrate the colleges, without remembering who is the second group up against the wall when the revolution is over.

Another in a growing list of justifications organize and remove all democrats. The assholes better pray they lose big in November.

Democrats want Venezuelas economic policies without wanting Venezuela. Evil or stupid?

It can be both.

Can I get the Venezuela without the Venezuelan economics? Arepas are pretty tasty.

An oven knows no nationality.

Corn doesn't care who harvests it.

Stupid is thinking sales prices are sellers' dictates.

Evil is threatening armed attack against people for making peaceful offers.

have you learned from your research to stop supporting (D)?

Hey democrats (and some GOP) have said deficits don't matter. Let the government give everyone an electric car. Sure the power system can't handle it but we solved the gas problem.

Is there anyone more out of touch with economics then Warren, Sanders and AOC, the 3 genius of the democratic party.

Nixon. 1972. Gas lines. Odd and even license plates.

I just can't wait.

I think that was J Carter in 76 or 77.

I lived it. Just got my license when it began.

guys, guys! you're both correct.

I was an even. Thanks

You are both wrong - it was 1973. I was living in NY state and had to fill up on even numbered days which meant I could not drive home on an odd-numbered day (450 miles).

This will be a dozen times worse.

Compare and contrast:

"[High gas prices] are not an enemy of action, it's an ally of action."

Remember that quote when you vote for "wrong within normal parameters".

Send some of that 4 dollar gasoline to California, please. It's 6.19 here.

Al Gore lays down green challenge to America

Zachary Coile

Chronicle Washington Bureau

July 18, 2008

I have a green challenge for the democrats. They can improve carbon emissions by committing suicide en masse.

Just beat the shit out of some democrat and take theirs. Should be cool with them, they love reparations and redistribution of wealth.

We do have to drastically reduce fossil fuel use in this century. Do you have a plan?

Last thing in the world we 'need' to do is reduce fossil fuel use. It is very much the lifeblood of the world, and there is no substitute.

True. When it gets cold and you need to turn on the heat in your house do you go with electric heat? Or some form of gas or oil?

Hmmmm...

"We do have to drastically reduce fossil fuel use in this century."

Assertions from lefty shits =/= evidence nor argument.

Eat shit and die.

I have a plan. You kill as many of your fellow democrats as possible. Then when you can’t get to any more of them, kill your self. That will help.

Does that answer your question?

Jay Inslee is a Marxist traitor guilty of a myriad of capital offenses, including the murder of thousands of elderly nursing home patients similar to Cuomo’s mass murders.

Sadly we can't seem to get rid of King Jay.

Chaining his limbs up to four full size pickups and then hitting the gas would seem appropriate.

Looking more like Carter all the time. Only we're funding a proxy war against Russia in Ukraine instead of Afghanistan.

Only we're funding a proxy war against Russia in Ukraine instead of Afghanistan.

Yeah, but without the intelligence, panache and cleverness of the covert Afghanistan conflict.

Does this mean in 50 years we'll finally be packing up the last troops deployed in a two-decade long nation building exercise in Ukraine?

children born in Ukraine will be raised to hate the Great Satan and become terrorists

Yep, POTUS Biden is the Second Coming of Jimmy Carter. Only way more inept and way more venal.

Yeah, Carter was the wrong guy at the wrong time, but I'd never accuse him of being dishonest or inherently corrupt.

I call him Joey Carter sometimes.

At this point, Carter is a favorable comparison. Biden is now the bar for shitshow presidents.

Not Woody Wilson or FDR? Biden hasn't rounded up tens of thousands of people based on race or segregated the civil service or passed a sedition act. He is headed in that direction, however, and if the Ministry of Truth is resurrected he will be in their company.

Give him time. Biden hasn’t even been in office for a year and a half yet. Yet look at all he’s accomplished. Imagine how bad it will be if his regime is allowed to exist for another 2 1/2 years.

High gas prices, high inflation, rising crime , it is the 70's, with worse music.

only the King Biscuit Flower Hour can save us now

"Democrats are trying to inject a political solution into an economic problem."

New here?

I would like democrats to all have an injection. A lethal one.

ALL politicians who write coercive laws believe coercive politics trump economics, rights, reason, choice.

Democracy is collective rule over individual rights, by giving reps all the power. That creates a nobility who exploit the public. The public pretend not to notice, blaming various groups, instead of looking in mirror and asking: "Who will protect me from my protectors?"

For vote buyers, all problems have political solutions. if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

P. J. O'Rourke said it best, as always: "When politicians control how things are bought and sold, the first thing to be bought will be politicians." I'd like to have been a fly on the wall when they were planning this bill. After failing to be FDR with their policy ambitions, are thy now aiming for Nixon and Carter?

