Florida, Tennessee Ban Ranked-Choice Voting Despite Citizen Support

Politicians who benefit from divisive election politics resist reforms that threaten the status quo.

On Monday, Republican Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a massive election bill into law that creates a special squad to investigate election fraud and crimes and increases some criminal penalties for some election-related violations.

But that's not all. Buried on page 25 of the 47-page bill is a complete ban on the use of ranked-choice voting anywhere in the state, regardless of what voters might want. In this case, it's the voters of Sarasota, who overwhelmingly decided in 2007 (with 77 percent in favor) to switch to this type of voting for local elections.

A similar ban was passed in February in Tennessee. There the target was the city of Memphis, where voters first decided they wanted ranked-choice voting back in 2008. The City Council itself resisted the change and attempted to get voters to repeal the system in 2018, but voters instead still chose to keep ranked-choice by 62 percent. Nevertheless, S.B. 1820 will stop Memphis (and any other municipality or county in Tennessee) from using ranked-choice voting to determine election results.

In Tennessee, the bill's sponsor, state Sen. Brian Kelsey (R–Germantown), made a typical claim by ranked-choice opponents—that it's a "very confusing and complex process that leads to lack of confidence." This is belied by the fact that voters keep choosing it when given the option to do so.

There's a lesson here on how some of the resistance to certain election reforms is actually about entrenched political interests protecting themselves from electoral consequences.

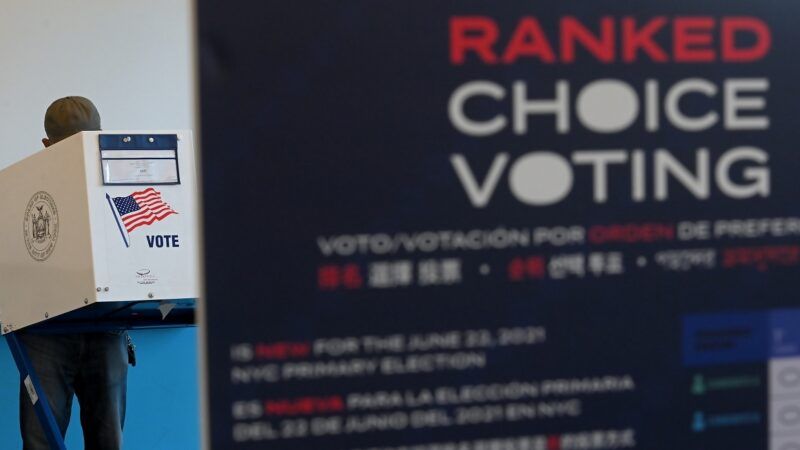

Ranked-choice voting is a system where voters don't just choose a single candidate over the others. Instead, voters are invited to rank candidates by preference. In a slate of five candidates, a voter can choose a favorite, then rank the rest as a second-choice, third-choice, et cetera.

When votes in this system are tabulated, a single candidate must receive a majority of the vote, not just the most votes, in order to win. If a single candidate doesn't surpass the 50 percent threshold, the candidate receiving the least number of votes is disqualified. Then the votes are retallied. For those who chose that last-place candidate as their first pick, instead their second choice is now their vote. The process repeats until a single candidate gets the most votes.

One of the stated goals for proponents of ranked-choice voting is to avoid a situation where, due to the size of the candidate pool, a person is declared a winner with just 30 percent of the vote or even less. Under the status quo, a candidate with polarizing positions that appeal to a small but committed group of voters can overcome the majority if votes get split among three, four, or more candidates.

Ranked-choice voting therefore also creates a system where third-party and independent candidates can have impact without voters having to worry about allegedly "throwing their vote away" or choosing a so-called "spoiler" who can't win but can draw votes away from a similar candidate. A voter can select a Libertarian Party or Green Party candidate or an independent candidate as their first choice. Then, the voter can select a more conventional Democrat or Republican candidate as the second choice, knowing that they can have their values reflected in initial results without losing their voice entirely.

FairVote, a nonpartisan organization pushing for election reforms, sees ranked-choice voting as a boon for voter participation and support of election outcomes. It views ranked-choice voting as a way of countering increasing polarization among both Democratic and Republican candidates: "America's constitutional system of governance is based on compromise. When polarization causes that to break down, policymaking can grind to a halt or swing wildly based on which party has majority control."

Unsurprisingly, politicians who benefit from a highly polarized environment wouldn't want an election system that encourages alternatives. Florida's politics these days can most certainly be described as "polarizing."

"There are some folks who benefit from divisive elections and the status quo," Deb Otis, a senior research analyst for FairVote, tells Reason. "Reforms will always have pockets of opposition."

And just because Republicans are behind the bans in Florida and Tennessee doesn't mean they're the only ones against ranked-choice. In New York City, establishment Democrats attempted to halt the implementation of ranked-choice voting in the mayor's race just last year. They failed, and Eric Adams eventually won with a majority of the vote after several rounds of tallies. Adams himself had spoken out against ranked-choice, claiming it would disenfranchise minority voters, even though the voters themselves (as in Sarasota and Memphis) overwhelmingly approved a referendum on it.

Despite the recent setbacks in Florida and Tennessee, Otis and FairVote are keeping a positive outlook and promoting the growth of adoptions of ranked-choice voting elsewhere. Maine pioneered ranked-choice voting in the U.S. for several state-level races (including governor and lawmakers), and a new bill will allow cities and towns to use the system for local races. In Utah, a Republican-sponsored bill signed into law by a Republican governor provided some technical tweak to its pilot program as ranked-choice voting continues to grow there. And Alaska will be using ranked-choice voting to replace Republican Rep. Don Young, who died in March.

"More and more cities are using ranked-choice voting," Otis says. "We continue to see voters like ranked-choice voting, understand it, and continue to elect candidates who have broad support."

Show Comments (97)