Colorado Legislators Advance Bill To Ban Police from Lying to Minors During Interrogations

Reason reported last year on how minors are particularly susceptible to being coerced into false confessions.

Democratic lawmakers in Colorado are advancing a bill that would ban police from lying to minors during interrogations, a practice that innocence groups say contributes to false confessions.

The Denver Post reports that the Democrat-controlled Colorado Senate passed S.B. 22-23 by a party-line vote last week, sending it to the state House. The bill would prohibit police officers from using deception during interrogations of juveniles. It would also require law enforcement to electronically record all juvenile interrogations, and it would make any statements obtained by deception during an interrogation inadmissible in court against the juvenile, unless the prosecution can prove the statement was voluntary.

Reason reported last year on how states are finally starting to limit deception against minors during police interviews after years of mounting evidence that youths are particularly susceptible to being coerced into false confessions. In 2021, Illinois became the first state in the U.S. to ban police from lying to minors during interrogations. Oregon followed suit shortly after, and Washington passed a law requiring attorney consultations for minors before interrogations.

However, Colorado Republicans and state law enforcement oppose the legislation, insisting deception is a necessary tactic to solve crimes, and that the proposed reforms are "pro-criminal" (presumption of innocence be damned). The Denver Post reports that opposition to the bill rests "largely on the ideas that it's not needed, as parents already have the right to accompany kids in interrogation rooms, and both parents and kids in those situations must be read Miranda rights. Opponents note that judges already have discretion to toss statements or confessions obtained through trickery, if they're so inclined. They point to the lack of available data to bolster the Democrats' case. And they argue that deception is sometimes an important and useful tool that should not be outright banned."

These facile arguments pretend that safeguards that we already know have failed to stop false confessions will be enough to stop future instances. According to the Innocence Project, nearly 30 percent of DNA exonerations involved false confessions. Roughly a third of those false confessors were 18 years old or younger at the time of their arrest.

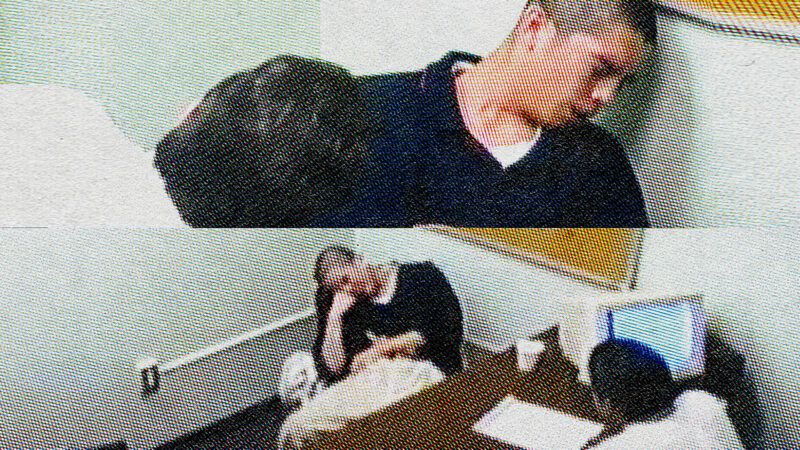

Take, for instance, the case of Lawrence Montoya, who Reason profiled in its story on coerced confessions last year. In 2000, Denver police brought Montoya, then 14 years old, and his mother into the station to question Montoya about the murder of a local woman.

Montoya admitted that he'd unwittingly taken a joyride with his cousin in the woman's stolen car the day after her death, but he denied ever being at the scene of the killing. Montoya's mother encouraged him to talk to the police and tell them everything he knew, and she eventually left the room, allowing detectives to lean on Montoya harder.

The detectives claimed they found his shoeprint in the woman's blood, among other evidence. "If you were there, you better give it up," a detective told Montoya. "We've got fingerprints, we've got blood prints, we've got saliva prints," one said. "We've got everything."

"You don't have a fuckin' clue what we can prove," the other detective added. "Your ass is hanging out big time."

Montoya, sobbing at times, denied being at the murder scene 65 times, but after several hours of badgering and threats of damning physical evidence against him, the teenager admitted to being at the woman's house the night of the murder. He spun a story about the night using the facts detectives had been feeding him, and the detectives helpfully corrected him when he got major details wrong.

Despite no physical evidence linking him to the crime (the officers' claims were nothing but bluster), a jury convicted Montoya of first-degree felony murder. He spent 13 years behind bars before prosecutors cut a deal to release him on time served in exchange for his pleading guilty to being an accessory after the fact. Montoya filed a still-ongoing federal lawsuit against the city of Denver and several Denver police officers in 2016.

The Denver Post recounts the story of another child who was pressured by police to falsely accuse her parents of sexual assault. When the police in Wenatchee, Washington, brought 11-year-old Amber Doggett in for questioning in 1993, they were already convinced that a sexual assault ring existed in their town—a fantasy that occupied the vivid imaginations of many police departments in the 1980s and 1990s and led to many wrongful convictions. So when Doggett denied ever being abused, the police insisted she'd been brainwashed and told her that her three siblings had already confirmed the abuse to them, which was a lie. Eventually Doggett broke down and told the police what they wanted to hear.

"What the (expletive) was I supposed to do? I was 11 years old," Doggett told The Denver Post (bowdlerization in the original story). "It was nighttime, I couldn't just walk out of the police station alone. I was in a situation where everything was just so terrifying. My brain switched to survival mode."

Doggett was then forced to undergo a sexual assault examination, and the police told her that it showed proof of abuse, which was, again, a lie. The Denver Post continues the story:

The consequences of the sham stretched for many years. Doggett was placed in foster care and her parents were arrested, convicted and sent to prison. She grew depressed and fell behind in school. She lost her appetite and started to self-harm, and was eventually institutionalized and heavily medicated. She had a hard time trusting adults.

Her parents were ultimately cleared of all charges and the fictitious Wenatchee sex abuse ring was long ago debunked.

This is apparently the sort of ace detective work that Colorado Republicans and law enforcement think should be preserved.

Show Comments (40)