Too bad PJ backed Biden before he died.

And Hillary.

Yeah, that was pretty pathetic.

In his defense, when all candidates are antimarket Democrats, selection criteria become less interesting.

Yeah absolutely, we must permit monopolies and collusion among sellers dominating markets.

Eat shit and die, lefty asshole.

The bill doesn’t threaten police action against people for collusion and suppression of competition. Those bills were passed ages ago.

This bill threatens police action against people for striving to offer something that others increasingly desperately need. It is a bill meant to attack both benefactors--for daring to acquire an increasingly scarce commodity, and the desparate--by denying them legal access at any price.

Mere gasoline? Baby formula, baby!

Those silly commies, so predictable.

"...congress is determined to force..."! That "force" creates a master and slave, a ruler/ruled society, an unfree country.

Humanity's biggest asset is individuals who are free to innovate, e.g., free from coercive politics, free to make choices without interference from others, however "well intended". I contend "good intentions" are no excuse, no justification, for controlling peaceful others. People who want to "live & let live" have a right to life, liberty, property, business, happiness. This is called, political equality, individual sovereignty, the opposite of a sovereign ruler or sovereign representation. A sovereign citizen cannot co-exist with others who believe they are "more sovereign", "more equal", or "authorities with special privileges". For example, people who have solutions for their needs may be prohibited from fulfilling those needs due to govt. intervention, e.g., monopoly "services", i.e., services forced on those who don't want/need them. Law often protects exploitation, prevents freedom of economic action, without justification, immorally, as if the politic of "the law is the law" is a magic chant that could explain/justify a wrong. It can't/doesn't, and no one should ever let that lie stand in their way. We have a right to live and let live. It follows, natural assets are useless without economic freedom. Life as a free person is unlivable in the authoritarian state, the present situation worldwide, the unfree world.

No one should be allowed to take any government office - elected, appointed or civil service - until the pass Econ 101 and Intro to Physics. These people a simply morons.

AOC actually has an Econ degree, which is shocking, I know, but I doubt that she could pass freshman-level Physics.

We actually had a class at my University called 'Physics for Poets'. None of those pesky math equations or physics lab experiments, just broad-based concepts, like what people mean when they use a word like 'momentum' or 'velocity'. Etc. Maybe she could try that.

Her Econ degree is like that “physics for poets” course. Real Econ is mathematical modeling based on solutions to a series of differential equations designed to model real-world behavior. But you can’t teach this to undergraduates who have had less than four years of advanced calculus. So, they teach IS-LM, which is a flawed model and has been discredited since the 60s, but at least gives people a dumbed down version of economic modeling to study.

Ironically, ISLM fails because of the flawed assumption that government stimulus packages (“helicopter drops”) are spent immediately because the recipients assume the checks are permanent. The Lucas Critique undercut this model by predicting people will save stimulus checks because they don’t know when the next one is coming along. It was right in the 1970s and right again in the 2020s…..

I saved my stimulus until I needed a new transmission. Then it evened out.

My upstairs, unemployed neighbor bought a bunch of cool gadgets and fancy cuts of meat to grill. He's on rental assistance still. Kickass drone, though.

Right there is a mini-lesson on why some poor people stay poor.

I'd argue the opposite - that only poor economists bring in complex math to replace straightforward logic. Some of the most important concepts in economics (supply and demand, comparative advantage) were formulated in simple words, without the need for fancy curves and modeling. Complex math is mental masturbation and only serves the purpose of justifying one's work in the context of publishing useless papers in academia. Since there are so many factors governing every human's individual decisions, it's impossible to make any worthwhile mathematical models in economics, one can only loosely predict aggregate trends, and simple arithmetic works fine for that.

They would pass. And it wouldn't make any difference. Their bread is buttered on the side with voters--in all their incentivized ignorance. That's all that matters.

A Constitution protecting the innocent against malicious state actors does occasionally help, if someone can afford the cost of challenge, but usually is a powerless sieve against a rationally ignorant mass of voters.

The fundamental "risky economic nonsense" is coercive (authoritarian) politics. Free enterprise can't exist in an unfree country. Politicians call slavery "freedom" and fascism "capitalism", so they can blame the misery they create on others. Others pretend they are free, in an unfree world, and support the politicians. So, whose fault is it? Why do people self-enslave?

"Why do people self-enslave?"

Because state democracy usually permits no better alternative.

"Why do people self-enslave?"

Because they are not libertarians, and fall closer to the "perceived safety" extreme of the "freedom vs perceived safety" spectrum.

Please make sure your kids’ schools teach the rudiments of supply and demand and competition.

that would exclude attendance at any government school

The high price of gas is because of a rigged market orchestrated by political pressure. It started in April 2020 when gas was $1.89 a gallon and the oil companies pressured Trump to force Saudi Arabia and Russia (25% of world oil output) to cut production in half to hike prices. Trump threatened to cut off military support for SA (political pressure). SA and Russia cut production and prices started to rise, about 30% by the time Trump left office. They have continued to rise and were exacerbated by the invasion of Ukraine. It was politics by the US oil companies, then Trump, then the Crown Prince, the Putin, to cut production and hike prices. The goal was economic (more profits for oil companies), the means were political (pressure and threats).

So to use politics to undo this fixing of the market is appropriate since it was politics that has caused the high prices.

And what is unconscionable prices: I will illustrate......

The price of oil was $141.71 per barrel in June 2008 while gas cost $4.10 per gallon on average. In March 2022, the post said oil cost $99.76 per barrel, while the average price of gas was $4.32 per gallon."

The price of a barrel of oil may be a significant factor in the price of gas, but it is not the only factor.

"And what is unconscionable prices: I will illustrate......"

This is what lying piles of lefty shit assume constitutes "argument", which is the reason they should be ignored.

Est shit and die, asshole.

The price of oil was $141.71 per barrel in June 2008 while gas cost $4.10 per gallon on average. In March 2022, the post said oil cost $99.76 per barrel, while the average price of gas was $4.32 per gallon."

----------

Oil price is only one factor in gas prices. When you have to pay more to refine or ship the oil, prices go up. When wages go up, prices go up. Etc etc etc

*citation needed

Seems lefty shit didn't have a lot of data.

Lefty shit should fuck off and die.

Not you, RtD,.

Price fixing doesn’t solve the scenario you describe. It only makes consumers suffer even more.

Prices are a measure of market scarcity. Decoupling a reality from its measurement only leads to mistakes, frustration, and waste. If high prices in some sense are are a "problem", the only solution is some combination of demand decrease and supply increase. Price fixing instead simultaneously increases demand and decreases supply.

But even Congressional Democrats are well are of this oft and even recently observed consistent old historical fact of economics. But political incentives are such that deliberately making a problem worse is frequently an acceptable cost of admission.

It's hard to recall that only 18 months ago we had $2.00 a gallon gas, no new wars, low prices and rising wages.

For everyone that voted for Joe Biden, may I say to you a big......

F.U.!

Unrealized counterfactuals breed confidence.

Everyone would do well to remember that Trump's and Biden's economics differed little in quantity and nothing in quality. The electorate has spoken, and it wants a centrally planned train wreck, regardless of team affilliation.

We are yet again in a period of broad bipartisan market suspicion, triggered, as usual, primarily by the mistakes of central planners. And the suspicious demand more action by those same planners.

Hopefully it ends more like 1983, and not 1945.

"Unrealized counterfactuals"

What was counterfactual? Gas was about $2, no wars had been started, inflation was low (price increases were slow), and wages were rising with inflation.

English. Learn it. Use it properly.

For everyone. Remember the racist Trump improved the economic condition of every citizen, regardless of race, creed, or color.

Now take a look at the racial breakdowns for the fascist economy.

And the *ONLY* significant difference is who was PotUS.

Got it.

“The problem with this narrative is that it's just a pejorative tautology," wrote The Washington Post's Catherine Rampell about Warren's bill. "Yes, prices are going up because companies are raising prices. Okay. This is the economic equivalent of saying 'It's raining because water is falling from the sky.'"

For Liz, if it is raining, it is because those evil corporations are pissing on you.

lmao.... "an energy emergency"...

Every non-moron saw that coming a thousand miles away... It was titled, The "Green Energy" initiative which was nothing but a copy-cat initiative of the Tree-Huggers which stole all the land for communism (38% of the USA).

How stupid do these politicians think people are? Their narcissistic gov-gun packing doesn't fool normal people. They're literally robbing the USA and empowering a Nazi-Regime.

Technically, in order to be "risky", something has to have at least some chance of not going wrong. Jumping off the roof of my house would be "risky", because if I landed just right, I wouldn't injure myself. Jumping out of a plane without a parachute, OTOH, would not qualify as risky, because I'd have no chance of survival. It would merely be suicidal.

This isn't a risky policy, it has a 100% chance of going wrong.

Keeping in mind that they WANT high energy prices, the shortages that would result wouldn't even technically be the policy "going wrong"; This more like somebody pushes you out of the plane without a parachute, intending that you end up dead. The harm isn't just certain, it's intended.

What better to convince people to buy electric cars than gas shortages!

As long as no one asks where the electricity to charge the battery comes from. A carbon based power plant no doubt.

The law they should pass would require an electric car owner to buy a windmill and or solar roof to charge the car, and never, ever, allow them to hook up the grid.

(plus a per mile charge equivalent to the gas tax for road maintenance)

The reason for all of this inflationary value is the implementation of minimum wages by states and cities. Up until people "gave themselves raises" the federal government controlled inflation through minimum wage and interest rates. The moment that states and cities doubled the minimum wages they created 100% inflation.

Unintended consequence is a higher wages at every level and higher tax bracket for 100% of the active wage earners, and loss of needed income by those retired without government pensions.

The issue is that a federally controlled minimum wage held inflation in check. Does anyone really believe that giving a 100% wage increase will not cause 100% inflation plus higher taxes? If so they are fooling themselves.

Passing higher minimum wage laws was actually theft of income from companies. They had to make 100% more on the wages side in order to break even. They have to give raises to those in higher brackets to make up the difference as well.

It is IMPOSSIBLE for the people to use the ballot to take money from someone else and not have unintended consequence. Currently, even rent is moving to 100% increase in almost every city. Thank you liberals for attempting to steal by vote. You caused this.

The Democrats want to force down living standards, creating a generally poorer society. End single family homes in favor of dense, rent controlled apartments. Get you out of your cars unless you’re wealth enough to afford a Tesla. Etc. etc. However, they know they need to slow boil the proverbial frog. High fuel prices are something they favor, but rapid price increases immediately hit everyone’s wallets and everyone begins to see what they are doing. So, they cry crocodile tears and demand price controls - perhaps bringing prices down from over $6 per gallon to over $5 per gallon, and then they say look at what a favor they’ve done for you. Never mind that it wasn’t that long ago that fuel prices were half that amount. That the controls will lead to further shortages and price increases isn’t this month’s problem.

I will say though, you’ve got to hand it to the Dems. In states where they hold power they are making people poorer.

"Democrats are trying to inject a political solution into an economic problem."

Now that's a surprise. That's what they do for everything! Inject politics into the issue.

Again? First Nixon's wage & price controls, then Jimmeh's "Moral Equivalent of War" charging taxpayers for the Federal Energy Department plus windfall profits tax, and now this... What else is "new" in The Kleptocracy?

When rational people looked into Warren's claims to be Cherokee it was quickly found to be a complete delusion on her part. So now she thinks she's an economist...

That the blonde blue-eyed Warren thought she was Cherokee suggests a lack of familiarity with mirrors.

Her mother was a liar, obv.

Very good point; she need to declare herself a fucking lefty ignoramus.

In an attempt to transfer such a foolish task to an even more incompetent arm of government, Biden, the DO NOTHING, INCOMPETENT, SELF-SERVING Congress votes for a wishy,washy bill for a task that demonstrates their UTTER IGNORANCE. The price of Oil & Gas is driven by the worldwide market, not an individual oil company!

Making Biden President Was Risky Economic Nonsense... and the USA has been the loser so far.

It may be past time to change the process by which laws are made. Instead of going from Congress to the White House, bills should have to pass through SCOTUS for constitutional review before going on to the White House for the President's signature. If SCOTUS says the bill is unconstitutional, it goes back to Congress for revision and SCOTUS looks it over again.

If CA gun laws required even an appellate court review prior to being signed into law by the gov, a lot of taxpayer money wouldn't be wasted finding them unconstitutional

If ca were nuked, it'd save a lot more, im sure.

Orlando shooting, first time in history a "terrorist" hit the right target. Highly suspicious.

Dont get me wrong. I intensely hate the demonicrats and other catholic namblanese franchises. But facts are, gasoline consumption has some pretty serious polution issues. On top of that, its a form of energy who's controllers have not been interested in expanding renewable energy sources. Extra to all that, it cant be imagined that gas consumption isnt having a serious tectonic impact besides atmospheric impacts. To frame any attack at such an intransigent energy monopoly as that as purely politically motivated is foolishness and political spinnery in and of itself. I'd hope that libertarianism was about reason and logic as opposed to bias appeasement.

And to double down, scumbocrats are the slime of the world.

Their slime is too often starting to ooze onto marginal parties as i turn up the heat.

The climate nuts are against nuclear energy, so they are not to be taken seriously. Without nuclear, it’s going to be a very long time before there is an alternative that will provide enough energy without destroying our economy.

"...But facts are, gasoline consumption has some pretty serious polution issues. On top of that, its a form of energy who's controllers have not been interested in expanding renewable energy sources. Extra to all that, it cant be imagined that gas consumption isnt having a serious tectonic impact besides atmospheric impacts..."

Watermelon assertions =/= "facts".

Only if we were not so car dependent and built walkable cities?

You'd have to change zoning rules in thousands of jurisdictions, unfortunately.